Due to months of military clampdowns and coronavirus lockdowns, there’s no shortage of material for the political cartoonists documenting Kahsmir’s unrest and its humanitarian fallout, even as press freedom shrinks.

In August 2019, India’s government stripped the former state of Jammu and Kashmir of its semi-autonomous status. Prime Minister Narendra Modi said the move was aimed at ending separatism, but it escalated tensions in a region that has weathered years of conflict, protests, and crackdowns on an anti-government insurgency.

The ensuing months have seen extended curfews, disruptions to schooling, a crumbling economy, continuing restrictions on high-speed mobile internet, surging border tensions with China in nearby Ladakh, and a health system struggling to contain the pandemic.

Today, the cartoonists believe they’re taking greater risks than ever.

Anis Wani, a 23-year-old cartoonist who works for The Kashmir Walla, a Srinagar-based outlet, said he received anonymous death threats by phone after he posted his first post-crackdown piece on India’s independence day, last 15 August. The cartoon shows a Kashmiri man, his lips sealed, tied to a pole flying the Indian flag – a commentary contrasting India’s national celebrations with Kashmir’s restrictions.

“I continued my work despite this threat,” Wani said. “I was scared but I continued making cartoons.”

Kashmir has a rich, multilingual press, but journalists say self-censorship in local papers is on the rise, driven by intimidation, denial of local government advertising, and the threat of arrest. Several journalists have been arrested or investigated under anti-terror laws this year, and a controversial new media law targeting “fake news” gives the government more power to censure independent reporting, critics say.

Political cartoonists say they feel added pressure due to their visual medium, which combines art with overt commentary.

“You can write about or against a certain event or a person,” said Suhail Naqshbandi, a prominent cartoonist published in local newspapers and online. “But putting the same commentary in a drawing draws a different reaction and it’s more potent as it spreads fasters and catches more eyes.”

Heeba Din, who has a Ph.D researching political cartooning from the University of Kashmir and specialises in visual narratives and political communication, said cartoonists have become central to public discourse.

“While historians might contest the factual nature of cartoons, none can deny the ability of the cartoons to tap into the public memory and establish narratives,” she said.

Documenting Kashmir’s crackdowns

Despite the uncertain environment, Kashmir’s political cartoonists continue to use their medium to critique public policies and spotlight problems.

One frequent subject is India’s ongoing restrictions on high-speed mobile internet in Kashmir, which doctors say has also impeded the COVID-19 health response.

