Two horrific murders in Mexico City have fomented public outrage over the region’s long-standing femicide epidemic, just as aid groups are contending with a surge of women fleeing violence in Central America.

Ingrid Escamilla Vargas, 25, was found earlier this month skinned, dismembered, and disembowelled. Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett Antón, seven, was last seen alive leaving school on 11 February. Her corpse was found wrapped in a garbage bag, showing evidence of torture.

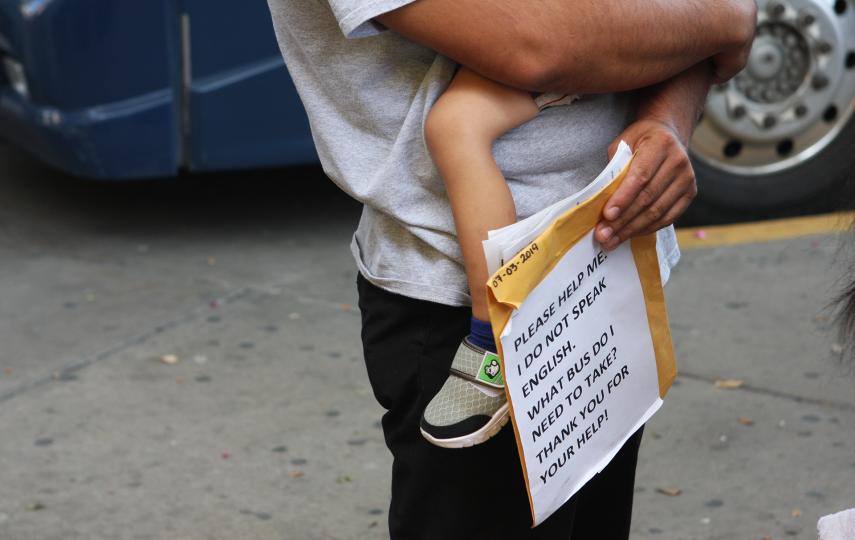

The cases, which sparked widespread street protests in Mexico, have also highlighted how authorities and humanitarian groups are struggling to handle an unprecedented number of women and children amassed at the southern US border or trying to get there to ask for asylum.

“Violence in Mexico and Central America, and violence against women especially, has contributed to a new wave of migration unlike any we have seen before,” said David Shirk, a political science professor and expert in US-Mexico border policy at the University of San Diego, where he directs the Justice for Mexico project.

Benita, who asked that only her first name be used to protect her safety, runs a rural organisation south of Mexico City that seeks to curb migration. She blames much of the vulnerability Latin American women face on a deeply rooted “machismo” culture, saying too many men use it as an excuse to treat women and girls as possessions they can physically and sexually abuse with impunity.

Such vulnerability is even greater for migrant women, many of whom flee dangerous situations in the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador only to face sexual violence, extortion, and human trafficking on their journeys north.

New pressures

US President Donald Trump’s policies have put additional pressure on all migrants travelling through Mexico in the past year. So-called “metering” limits the number of asylum seekers processed daily at US border crossings; Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) – also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy – have forced tens of thousands of asylum seekers to wait out their long application procedures south of the US border, often in violent urban centres; and Washington has successfully pressured the Mexican government to crack down on migrants heading north.

Read more → The fallout of US migration policies in Mexico and Central America

In addition, the Trump administration has forged “Safe Third Country” agreements with Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras that effectively disqualify migrants from seeking asylum in the United States if they travel through these countries first. Deportations, mostly of women and children, have already begun to Guatemala and are expected to be stepped up to all three Northern Triangle countries.

However, femicide in those same nations is a massive problem that Northern Triangle governments have failed to get to grips with for years – although statistics are incomplete because many countries lump male and female murders together, and because sexual assault and domestic abuse often go unreported.

Among the statistics that are available: in 2018, the UN reported that El Salvador had 13.49 femicides for every 100,000 women, the highest rate anywhere in the world; and a 2014 report by the World Health Organisation found that Honduras also had a rate of more than 10 female homicides per 100,000 women.

Latin America and the Caribbean account for 14 of the 25 deadliest nations in the world for women. There is rarely justice. As many as 98 percent of gender-related killings go unprosecuted in Latin America, according to the United Nations.

There are a number of other factors – including US and Mexican immigration policies, chronic poverty, and drought made worse by climate change – but, more and more, women and girls are simply fleeing the region. US Border Patrol data shows the number of women caught crossing the Mexican border more than tripled from 2018 to 2019 to nearly 300,000. The proportion of women versus men leapt to 54 percent from 32 percent.

“The migration of the 1980s, and most previous generations, was predominantly migration of young men,” Shirk said. “However, for a variety of reasons, the current wave of immigration is arguably the largest wave of women and children that the United States has ever seen.”

Sticking together

At the migrant shelter Casa de los Amigos in Mexico City, intern Alexandra Pfeiffer said one way that young and female migrants have sought to protect themselves is by travelling together in large numbers – referred to often in the media as “caravans”.

“Migration is hard and dangerous,” she said. “Caravans are a safety mechanism for women and help ensure their survival. Often-times, they’re leaving their husbands, or their husbands have been murdered. There are sex traffickers and (the women) must band together for safety.”

For aid groups, the shift in who is migrating and why – it used to be more single Mexican men for economic reasons – requires a new emphasis on women and children and also on providing psychological services.

Travellers in one recent caravan showed increased signs of trauma when they sought aid from Cafemin, one of the larger migrant centres in Mexico City. It has been open for about three years and is run by Roman Catholic nuns.

“We’ve noted increased psychological and psychiatric problems, which are considerably serious,” said Maria Soledad Morales Ríos, a coordinator at Cafemin. “It wasn't until the recent caravan that we noticed this increase… Now they arrive with more physical injuries, and the women are more generally wounded and fragile upon arrival.”

While all migrants risk trauma during their journey north, women and girls are especially vulnerable to sexual assault and many women in transit to the United States need treatment for trauma after fleeing extreme violence.

A strained response

International organisations responding to the crisis include Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). The group has operated for years in Mexico and the Northern Triangle and noted in its 2018 annual international report that the number of women, children, and families attempting the trek north had increased along routes traditionally dominated by men.

In 2015, MSF began a partnership with a shelter known locally as “La 72” in Tenosique, Tabasco, one of the main points of departure for migrants’ journeying north through Mexico and on to the United States.

La 72 took in over 14,000 migrants in 2019, mostly from the Northern Triangle. The clients fled “institutionalised, structural, organised violence in their country of origin”, said the shelter’s director, Ramón Márquez.

“Between 2013 and [2018], the female presence at La 72 has increased by a factor of about three,” he said. “In the case of underage women, the increase has been dramatically obvious as well.”

Women entering Mexico need aid organisations that “will regularly and consistently treat their case in secret, [because] they could be victims of human trafficking networks”, Márquez said.

“Violence and inequality are gendered.”

La 72 has adjusted its procedures to emphasise mental health services for female clients who need to process the violence they’ve experienced, as well as general feelings of abandonment, loneliness, homesickness, and stress associated with immigrating.

MSF provides La 72 with a staff of five to conduct both physical and mental health checks. The workers include two psychologists, a physician, a nurse and a social worker, according to Márquez.

A broad swathe of humanitarian responders interviewed by TNH emphasised the need to provide more mental healthcare for women and girls en route to the southern US border.

“In this society, women are the most vulnerable,” said Esperanza Palma, a political science professor at Mexico City’s Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana. “Violence and inequality are gendered.”

jw/sl/ag