The humanitarian sector has a trust problem. This is an existential issue that needs immediate attention because trust will make or break a humanitarian response. Trust – or lack there-of – has very real implications on humanitarian action.

The humanitarian response in Syria exemplifies many of the challenges the sector faces when it comes to trust. I visited Syria in 2012, in the early days of the war. At that time, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) had been thrust into a central coordination role that it was neither accustomed to, nor particularly wanted.

Within the western-led multilateral humanitarian system, SARC was initially seen as an auxiliary of the government and heavily mistrusted to provide neutral, impartial aid in a conflict zone. Donors were reluctant to fund SARC while international aid agencies hesitated to work with the body.

But like all national societies, SARC comprises local volunteers, some from areas that had rebelled against the government, which has led to mistrust from the government itself. Several SARC volunteers and staff were accused of sending aid to rebels, detained, and, reportedly, even tortured.

SARC found itself squeezed by both sides, but the organisation has worked hard to earn trust and now distributes 80% of aid in Syria, including across conflict lines.

But it wasn’t just SARC that had problems. There was mistrust – in some cases well-founded – at many levels.

Civil society distrusted the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) for its perceived inaction, as well as the UN, seen to be too close to the government.

And yet, there was deep distrust between the Syrian government and the UN, part of a wider mistrust of foreign aid by the Syrian government and its allies.

UN agencies were competing against each other to get on the “good side” of the government for access.

There was distrust even between humanitarians on the ground and the political arm of the UN, because of a feeling that humanitarian action had been instrumentalised and used as a fig-leaf for political inaction.

Of course, trust wasn’t the only issue. There’s a whole other level of dynamics with realpolitik, misinformation, propaganda, manipulation and instrumentalisation at play.

But at the level of the humanitarian response, this polarising situation, with mistrust on all sides, had serious implications: visas refused, permits to move denied, attacks on aid convoys – even after negotiations to secure safe access. Ultimately, we’re talking about lives lost.

A 2016 review (PDF) of the humanitarian response in Syria found that "the Syria case has highlighted the inherent and, at times fatal, flaws of the humanitarian system, which had largely failed in Syria.”

Trust across the sector

The New Humanitarian is the only news organisation dedicated to reporting about humanitarian needs and response around the world – from conflict to disasters, refugee flows to health emergencies. We document the results of successes – but more often breakdowns – in trust everyday. Thus our reporting can help illuminate what’s at stake when we talk about trust.

A clear example can be seen in the Ebola response in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In July, our journalist, Emmanuel Freudenthal, traveled to an Ebola cemetery in Beni, where he took this photo. You can see a soldier surveilling the response activities. There, Emmanuel met a man named Bienvenue Tsimbula.

Bienvenue had been heading to a healthcare site to be vaccinated against the virus. He found a group of local protesters asking the medical team to leave, frustrated by family members’ bodies being transferred against their will and safe burials being imposed by force. The health workers were escorted by Congolese police officers.

Locals threw stones; officers responded with live bullets.

Bienvenue was just a bystander, but ended up shot in the spleen and had to have surgery. His injuries left him unable to farm his fields.

Some 2,210 people have died from contracting Ebola in this outbreak. Another 11 have died in 390 attacks on health facilities and associated violence.

For Bienvenue, trust was compromised by what the UN has described as a “disproportionate use of force” by police and army personnel dealing with protests against Ebola responders.

This rush to securitisation has directly undermined the ability to build trust. One activist who witnessed the attack told our journalist, “The youths were thinking, ‘Those people, working for the response, are killing us... we too have to kill them.’”

Clearly, something has gone deeply wrong when recipients of aid feel they are at war with those trying to help them.

The story of this shooting is the story of decades of mistrust of responders by communities frustrated by years of marginalisation, neglect and perceptions of self-interest, as they watched money being pumped into the Ebola response, while other serious challenges in Congo were left ignored.

But there’s also mistrust of communities by responders. Aid organisations often think they know best and often don’t trust communities to make decisions about how to treat their dead and how to live their lives.

This was the case in the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Aid organisations sometimes saw the local people as “irrational, fearful, violent and primitive: as too ignorant to change”.

Lack of trust in the Ebola response on both sides has contributed to aid workers killed, people refusing to take the vaccine, and the deadly virus continuing to spread to this day.

Finding a route to trust

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

For instance, rather than force families of Ebola victims into safe burials, Doctors Without Borders says it gave families the choice — and 100% of the time they chose a safe and secure burial. They just wanted the agency to be able to do it.

Earlier this year, we published an article by Dr. Jean-Christophe Shako, then the Ebola response coordinator in Butembo.

He had heard that the body of an eight-month-old boy who died from Ebola was in a village controlled by the Mai-Mai, self-defence militias often feared by the local population because of years of crimes, including torture, kidnapping, and indiscriminate killings.

The risk of Ebola spreading is most severe immediately after a patient dies, so Dr. Shako knew he needed to get the village to vaccinate people as soon as possible.

The Mai-Mai are known to be well armed and unafraid of the authorities. Even the national police and army don’t dare venture into some rebel-controlled zones.

People thought he was crazy.

When he got to the village, he asked to see the chief. He found him about to have lunch. They invited him to join them at the table.

The mood was tense and his hosts remained silent, observing his behaviour. Only when he began eating did the atmosphere lighten. The village chief started smiling and talking. He appreciated the humility Dr. Shako had shown by agreeing to eat with them.

As it turns out, they had never heard of Ebola nor of vaccination. Dr. Shako spent 30 minutes explaining the virus to them, how it spreads, the preventative measures possible, and how the vaccination works.

