In 1984, a year after taking charge of the former French colony known as Upper Volta, the late revolutionary Thomas Sankara renamed the country Burkina Faso – the land of upright and honest men in local parlance.

The country’s long history of religious tolerance and social harmony – in a region troubled by conflict – made it a fitting name, even after the death of Sankara in a 1987 putsch led by his close aide, Blaise Compaoré.

But in recent years the land of honest men has found itself facing an existential threat: spreading violence by Islamist militants and a patchwork of other militia groups that is destroying the social fabric and turning communities against each other.

Out of the world’s 15 deadliest conflicts tracked last year by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Burkina Faso was the country that worsened the most. With nearly 840,000 people now internally displaced, according to the UN, and more than two million in need of aid, things are going from bad to worse.

The New Humanitarian has been on the ground covering the latest violence. The numbers only tell part of the story of a conflict that has touched all aspects of life. Here, we share the views of six lesser-heard Burkinabé voices – a civil society leader, an aid worker, an imam, a teacher, a journalist, and a researcher.

Chrysogone Zougmoré, civil society: ‘Stigmatisation sews germs of civil war’

Chrysogone Zougmoré, president of the Burkinabé Movement for Human Rights, has worked for rights organisations for more than 30 years, and seen his fair share of abuses, particularly under Compaoré. But the constant flow of civilian killings in recent months – by jihadists, local self-defence groups, and the government’s own security forces – is worse than anything he’s seen before.

“The situation is concerning and alarming, and the consequence is that soldiers and civilians are being killed and there are many internally displaced people living in very hard situations,” he said.

Read more → How jihadists are fuelling inter-communal conflict in Burkina Faso

Insecurity is also impacting a once thriving civic space. After Zougmoré’s organisation published a report last year denouncing extrajudicial killings by the military, it was threatened by government supporters on social media.

Zougmoré thinks rights organisations in Burkina Faso and neighbouring countries affected by extremism should come together to create the civil society equivalent of the G5 Sahel – a regional military force created to combat extremists. A proposal is currently in the works.

He’s also hatching a plan to prevent the stigmatisation of ethnic groups such as Fulani herders – accused of joining and harbouring extremists – and promote peaceful coexistence between communities.

“Physical and verbal aggression and stigmatisation sews germs of civil war,” Zougmoré said.

Simon Nacoulma, aid worker: ‘They don’t understand what’s happening to their country’

The founder of a local aid group called Community Initiative for Changing Lives, Simon Nacoulma thinks the key to maintaining social cohesion is making an example of places where violence is most common.

“I ask them if they want what happened to the people in the Sahel (a northern province that has seen a lot of extremist violence) to happen to them,” he said.

Founded in 2002, his aid group supports vulnerable communities across the country with agricultural projects that help them grow fruit and vegetables, and monthly talks about the importance of social cohesion.

As the crisis deepens, Nacoulma said the conversations have revealed increasing community divides – including between Muslims and Christians – and shown just how fearful residents are about the way the country is changing.

“There is violence that they never experienced, and they don’t understand what’s happening,” he said.

Resolving differences through traditional dialogue mechanisms can help communities stick together during turbulent times, as does local leaders reminding people of the strong social ties stretching back generations, Nacoulma added.

