On a July morning, a surly nurse jabs me in the arm with an experimental Ebola vaccine. It hurts.

Only after the liquid is inside my body does a doctor inform me, and the others who have been vaccinated – a mix of local residents and health workers – that we might experience side-effects.

Indeed I do. I spend a whole day in bed, and the morning of the next, writhing in pain. Some people are luckier, though, and have no side-effects.

The Merck vaccine I am given is still experimental – one of only two used in Congo, along with a second manufactured by Johnson & Johnson. Informed consent is part of the process that the World Health Organisation says must be followed for every patient. This is supposed to start with an explanation of the risks of the vaccine and then leave time for people to ask questions and, finally, to give consent.

But, before my vaccination, I receive no information on side-effects – or much else.

After I arrive, I give my name, which is passed along a chain of people. At the end of the chain, I am asked to sign a consent form, which I am told I can read later, on my own time.

“Here, we respect writing,” the health worker tells me as I rewrite my name on the form.

I have to practise shaping my letters until he is satisfied, a throwback to primary school. Once I get past the two “Ms” in my name, the worker tells me to remove the last letter.

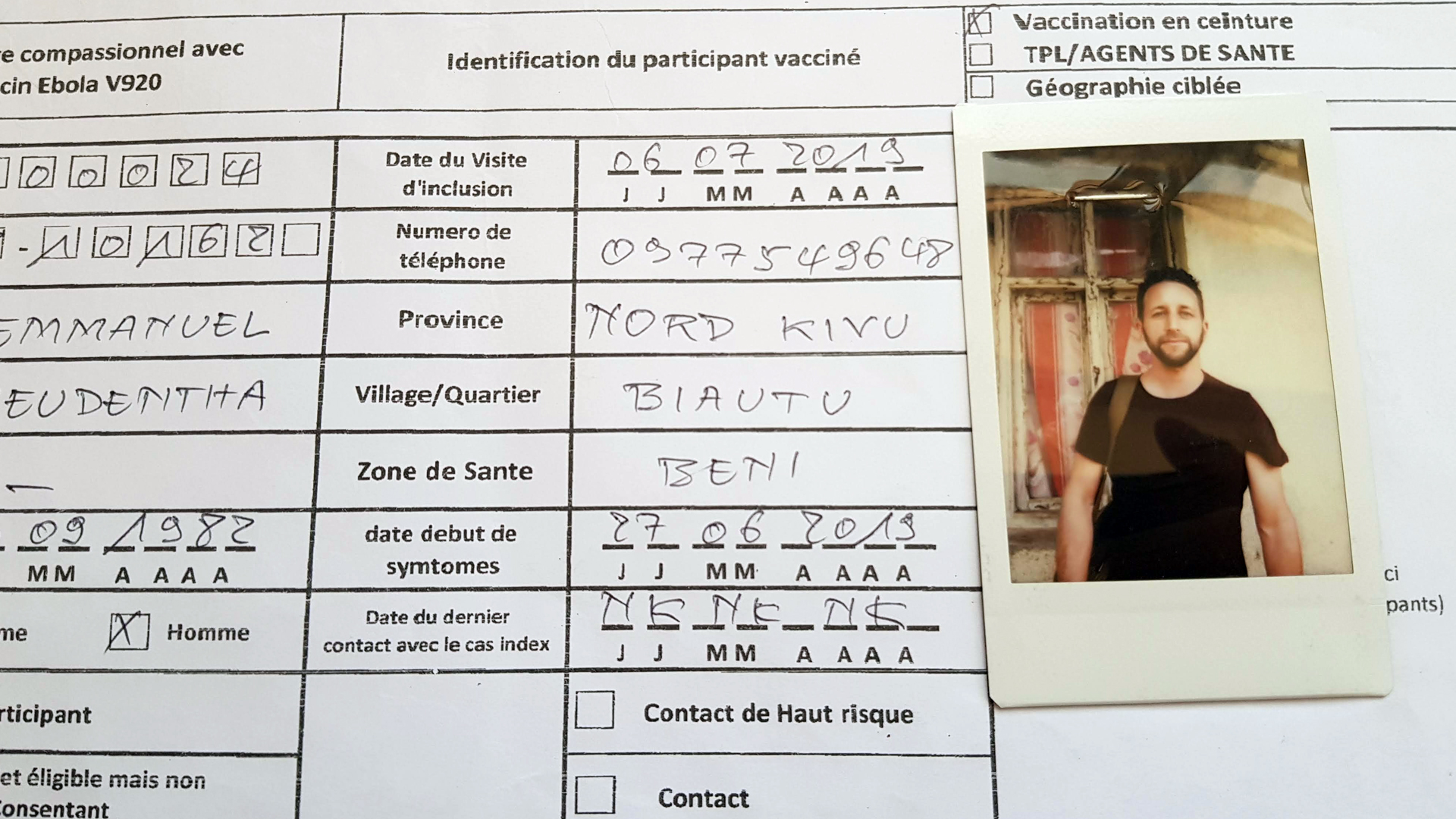

The form reads: EMMANUEL FREUDENTHA. Wherever the document is to be sent, there is no space for the last character. The long names common in this region are often truncated, I guess.

