More than 11 months after an Ebola outbreak was declared in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, the viral disease has claimed more than 1,500 lives, infected 2,244 people, and spread across the border into neighbouring Uganda, where two deaths and three suspected cases were reported mid-June. A new confirmed case just 43 miles from South Sudan's border was reported Monday.

The New Humanitarian has been covering the deadly epidemic – now the second largest on record and the first to occur in an active conflict zone – from its outset, as it decimates whole families and communities.

Though the response has seen some success – more than 147,000 people have now received an experimental vaccination, which has proven effective in 97.5 percent of cases – violent clashes and attacks on Ebola workers and treatment centres have slowed relief efforts, causing cases to spike. Fear and mistrust of responders has led some locals to spurn treatment altogether.

A new flare-up of ethnic conflict in Congo’s Ituri province – one of two areas affected by Ebola – has displaced an estimated 300,000 people since June, according to the United Nations, posing a new threat to containment efforts.

Despite a decline in the number of new cases reported in major hotspots over the past few weeks, the World Health Organisation has said there remains a “high risk of geographical spread both within the DRC and to neighbouring countries”.

In mid-June, the WHO called the outbreak an “extraordinary event” but said it does not yet constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, or PHEIC. The declaration would have galvanised additional funding and international attention but resulting border closures could have negatively impacted Congo’s economy.

In a worst-case scenario WHO officials have said it may now take two more years to contain the virus, which killed more than 11,300 people between 2014 and 2016, mainly in the West African countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea.

“We may end up being around dealing with this outbreak for a long time," said Michael Ryan, executive director of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme.

Drawn from months of reporting by TNH, this briefing summarises how the pandemic got to its current stage, the risk of further contagion and its effect on communities in one of the world's most complex, longest-running humanitarian crises.

The crisis in numbers

- 2,244 Total number of confirmed cases

- 1,477 Total confirmed fatalities

- 174 Number of attacks on health workers between January and May this year

- 78 days Time it took for the virus to double from 1,000 to 2,000 cases

- 159 Number of armed groups operating in the Kivus as listed by the Kivu Security Tracker

- 1 million Estimated number of displaced people in North Kivu.

- 17 million Total population of Ituri and North Kivu provinces.

- 12.8 million Number of people in need of humanitarian assistance across DRC.

Where are the current cases?