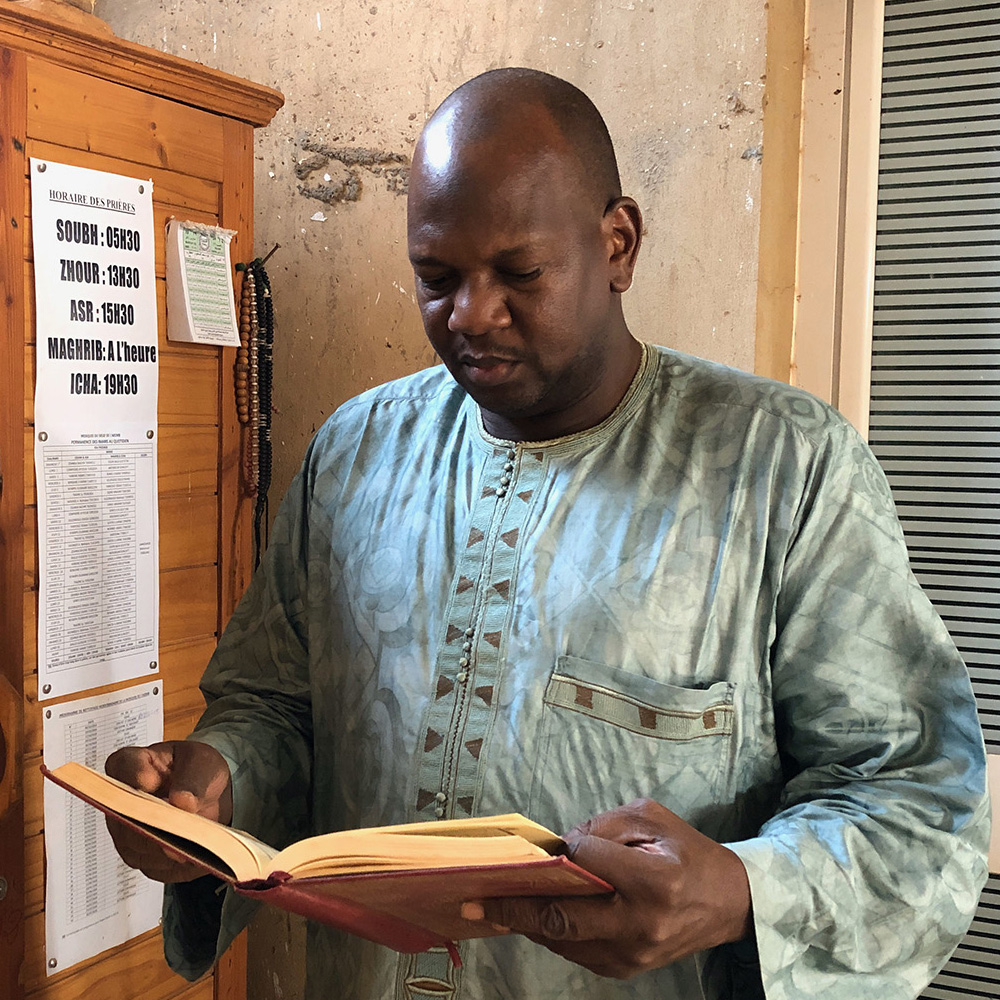

Tiégo Tiemtoré, imam: ‘If a boat sinks, everyone sinks together’

A series of recent attacks by jihadists on churches in Burkina Faso has triggered fears of religious strife in the country. But Tiégo Tiemtoré, an imam in Ouagadougou, thinks the violence has actually increased solidarity between religious groups.

“It’s like a boat – if it sinks, everyone sinks together,” he said, explaining that people stick together because they realise everyone suffers when they don’t.

Tiemtoré credits the Brotherly Union of Believers, a well-known organisation based in the northern province of Seno*, for travelling to mosques and churches preaching messages of peace and tolerance.

“Religious groups bring people hope and they encourage people to keep moving forward,” Tiemtoré said.

Read more → In Burkina Faso, arming civilians to fight jihadists. What could go wrong?

While the imam doesn’t have a solution for ending the crisis, he thinks the government should work more closely with neighbouring countries and be open to negotiating with extremist groups – an approach being trialled in neighbouring Mali.

“At the beginning, I was against negotiating with extremists,” Tiemtoré said. “But seeing the situation on the ground, if the military can't control it, we can try other possibilities.”

Fidèle Tiono, teacher: ‘We call them terrorists because we live in terror’

Insecurity has forced more than 2,500 schools to close across the country, impacting more than 330,000 students and 11,000 teachers.

Thirty-two-year-old English teacher Fidèle Tiono is one of them. Since he was forced to flee his village of Nagbingou in the country’s Center North province in February, he’s had nothing to do.

“I suffer from idleness,” Tiono said of his new life in Ouagadougou.

Relatively new to the teaching profession, Tiono is keen to get back to work. A month after fleeing his village, he and several other teachers even travelled back to Nagbingou, only to find everyone else fleeing in the opposite direction.

When schools are operational, teachers and students aren’t at ease, Tiono added. Every time a motorbike – the preferred mode of transport for armed groups – passes by, students will look worriedly out of the window.

“We call them terrorists because we live in terror,” Tiono said. “Teaching requires a peaceful environment.”

Guézouma Sanogo, journalist: ‘Many don’t want to work anymore because of fear’

In a complex conflict with multiple sides, everyone depends on accurate information. But for Guézouma Sanogo, president of Burkina Faso’s national journalist’s association, the country’s “chaotic” situation is negatively impacting press freedom.

Burkina Faso’s penal code was changed last June so anyone who publishes information or images from a crime scene of a “terrorist nature” without permission can be charged, with punishments of up to five years in prison and a maximum fine of around $17,000.

The revised law isn’t intended to restrict press freedom but to protect the dignity of soldiers and civilians who have been killed, government spokesperson Rémis Fulgance Dandjinou told TNH.

But the law has resulted in journalists largely not reporting attacks for fear of reprisal, Sanogo said, while extremists have also threatened reporters who cover issues such as forced marriage, female genital mutilation, and the importance of educating girls.

“Journalists are under a lot of pressure,” said Sanogo. “Many don’t want to work anymore because of fear.”

Cheickna Yaranangoré, researcher: ‘The mentality of society is changing’

For the past three years – thanks to a grant from the Canada-based International Development Research Centre – Cheickna Yaranangoré has been studying how youth in Burkina Faso resist being drawn into violence.

He believes that what used to be a strong Burkinabé national identity – one that wasn’t based on ethnic or religious difference – is weakening due to conflict, inequality, a lack of social services, and deep-rooted social grievances.

“The mentality of society is changing,” said Yaranangoré.

During the next few months, the research team will be travelling across Burkina Faso to speak with local authorities, village leaders, and civilians about the importance of building community harmony, avoiding misinformation, and stopping prejudice.

“There’s a global message that everything is falling down here, but it’s not true,” Yaranangoré said. “Crisis is an opportunity for the country to build (itself) up.”

*(An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the Brotherly Union of Believers is based in the northern province of Soum)

sm/pk/ag