My photo is then taken with a polaroid camera and stapled to the form. I don’t feel as if I am contributing to research that may help stop the virus. I feel as if my body is a battleground.

“I wonder about the supply chain for the food I’m eating. How many hands have touched this banana? What about the bread?”

I imagine that’s how many of the Congolese who are vaccinated feel, though they suffer the additional intrusions of having their daily lives upended by the Ebola outbreak and the response efforts to keep it in check.

Still, I’m glad I have taken the vaccine, which, according to a month-long study, is nearly 100 percent effective after 10 days.

During those 10 days, while having breakfast in my hotel, I wonder about the supply chain for the food I’m eating. How many hands have touched this banana? What about the bread?

I am not yet aware that the hotel’s cook has Ebola and will die. I am still not sure if he prepared any of my meals after he got sick.

A lost convoy and a dead man’s details

Bothered by the vaccination process, I contact the WHO office in Geneva and ask for a written description of the consent process, without luck.

When the press officer calls me back, I explain that people are often vaccinated without consent – many had told me that. She replies that they must have misunderstood, that sometimes people in Congo don’t grasp the explanations.

There’s an awkward moment when I say I’m one of those people.

The WHO representative also explains that the organisation has implemented many of the things that “the community” asked for. Community acceptance has been characterised by the WHO and other groups involved in the response as the major hurdle to ending the epidemic.

That’s why I’m here, really: I’m hoping to see the Ebola response not from the perspective of the heroic doctors, or those who risk their lives to stop the disease. Many articles have, rightly, been written about them.

I want to see why “the community” is resisting their efforts, doubting their motivations. That means talking with the local citizens who bear the brunt of the epidemic. I know this increases the risk of contracting Ebola as well as being caught in or targeted by violence if I’m misidentified as a member of the Ebola response, but hopefully it’ll be worth it.

A few days later, I follow a WHO team in Beni while they perform another batch of vaccinations.

We’re a convoy of half a dozen SUVs, some with just two people inside, including the driver. We get lost.

Then we get to our destination, but it’s the wrong place. It’s not easy when there are no street names. After driving for a while along small roads, we finally reach the location where the vaccination drive is set to take place.

“In Ebola world you need to keep your distance and salute each other with awkward nods, elbow rubbing, and fist bumps of dubious protective value.”

The team members erect tents hastily, without acknowledging any of the bystanders who are watching quietly.

A few of the team members, who work with WHO or the Ministry of Health, loudly discuss the Ebola patient whose death led to this particular vaccination campaign – designed to protect people who knew him or others who may have come in contact with him. Anyone within a stone’s throw can hear the name of the patient, his job, and where he lived.

No handshakes, a lot of bleach

A few days previously, on my first day in Beni, I realised how Ebola can bring people apart. That day, I head straight to the headquarters of the Ebola response teams. As I extend my hand to greet Dr. Gaston Tshapenda, the coordinator in Beni whom everyone calls Dr. Gaston, he hesitates for a long second. Then he shakes my hand. That’s the moment I realise that this congenial gesture is no longer acceptable.

In Ebola world you need to keep your distance and salute each other with awkward nods, elbow rubbing, and fist bumps of dubious protective value. Handwashing with diluted bleach is mandatory each time you enter and exit a building, or at least the fancier ones.

Dr. Gaston is a friendly man who peppers his French with English, a second language he’s taught himself to an impressive level. He prints out a letter of introduction to show that I am authorised to report on Ebola here. But there’s been a mistake; it’s meant for another journalist.

The letter allows journalists to work for three or four days in Beni. Most don’t seem to spend too long in the Ebola zone, though one colleague tells me he will be here for five days.

I heard that humanitarian organisations act as travel agencies for some journalists, arranging flights, transfers, accommodation, interviews, even sometimes demanding they adhere to a specific publication schedule.

Dr. Gaston finds the correct letter and attempts to print it again, but now the printer is out of toner. The IT guy is unreachable. The doctor opens the printer and shakes the cartridge, releasing a cloud of pink powder all over his sleeves. He cooly brushes it away, gives me the letter, and runs to deal with yet another crisis.

As he hands me the letter, I think of the humbling scale of this endeavour in a setting where no bit of infrastructure – from printers to roads – can be taken for granted.

In the afternoon, I attend the daily debriefing by the Ebola response teams. In a large room, a couple dozen people summarise what happened that day. Dr. Gaston recounts a visit to a family opposed to vaccination, and how he convinced them to change their minds by bringing in local chiefs as mediators. “We broke the resistance,” he says.

How fast can you bury a baby?

Just a couple of weeks before I arrived in DRC, a car carrying Ebola responders was set aflame. The passengers miraculously escaped being lynched by a group of young people. (By December, the WHO said it had documented "approximately 390 attacks on health facilities" in 2019.)

With my fixer, Yassin Kombi, a local journalist, we head to the neighbourhood where the attack took place to talk with motorbike taxi drivers.