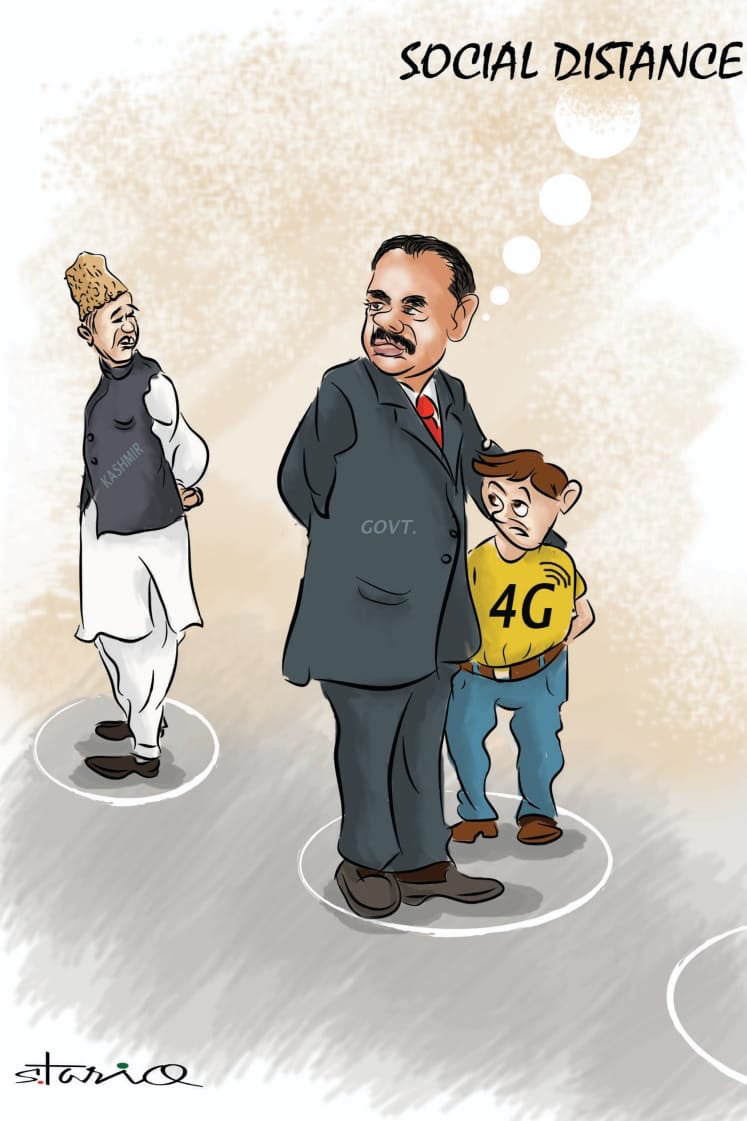

In an image published in March, S. Tariq, a cartoonist from southern Kashmir whose work regularly runs in the English-language daily Kashmir Images, compared the communications blockade to coronavirus public health measures.

His cartoon, titled “social distance”, shows a government official enforcing the gulf between Kashmir and the internet, both symbolised as people. It represents “the unlawful distancing the government has kept between a common man and 4G internet service,” Tariq said.

Rafia Rasool – the sole woman out of roughly half a dozen regular political cartoonists in Kashmir – publishes in the Urdu-language The Daily Aftab.

“In Kashmir, I believe there are very few female journalists and cartoonists who prefer journalism as a good, long-term career option,” Rasool said. “They are a little apprehensive that being a female, they won't get a job in this field.”

Her images often take aim at the social impacts of Kashmir’s crackdowns. One shows a book bag covered with cobwebs: Schools have been largely closed for more than a year – starting from the August 2019 clampdown and continuing through this year’s pandemic.

Another image, of an apple personified as a sickly hospital patient, illustrates the economic fallout from successive lockdowns: the lifeblood fruit industry suffered heavy losses starting with the 2019 shutdowns.

As with his “independence day” cartoon, Wani’s work often juxtaposes outsider perceptions of Kashmir with what he sees in daily life.