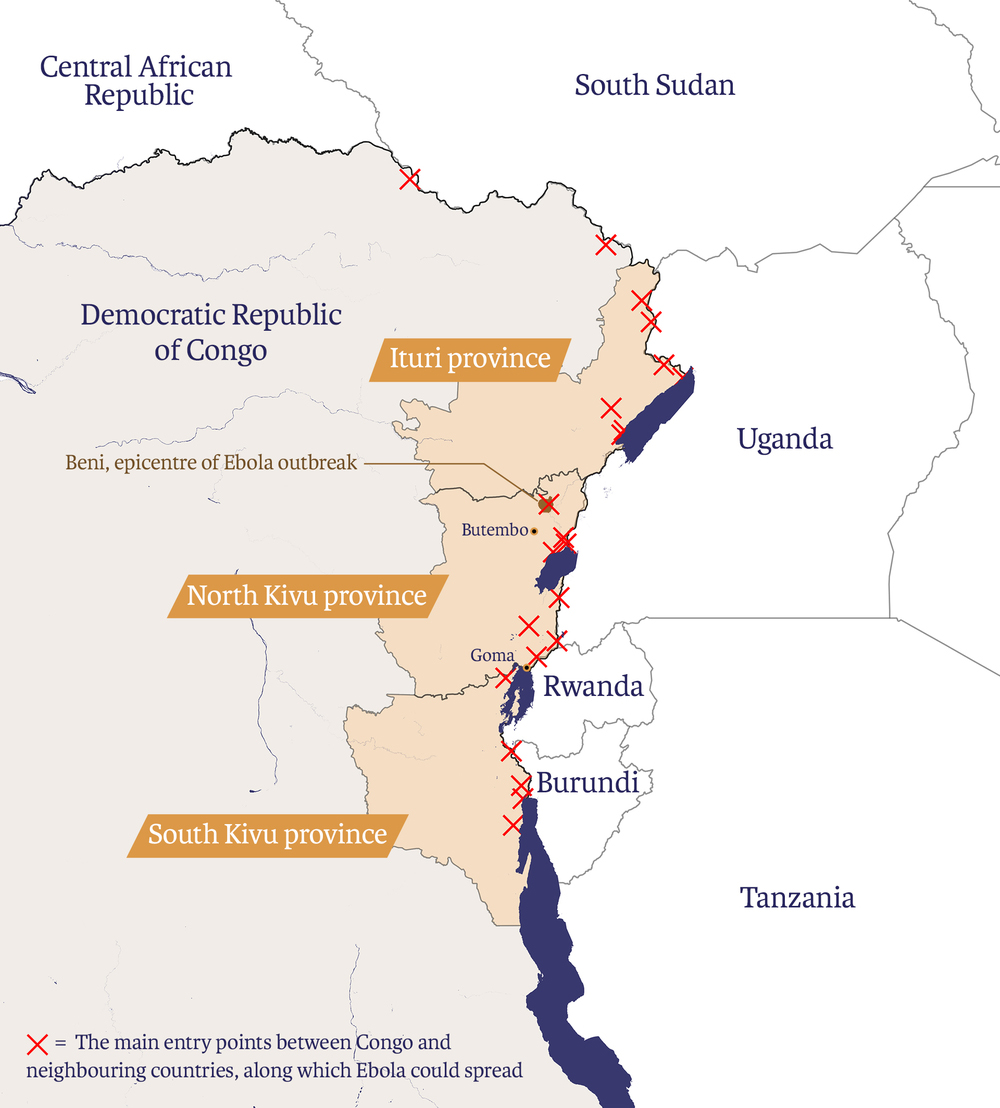

The outbreak is currently affecting towns and villages in North Kivu and Ituri, two conflict-torn provinces in eastern Congo that share porous borders with Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan. The two provinces are among the country’s most populous, with a combined population of around 17 million people.

In mid-June, a five-year-old boy and his 50-year-old grandmother died of Ebola in western Uganda in the first cases reported across Congo’s border. The victims had travelled to Congo with other members of their family to care for an elderly relative who was suffering from the virus. On Monday, an Ebola case was confirmed in Ariwara, a Congolese town roughly 43 miles from the border with South Sudan’s Yei River State.

Health officials say the Congo outbreak – which was officially announced last August – could have been stopped earlier if cases stretching back to April had been detected before transmission.

Early detection and response was hampered, however, by a lack of diagnostic equipment in North Kivu – which had never previously experienced an outbreak – and poor or non-existent roads, among other factors.

The new outbreak is the 10th Congo has faced since the virus was first discovered near the Ebola River in 1976. It began just a week after the Congolese government declared an end to a previous epidemic in the northwestern Equateur province.

What challenges are relief workers facing?

Insecurity and attacks on health workers have forced responders to suspend their work, giving the virus time to spread. While it took 224 days for the first 1,000 confirmed and probable cases to be reached, just 71 days later that number had doubled to 2,000.

Between January and May, a total of 174 attacks against Ebola workers and operations were recorded, causing five deaths and 51 injuries, including a Cameroonian WHO doctor.

Attacks have since slowed but not ended. Late last month an Infection Prevention and Control team was attacked by motorcyclists; a point of entrance checkpoint was burnt by arsonists; and a safe burial team came under attack by youths – all three incidents in Ituri.

While little is known about the identity of the assailants, the attacks are taking place against a backdrop of distrust between local communities and national authorities, as well as aid groups and UN peacekeepers.

The Kivus and Ituri have been at the centre of Congo’s conflicts for decades, and violence by dozens of armed groups continues almost on a daily basis. North Kivu alone currently hosts more than one million displaced people.

Since 2013, Beni – an Ebola hotspot – has experienced a particularly gruesome series of massacres that have cost hundreds of lives but garnered little international attention. Other treatable diseases like malaria, diarrhoea, and cholera continue to kill tens of thousands every year with similarly little fanfare.

By contrast, the Ebola outbreak has seen an influx of foreign aid and health workers, the scale of which seems disproportionate to many locals who have come to believe Ebola is simply a money-making scheme.

The outbreak was also politicised by last year’s discredited and long overdue presidential elections. The vote was suspended at the last minute in the North Kivu towns of Beni and Butembo, ostensibly to prevent the spread of Ebola. The decision fuelled suspicion that the virus was simply a pretext to disenfranchise the largely opposition-supporting population.