They taunt me: Ebola isn’t real, Ebola is a business. It’s a bit tense, but once we sit down and talk, they open up and explain what happened.

We climb on their motorbikes and they take us to a nearby high school to talk with students dispersed by shots fired by the police and the army during the burial of one of their classmates. The students had requested that the coffin be opened so they could see their friend’s body.

The next day, I go to the burial of an Ebola victim. This time, I witness the Ebola response from the perspective of the health workers, as I ride in a car with the Ministry of Health burial team.

They have a dangerous job. One tells me how he had to move house after his neighbours learnt that he worked for the Ebola response. Every night, stones were thrown at his house; his kids were scared. Now, they must walk seven kilometres to get to school.

He explains: “Our brothers from the community think that we are eating bread dipped into the blood of our brothers, that we plot, that we conspire so that our brothers die. So that’s the risk and dangers we face.”

He used to be a teacher. When I ask why he doesn’t return to such a safe job, he says: “No, no, no! It’d be a worthless work. The disease is still there, how can we stop?”

For this, he earns $300 that month, whereas he expected $450 – a “bonus” paid by the WHO on top of a separate Ministry of Health salary that has yet to materialise.

I know some expatriates doing much less risky jobs for the Ebola response and who earn similar amounts in a single day of per diems.

In front of our car, the coffin is in a pickup truck with a cross tied to its side. Behind us, in a small grey car, the family follows. They are burying their one-year-old baby.

As we near the cemetery, the burial team gets more nervous. When they get out, they do their job as fast as possible. The “safe and dignified burial” becomes a race.

The baby’s father is crying. I ask him if I can take photos. He doesn’t care. He looks at me. He looks through me. An old woman is lying on the ground, crying. Two teenage girls wail loudly, calling out to God.

Earth is thrown on top of the small coffin. The baby’s parents plant some bushes on top of the dirt mound. A cross is pounded in the ground.

“Someone yells out to the Ebola team: ‘mbwa’ [‘dogs’].”

Just 15 minutes after it began, the burial ends.

Still shaken by the speed, I hand my business card to the father in case he wants to get in touch, maybe to see some of my photos.

“What will I do with this?” he asks, as he pushes my hand away.

We are back in the car and driving away when someone yells out to the Ebola team: “mbwa” [“dogs”].

Rollerblading and other signs of ‘normal’ life

Over the next few days, I try to find out how people who may be sick with Ebola are treated, from their arrival at the hospital, to the diagnosis, and (hopefully) the recovery.

I go to the annex set up by MSF in the local health centre but managed by the Ministry of Health. I’m looking for patients who are quarantined because they are thought to have Ebola. Instead, I meet a psychology teacher, Malumalu, who spent five days there in isolation and turned out not to be sick.

A patient arrives on the back of a motorbike. There’s no more space in the annex, so she’s left on the ground outside the health centre.

A car carrying health workers turns up, and they get out to test her, but they’re missing bits of their protection suits. They wait for another team. A second car backs up as close as possible to the woman, the exhaust spewing fumes a couple of metres from her face. But the back door to this car refuses to open.

Two health workers wearing protective clothing from head to toe lift her from the ground and carry her to a third car that takes her to a transit centre to get tested for Ebola. I take some photos.

Later, I learn that she was discharged after three days. She didn’t have Ebola.

“No matter how many response workers are killed or how many Ebola deaths are recorded during the day, Beni’s main bar, Ishango, is packed every night.”

When, over the next weeks, I talk with half a dozen expats working for the Ebola response, they explain that the response efforts are often chaotic and bring great institutional violence upon the local people they aim to help – via actions as necessary as quarantining suspected cases or imposing burial rites.

Yet, no one wanted their name cited.

But no matter how many response workers are killed or how many Ebola deaths are recorded during the day, Beni’s main bar, Ishango, is packed every night with local residents drinking and dancing.

I’m there, too, trying to make sense of what I have seen that day, and trying to think about something else. I don’t see any workers involved in the response: for the most part, staff from humanitarian organisations tell me they aren’t allowed, or they’re discouraged from going out after dark.

On Sunday morning, I follow a group of rollerbladers who wake up early to train for competition. I’d love to write about them.

Wishful thinking: there’s no link to Ebola, so I doubt any media outlet will be interested. I take their photos and upload them on the group’s Facebook page.

The next day, I visit a traditional healer outside town. He boasts about the number of people he has cured of Ebola, right there in his “hospital” – composed of several mud huts. Workers for the Ebola response came to take some of his patients, he said, and they fled.

It dawns on me that some of his patients might have sat on the same couch as me. I imagine every surface infected by the deadly virus.

For 21 days, the period of incubation for the virus, I think about what I have touched, despite having received the experimental vaccine.

Ebola seems to be everywhere: deadly, mysterious, and invisible.

The “resistance” of local residents to the response teams seems to be everywhere, but it is visible. And, once you talk with those residents, their anger is no longer mysterious.

With reporting support from Yassin Kombi.

ef/js/ag