Policies put in place by the administration of US President Donald Trump have cut off access to asylum in the United States during the coronavirus pandemic, sent COVID-19-positive people back to Latin American countries — where outbreaks are now spiralling — and exacerbated an already dire situation for asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border.

Human rights groups worry that the damage done will outlast the pandemic. The Trump administration “found that the pandemic gives them the perfect excuse to do what they wanted to do since day one, which is end access to asylum at the southern border,” Charanya Krishnaswami, advocacy director for the Americas at Amnesty International USA, told The New Humanitarian.

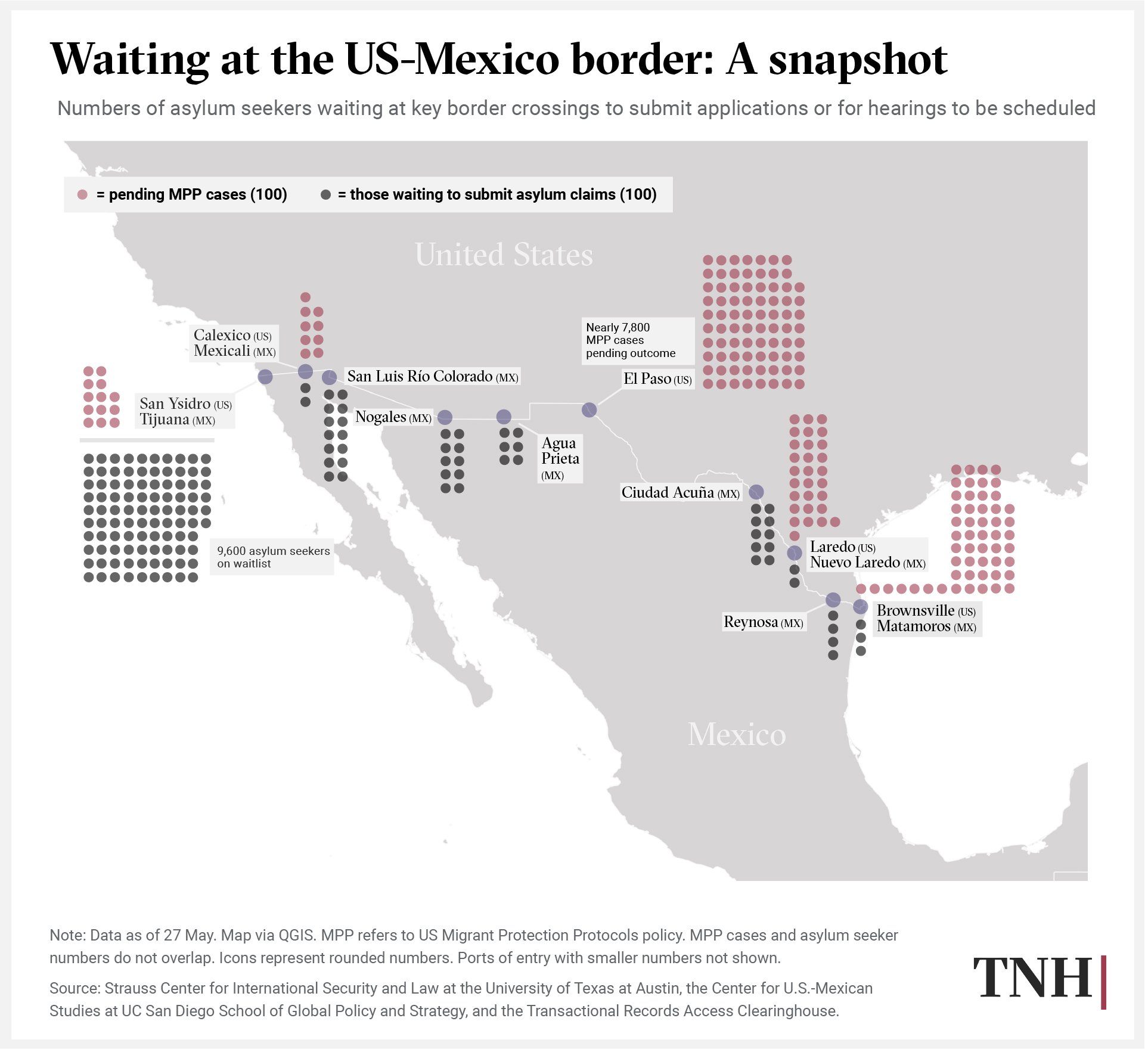

Due to policies put in place during the pandemic by the Trump administration, more than 40,000 people have been expelled from the United States after crossing the US-Mexico border and over 30,000 more asylum seekers are living in limbo in often dangerous situations in northern Mexico.

