South Sudan is experiencing its worst food crisis since independence as seasonal flooding sets in amid an economic downturn and renewed conflict that has spiked despite a peace agreement and the formation of a unity government.

Efforts to distribute food have been complicated by funding gaps in the humanitarian response, and by the repeated looting of food convoys and warehouses. Attacks against aid workers have also risen, and government officials have created new administrative hurdles for some agencies.

“At a high level of government, the peace dividend is being enjoyed, but in the communities, people are more frustrated than ever,” said Abraham Kuol Nyoun, a political scientist at the University of Juba in South Sudan. “This peace, as it is, cannot put food on the table.”

Some 7.2 million people are currently enduring severe hunger across South Sudan – the highest number since the country of roughly 12 million broke from Sudan in 2011. Of those, tens of thousands are thought to be in famine. The government has downplayed the crisis.

Though humanitarian agencies have managed to reach most of those in greatest need this year, aid officials said efforts to raise the alarm at an international level have failed to garner extra resources, leading to ration cuts for those displaced people and refugees who are considered less needy.

“[We tried to] say that this is a significant deterioration, [but] the advocacy hasn’t hit home on the international stage,” said a Juba-based senior aid official who asked not to be named given how sensitive the issue is with the government. “There is a feeling outside of South Sudan that the country is always bad.”

Some had hoped the humanitarian situation would improve when President Salva Kiir formed a unity government last year with opposition leader Riek Machar – now the vice-president – following a power-sharing deal signed in September 2018.

“I have grown crops, but I can’t even go and weed them because I fear being killed.”

That agreement was the second between Kiir and Machar since a civil war broke out in 2013, costing 400,000 lives and displacing millions of people in the world’s newest country.

While the two men have stopped open political fighting, key parts of the deal have not been implemented, and violence – much of it connected to political and military elites in Juba – has escalated, heightening the food crisis and complicating relief efforts.

As local officials have been appointed by the new government, aid agencies have also faced increased administrative impediments, which were already common in South Sudan. “We are spending half our time dealing with requests and permissions,” said the senior aid official, who also mentioned ad hoc fees being levied to register projects. “It’s happening across the country.”