Without saying a word, the village chief went outside, gathered the villagers and handed over a list of all those who had been in contact with the baby boy so that responders could follow the chain of transmission.

Seventy-five people came forward. The vaccination teams did their work. Not a single person in that village developed the virus.

Trust between aid agencies and communities opens up access and ultimately saves lives. We’ve seen this time and time again in stories we have published about locally-led humanitarian action.

In the flood response in Malawi, in the fight to build peace among pastoralist communities jostling over dwindling resources in Kenya, in a drive for polio vaccinations in ISIS-controlled territory — local aid workers have been able to build trust with their communities succeeded where international aid agencies could not.

The movement promotes localisation through national societies, who often have greater access thanks to trust from their communities.

The counter-terrorism conundrum

Just as there are real consequences of trust between aid agencies and the communities they are trying to help, so too is that dynamic at play between agencies and governments.

States’ lack of trust in the systems and policies of aid agencies has led to aid being hampered by an increasing number of restrictions linked to counter-terrorism operations.

From Nigeria to Somalia to the US, counter-terrorism laws can make it difficult for aid workers to provide assistance to populations trapped in militant controlled areas. As a result, people in such areas are often left without any assistance at all.

But the consequences can be even more direct than that.

We all remember the attack by US forces on an MSF hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan in 2014. The attack went ahead despite the location being supplied to the US, who argued there were Taliban inside. Some 48 staff and patients died that day, some scorched to death in their hospital beds.

There were indeed Taliban inside, because, according to International Humanitarian Law, health workers have an obligation to treat injured combattants on both sides.

This was a breakdown of trust in humanitarians doing their jobs as mandated by international law and in humanitarians being truly neutral (the US argues it hit the wrong building by accident).

On the flip side, when humanitarians find the right balance between national security and humanitarian imperatives - and when trust exists – the situation looks very different. Think of the ICRC delegates who are granted access by authorities to detainees, even in places like Guantanamo Bay.

Trust in the system

A final word about trust at the systems level, rather than the operational level.

Lack of trust hampers progress on big reform packages like the Grand Bargain.

As we’ve reported, much of the Grand Bargain process has involved haggling over who will do what, with UN agencies waiting for donors to act, and vice versa. Neither side trusts that the other will do its fair share.

Humanitarians’ distrust of development actors has put plans for the nexus on hold, while distrust of the respective due diligence approaches of donors has made finding a common reporting framework more challenging.

Add to that disincentives for reform and competition between aid agencies, and three-and-a half-years after the Grand Bargain, progress in making aid more effective has been slow.

It goes without staying that the lack of public trust in the sector – fueled by sex abuse scandals, fraud and other abuses of power – poses an existential threat to its sustainability.

Building trust

So what can be done about this existential problem?

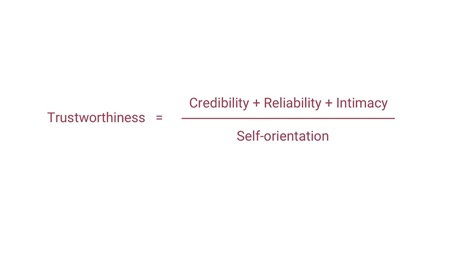

Here’s one definition of trust in academic literature:

In this equation:

- Credibility refers to the words. Is what you say credible? Are you a credible source?

- Reliability refers to the actions. Do you ‘say what you do and do what you say’?

- Intimacy refers to the safety or security that others feel when entrusting us with sometimes-sensitive information. Can you keep the information confidential?

- Self-orientation refers to the focus. Are you focused primarily on ourselves, or on the other person? Whose interests come first?

Trust is a consequence of good behaviour, not an ingredient, and while it takes decades to build and can vanish overnight, it’s not rocket science.

Here are four simple steps you can take at an individual, organisational or state level to build trust:

- 1. Don’t be a hypocrite

Be clear about your agenda.

Don’t say you abide by humanitarian principles and then join forces with the military or foreign governments.

Don’t call out war crimes by one state and not another.

Don’t say you stand for rights and then refuse to use the word Rohingya.

Don’t say you respect the independence of humanitarian action and then prosecute aid workers for doing their jobs.

- 2. Follow through on your promises

Do what you say. Say what you do. Be honest about what you can and can’t do.

Don’t respond in the crises that are easy and accessible and abandon those who need aid the most.

Don’t commit to localisation and then make excuses for why it’s not possible.

And certainly don’t come to Geneva, agree resolutions on the respect for International Humanitarian Law, and then go back to war to bomb hospitals.

- 3. Drink tea

Get to know the communities you serve. Drink tea with them. Learn about their culture. Speak their language.

Practice humility. The future of international solidarity is locals taking the lead with the international community supporting however the former would be most helpful.

- 4. Check yourself.

Trust is not a hotline. It's not about corruption, political influence, paternalism and hypocrisy. If you want to reduce your self-interest, you need to put a check on those human and organisational tendencies.

Trust should not be second-best to accountability. It’s not good enough to say, “Trust us”. Put in place the checks and balances that are visibly functioning and that give people a reason to trust you.

There have been steps in that direction, but there can always be more.

- What about addressing rivalries between the IFRC and the ICRC?

- What about encouraging the media like us to hold the sector accountable?

- What about free elections for the head of national societies?

- What about a freedom of information rule?

- What about having a beneficiary representative on your board?

Trust is not an auxiliary, it’s core to the mission. It’s time you started treating it that way.

This will require courage and leadership, and appealing to the better nature of your angels in difficult situations.

Are you brave enough?