Implemented in the name of public health, the policies include the suspension of asylum hearings and an order issued in March by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US health protection agency, that paved the way for anyone who irregularly enters the country to be expelled immediately without being able to apply for asylum.

Travel restrictions and social distancing measures have had the unintentional side-effect of limiting access to asylum around the world during the pandemic. But human rights groups and public health experts say the Trump administration is using the virus as a pretext to effectively end access to asylum at the US-Mexico border even as other forms of travel have been allowed to continue.

“It’s extremely contradictory,” Paul Spiegel, director of the Center for Humanitarian Health at Johns Hopkins University, told TNH, speaking about the CDC order. “It never really made public health sense to say we’re going to stop the irregular migration... but we’re going to allow all this other movement.”

Instead of preventing new outbreaks in the United States – which has the highest number of confirmed coronavirus cases in the world – expulsions under the CDC order, along with continued deportations of people from immigration detention, “may actually be spreading [the virus] in other countries”, Spiegel added.

Meanwhile, the pandemic is intensifying an already difficult humanitarian situation for tens of thousands of people who have been made to wait in northern Mexico for the duration of their asylum processes by earlier Trump administration policies. It has also made it more difficult for cross-border aid groups to provide much needed support.

Here’s a look at some key questions on the Trump administration’s asylum policies at the US-Mexico border and their humanitarian consequences during the coronavirus pandemic:

What was the US policy before the pandemic?

“Asylum was already essentially cut off at the southwest border pre-pandemic,” Jessica Bolter, an associate policy analyst at the Washington D.C.-based Migration Policy Institute, told TNH.

The Trump administration views asylum as a loophole in the country’s immigration system and has put in place a range of policies aimed at severely curtailing people’s ability to lodge asylum claims at the US-Mexico border.

In 2018, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the US border control organisation, began implementing a policy known as metering that imposed limits on the number of people who can apply for asylum on a given day at ports of entry to the US. Thousands of people piled up in cities and towns on the Mexican side of the border, sometimes waiting six to nine months before they could submit an asylum claim.

“Asylum was already essentially cut off at the southwest border pre-pandemic.”

The metering policy was followed by the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) in 2019, also known as “Remain in Mexico”. An agreement with the Mexican government, the policy allows the United States to send asylum seekers from Spanish-speaking countries – and later also Brazil – back to Mexico during the duration of their asylum processes.

The Trump administration has also narrowed the criteria for asylum eligibility in the United States (including the recent proposal of a set of ultra-restrictive regulations), blocked people from applying for protection who did not already have an asylum application rejected in one of the countries they transited through before reaching the United States, and made an agreement to send asylum seekers from El Salvador and Honduras to Guatemala instead of allowing them to lodge claims for protection in the United States.

How has the pandemic affected the situation in northern Mexico?

For people who have been waiting for many months on the border, “the situation is pretty dire,” Kennji Kizuka, senior researcher at the US-based nonprofit Human Rights First, told TNH.

When the US suspended asylum processing at the end of March, there were around 14,500 people on informal metering lists in northern Mexico waiting to submit asylum claims at ports of entry and nearly 18,000 people who had been sent back to Mexico under MPP waiting for their cases to be processed in US courts.

The majority of those seeking asylum in the United States are from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador – an area of Central America known as the Northern Triangle where spiralling gang violence, homicide, extortion, and extrajudicial killings are fuelling a displacement crisis – or from Mexico, where similar factors have pushed tens of thousands of people to seek protection in the United States in recent years.

Even before coronavirus arrived, the Trump administration’s metering policy and MPP had created a humanitarian crisis for asylum seekers waiting in northern Mexico. The existing support system on the Mexican side of the border – set up to help people on the move – was quickly overwhelmed when the policies came into effect.

Shelters soon filled up, and asylum seekers crowded into rented rooms, stayed in cheap hotels, set up makeshift camps, or ended up homeless on the streets. People struggled to find work to provide for themselves while they waited, children couldn’t register for school, and access to healthcare was hard to come by, according to Kizuka.

Human Rights First has also documented over 1,000 violent attacks against asylum seekers returned to Mexico under MPP since January 2019. “There’s a great deal of insecurity and violence in that region of the border, and in particular targeting of asylum seekers and migrants,” Kizuka said. “Reports of kidnappings, people being raped and beaten and extorted, are very common.”