Spreading conflict and disrupted livelihoods

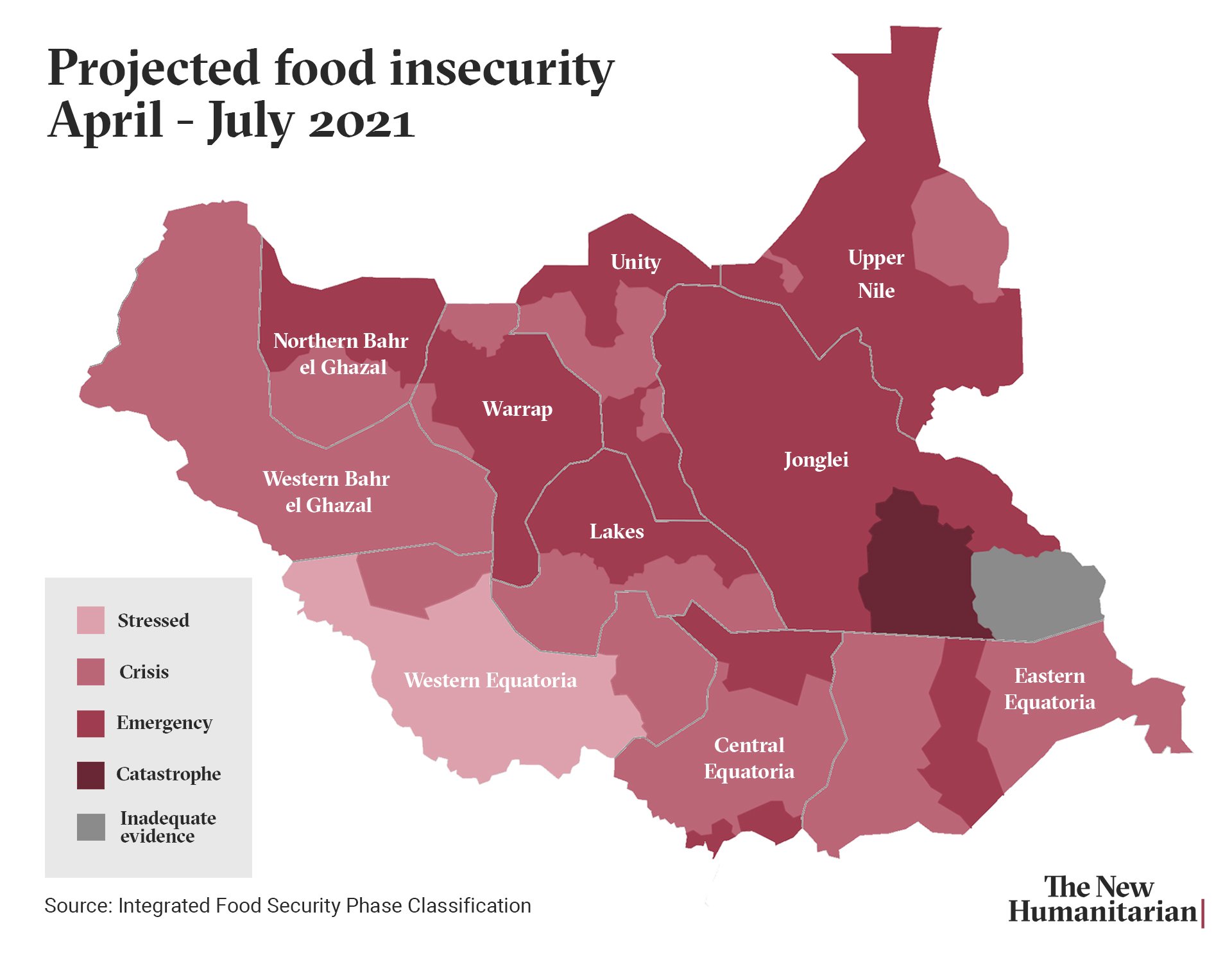

South Sudan often experiences high levels of food insecurity, which peak in severity between May and July during the lean season, when families have depleted most of their harvest and are highly dependent on food assistance, which is almost entirely provided by aid agencies.

Since 2015, there have been 37 pockets of famine detected in the country, one famine declaration, and a recent “famine likely” announcement – issued because mortality data was lacking but the available information pointed towards famine.

This year’s hunger crisis has several causes. Flooding, which affected over a million people in 2020, has eroded coping mechanisms and proved hard to recover from. Further rains have fallen in recent weeks, impacting some 90,000 people.

“Floods have [destroyed] all my sorghum and there will be nothing for me and the children for a very long time,” farmer Deng Aleng told The New Humanitarian earlier this month from the northern administrative area of Ruweng.

Financial problems – exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic – have made matters worse. South Sudan’s economy is expected to contract by 4.1 percent in 2021, according to the World Bank, while currency depreciation and soaring food prices have eroded people’s purchasing power.

Violence – the main cause of famine conditions since 2015 – has also continued at a level some experts say resembles a full-scale national armed conflict. Tens of thousands of people have been displaced, farming has been disrupted, and the mobility of pastoralists restricted.

South Sudan is also one of the most dangerous countries in the world for those trying to help – 17 aid workers have been killed since January, according to the Aid Worker Security Database.

“Life this year is worse [than before],” Abuk Kat, a mother of six from the conflict-affected eastern town of Pibor told The New Humanitarian in a phone interview. “I have grown crops, but I can’t even go and weed them because I fear being killed.”

Though current violence is framed by the government and some humanitarian agencies as “inter-communal”, experts say it is often closely connected to national political and military dynamics, indicating Juba’s lack of interest in alleviating food insecurity.