A study published in The Lancet found that around one in four respondents interviewed last year believe Ebola is not real. Disinformation has also spread via social media.

“Low institutional trust and belief in misinformation were associated with a decreased likelihood of adopting preventive behaviours, including acceptance of Ebola vaccines and seeking formal health care,” said the authors of the Lancet study.

Will the virus spread further?

With ongoing transmission, delays in detecting cases, and a third of victims dying outside of Ebola clinics, the WHO has said there is “a high risk” of further spread within Congo and to neighbouring countries – Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan.

Authorities in all three countries have worked hard to stop the outbreak spreading, but populations in border areas are highly mobile, with residents frequently crossing sides to visit relatives or conduct business. Border posts are often informal and hard to secure – a problem highlighted by the recent spread of Ebola to western Uganda.

A recent upsurge of violence in Ituri and Beni – close to the Uganda border – has added to the risk of spillover, with some displaced people fleeing into Uganda through unofficial crossings, where aid groups say they are not being tested for Ebola symptoms.

Uganda has vaccinated thousands of frontline workers in at-risk areas and has built several Ebola Treatment Units in districts bordering North Kivu and Ituri. But as the first cases are reported, Ugandan medics say they lack basic supplies.

Within Congo there are growing fears the virus could spread to Goma, the capital of North Kivu province. The city of one million people is about 300 kilometres from the outbreak’s epicentre, and sits on the border with Rwanda’s Rubavu district.

Only a fraction of health centres in Goma are currently prepared for a large-scale outbreak, while in Rwanda the disease could spread thanks to the country’s well-maintained road network and high population density.

Despite a peace deal in South Sudan, sporadic clashes have continued, especially in central Equatoria – a state that shares a porous border with Congo. Poor infrastructure, insecurity, and an acute lack of trained healthcare workers have made it hard to set up and monitor screening locations. The country’s health ministry has appealed for $12 million to boost its preparedness. The recent case in Ariwara – near South Sudan's border – will likely put the country on high alert.

Is the vaccination saving lives?

An unlicensed, experimental vaccine produced by the American pharmaceutical company, Merck, is being deployed on compassionate grounds and has proved highly effective, delivering roughly 97 percent protection for the 147,000 people currently inoculated.

The vaccine received a successful Phase III trial towards the latter stages of the 2014-2016 West Africa epidemic and was also used in the early stages of Congo’s Equateur outbreak last year.

So far it has been administered using a so-called “ring vaccination” method, which involves tracing and vaccinating the contacts of confirmed cases – followed by contacts of contacts.

But insecurity and distrust of responders has hampered the ability of health workers to reach and vaccinate contacts effectively, and a large proportion of new cases have arisen among unknown contacts, according to the WHO.

In May, the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts recommended expanding the population eligible for the vaccination and switching to smaller doses to cope with the extra demand. The experts also recommended introducing a second experimental vaccine produced by the company Johnson & Johnson, but the Congolese government is yet to approve this.

The Merck vaccine was originally engineered by scientists from the Public Health Agency of Canada in the early 2000s. Public money has supported much of the subsequent clinical development costs.

How could the response be improved?

As cases rise, the UN and leading aid groups have triggered a “system-wide scale-up” – the highest level of emergency response – putting the Ebola crisis on par with Yemen, Syria, and the cyclone response in Mozambique. The declaration is designed to increase international attention, release extra funding, and improve humanitarian coordination.

On 14 June, the WHO's emergency committee ruled for the third time that the crisis does not constitute a global emergency. But speaking after the decision, the WHO director general, Tedros Ghebreyesus, called for the international community to “step up its financial commitment” and plug a $54 million funding shortfall.

Aid groups and researchers are meanwhile calling for greater involvement of local communities to improve trust with international responders. This includes doubling down on communication and outreach, and providing locals with a better understanding of the virus and how it is treated.

The medical charity has criticised a heavy-handed, “militarised” response for alienating the public, with the Congolese police and military often forcing local communities to accept Ebola treatment. This has caused some locals to stay away from Ebola clinics.

But this drive to put local people at the forefront of the response puts them at greater risk, and recent TNH reporting reveals that even though they bear the extra burden they often get less say, recompense, and protection than foreign staff.

(TOP PHOTO: A mother holds her child in an Ebola quarantine, at the Ebola treatment centre in Beni.)

pk/ag