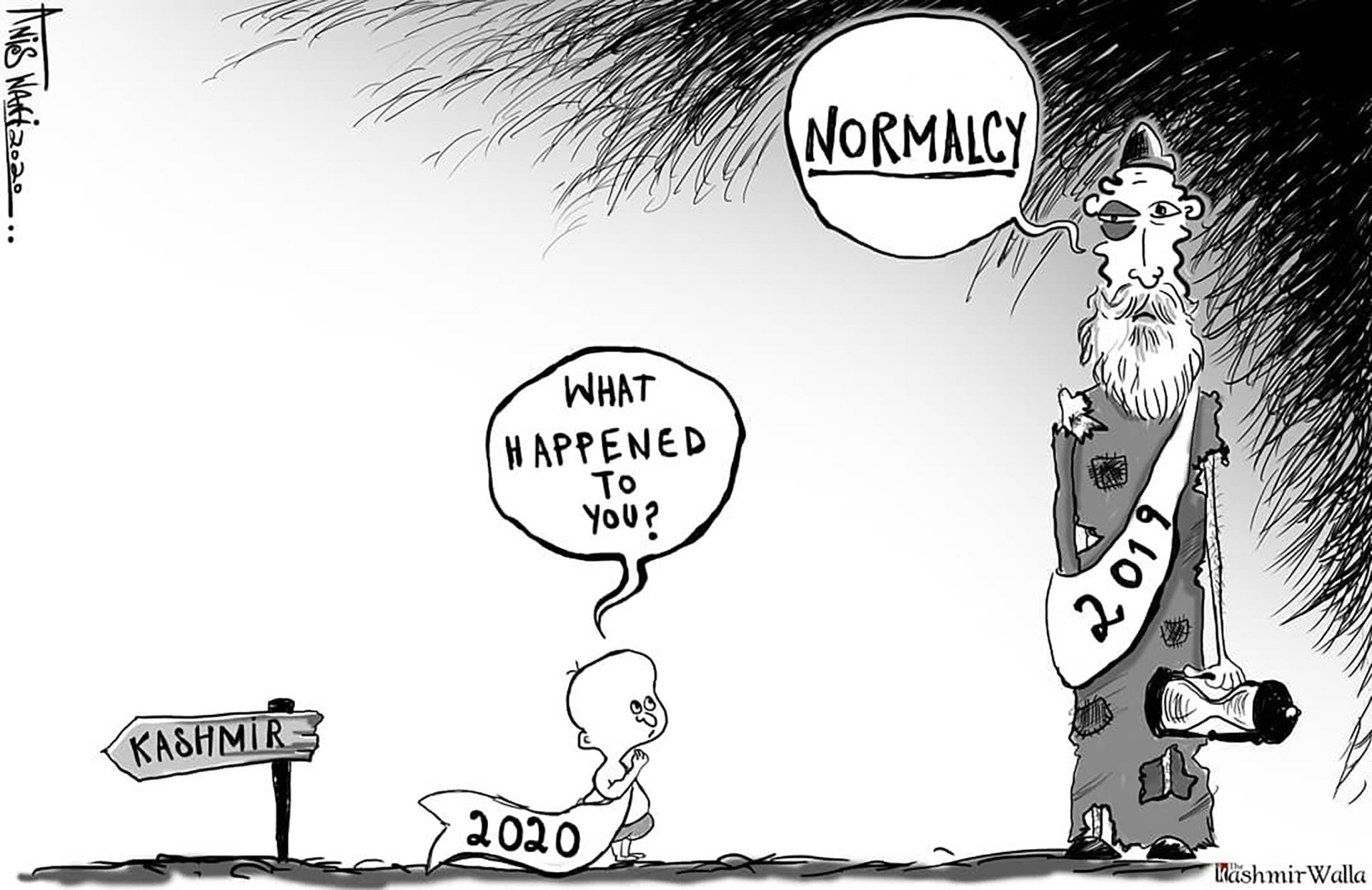

In a piece published in January, Wani took aim at the term “normalcy”, which Indian politicians and national media outlets frequently used to describe Kashmir weeks after the August 2019 clampdown, implying that the disruptions were over.

In reality, a heavy military footprint, curfews, and communications blockades continued long after: “Things were very different on the ground,” Wani said.

A pencil under siege

While frequent monitoring and pressure to self-censor are a fact of life for many of Kashmir’s political cartoonists, lockdowns and blockades are a physical barrier to their work.

Most local newspapers couldn’t publish for two weeks after the August 2019 military clampdown began. Early on, some journalists had to smuggle out their work on USB drives after authorities severed phone and internet access. For weeks, journalists shared a sole cable internet connection in a government-run media room in Srinagar.

Wani was one of the first cartoonists to publish online after the clampdown, as he was in India’s capital, New Delhi, when it began.

Strict curfews, restrictions on movement, and the internet blockade prevented Tariq from publishing for nearly two months. “It felt as if everything was taken away from us,” he recalled. “There was this deep feeling of insult and sudden loss.”

Disconnected from the outside world, Naqshbandi was unable to finish a single cartoon for months – thwarted at first by the restrictions, then overwhelmed by the mental toll of what was happening around him.

In need of an outlet to vent his frustrations, Naqshbandi published his post-crackdown cartoon after nearly six months. It showed a pencil with a broken nib, wrapped in coils of concertina wire, which have become a common sight at Kashmir’s ubiquitous roadblocks and checkpoints.

“The cartoon shows a pencil under siege,” he said. “It symbolises restrictions on freedom of expression and also state censorship on freedom of press.”

mm/il/ag