“It is absolutely within the power of this government to create a food secure environment for its population,” said a second humanitarian official who asked not to be named to avoid reprisals from the authorities. “It is a question of political will.”

While ostensibly committed to the unity government, analysts and UN reports say Kiir’s allies have worked to keep the opposition SPLA-IO weak by encouraging high-profile defections and then using the defectors militarily against other opposition forces.

And, in other cases, political and military elites have provided material support to community militias as part of a broader struggle between individuals seeking power and leverage within the country’s new political settlement.

Fighting between community militias creates especially high levels of food insecurity because of their social and geographical closeness to one another, explained an aid worker with significant experience working on food insecurity in South Sudan.

“They know how to target one another where it hurts,” said the aid worker, who asked not to be named, citing the sensitivity of the issue. “They know where the cattle are being kept. They know where the grain is being stored. The closer the social units that are in conflict with one another, the bigger the [impact] on food insecurity.”

The nature of the fighting forces has complicated access to communities in need. During the civil war, agencies reached areas by speaking to familiar armed groups with clear command structures. With the current community militias, “it is often unclear how to operate… and with whom we are negotiating”, said the aid worker.

Some fear conflict could soon get worse. In-fighting this month between rival members of the SPLA-IO has led to clashes in parts of the country and reflects growing tensions over Machar’s leadership.

And military operations against the holdout rebel National Salvation Front have also been taking place in the southern Equatoria regions, an area traditionally seen as the country’s breadbasket.

Stolen supplies and funding fears

Agencies have conducted advocacy campaigns explaining that this year’s hunger “is significantly worse than what we have seen in recent years”, but the message hasn't really resonated outside the country, the senior aid official told The New Humanitarian.

“The UK’s famine envoy, Nick Dyer, came [to South Sudan], the Emergency Directors Group did a special meeting,” the official said. “But how much that relates to extra cash, aid, and extra support, is questionable.”

Though a UN-coordinated humanitarian response plan requested $1.68 billion for 2021, it is currently just over 50 percent supported. Funding for food security and livelihoods is just 35 percent covered. Underfunded response plans are common in crises around the world.

“We call them criminals, but it is hunger that made them loot. One cannot allow himself to die while sorghum is being carried in front of him.”

The current gap means food aid has been prioritised to those facing the highest levels of hunger at the expense of other food insecure populations. Little money and resources are, meanwhile, available should mass-scale flooding take place in the coming months.

Theft of food aid on a scale some say is higher than previous years has further hindered operations. Opportunistic groups have been blamed for some incidents, while warring communities have also used looting to prevent aid from getting to one another.

In one of the latest incidents, on 15 July, a WFP convoy carrying food supplies to the conflict-affected state of Warrap was ambushed as it got stuck in the mud, according to the UN’s World Food Programme, or WFP.

Mawien Majith, a government official from the area where the convoy was attacked, said the looters included women and children among “hundreds of armed youth”.

“We call them criminals, but it is hunger that made them loot,” Majith told The New Humanitarian. “One cannot allow himself to die while sorghum is being carried in front of him.”

Adeyinka Badejo, deputy country director for WFP in South Sudan, added: “We are already facing a situation where we have reduced funding… and then we have a situation where opportunistic raiders are looting the food in the warehouses or in transit.”

Meanwhile, people in some communities have been protesting against aid agency hiring practices, arguing that they should employ more staff members from their local area, rather than from distant parts of the country.

According to WFP, the protests – which have taken place in previous years too – reflect “a growing frustration among youth regarding high unemployment and the lack of income opportunities” in the country.

Nyoun of the University of Juba added: “The youth who were participating in the war are back in the communities, with no [peace] dividend. To survive, they are engaging in communal conflicts, looting, and plundering, because they have no other livelihood.”

Philip Kleinfeld reported from Bamako. Edited by Andrew Gully.