The pandemic has only made the situation worse. People have been stuck inside for months as shelters have locked down to try to prevent outbreaks. Others are living in crowded housing where social distancing is not an option as the coronavirus crisis in Mexico has become one of the fastest-accelerating in the world.

Violence has increased as drug cartels extort and kidnap more people to supplement reduced revenue from a slow down in drug smuggling activities. And there is no telling when the pandemic will end or when asylum processes will restart. There’s also no telling how many people have stayed in dangerous situations in their home countries or in transit countries because the possibility of claiming asylum in the United States is no longer an option.

At the same time cross-border aid groups that provide food, clothing, legal support, and medical care have found it more difficult to carry out their activities. Volunteer numbers and donations have plummeted. The supply chains for medical NGOs have been disrupted. And volunteers from the United States are wary of crossing the border to deliver aid or carry out activities for fear of accidentally transmitting the virus to asylum seekers.

“It’s affected everything,” Andrea Rudnik, a volunteer with Team Brownsville, a grassroots organisation based in Brownsville, Texas that provides meals and runs an educational programme in a makeshift camp for asylum seekers across the border in Matamoros, Mexico, told TNH. “Realistically, we’re not going to be able to provide services the way we did before, at least not for the rest of this year.”

What impact have expulsions and deportations had?

Concrete information about the more than 40,000 people who have been expelled from the United States under the CDC order since the end of March is hard to come by. “It is a black hole, and it’s very scary,” said Krishnaswami, from Amnesty International USA.

Data released by the US government does not contain detailed information about who is being expelled, where people are being sent, or what happens to them afterwards, and, because of the virus, human rights groups have not been able to carry out field research to monitor what is taking place.

Under the expulsion policy, people apprehended after irregularly entering the United States are driven to the nearest official border crossing and sent back to Mexico, or are returned to their country of origin without being processed.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that people who are apprehended are often expelled through remote ports of entry that are closer to the dangerous desert migration trails used by migrants and asylum seekers to enter the United States irregularly. “They’re… sent back to just really dusty, isolated towns where I think they’re effectively stuck,” Katie Sharar, communications director for the Kino Border Initiative, a cross border aid and advocacy group based in southern Arizona, told TNH.

On the Mexican side of the border – and in the countries people are flown back to – it is difficult to distinguish between people deported from immigration detention and those expelled under the CDC order.

In addition to the expulsions, the United States has continued to deport people from the interior of the country throughout the pandemic. Since the CDC order was issued, the US government has likely carried out more than 170 deportation flights to more than a dozen countries, according to a data set maintained by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington D.C.-based think tank.

At least 186 people deported or expelled from the United States have tested positive for the coronavirus after arriving in Guatemala, and COVID-positive people have also been sent back to El Salvador, Haiti, and Mexico, where at least one outbreak in a migrant shelter in the north of the country has been traced to a deportee from the United States.

Latin America emerged as a new epicentre of the pandemic in the past month, but it will be hard to tell to what extent – if any – US deportation and expulsion policies have contributed to the accelerating outbreaks. “Were [deportees] sufficiently quarantined that they didn’t spread [the virus] or were they the cause of, ultimately, community spread? I don’t think we’ll know that, or at least we won’t know that easily,” said Spiegel from Johns Hopkins.

What next?

It appears that – at least for now – the Trump administration’s policies, along with virus-related travel restrictions and border closures throughout Latin America, have reduced the number of people heading to the US southern border to apply for asylum or to attempt to irregularly enter the country, according to Bolter from the Migration Policy Institute.

Asylum hearings for people returned to Mexico under MPP are set to begin again on 20 July, provided that public health conditions allow for them to take place. But there isn’t much hope for people in the programme. Of the more than 40,000 people whose MPP cases have been completed so far, only about 2,000 have been granted some form of protection in the US.

The CDC order – after initially requiring renewal every 30 days – has also now been extended indefinitely, meaning that for the foreseeable future people will still be barred from requesting asylum at US ports of entry or after being apprehended irregularly entering the country.

If he is elected in November, Joe Biden, former vice president and the presumptive Democratic nominee running to oppose Trump in the presidential election, has pledged to roll back the Trump administration’s policies restricting access to asylum.

But as long as Trump remains in office, “even if the coronavirus abates, we don’t really expect the administration to lift these restrictions,” said Kizuka from Human Rights First. “They are just truly uninterested in offering protection to those groups of people who are looking for it.”

er/ag-js