UN and Red Crescent officials are set to begin a voluntary evacuation plan this week for thousands of displaced Syrians in the no man’s land camp of Rukban, but many residents are fearful of returning to Syrian government-held territory and say there are no new options.

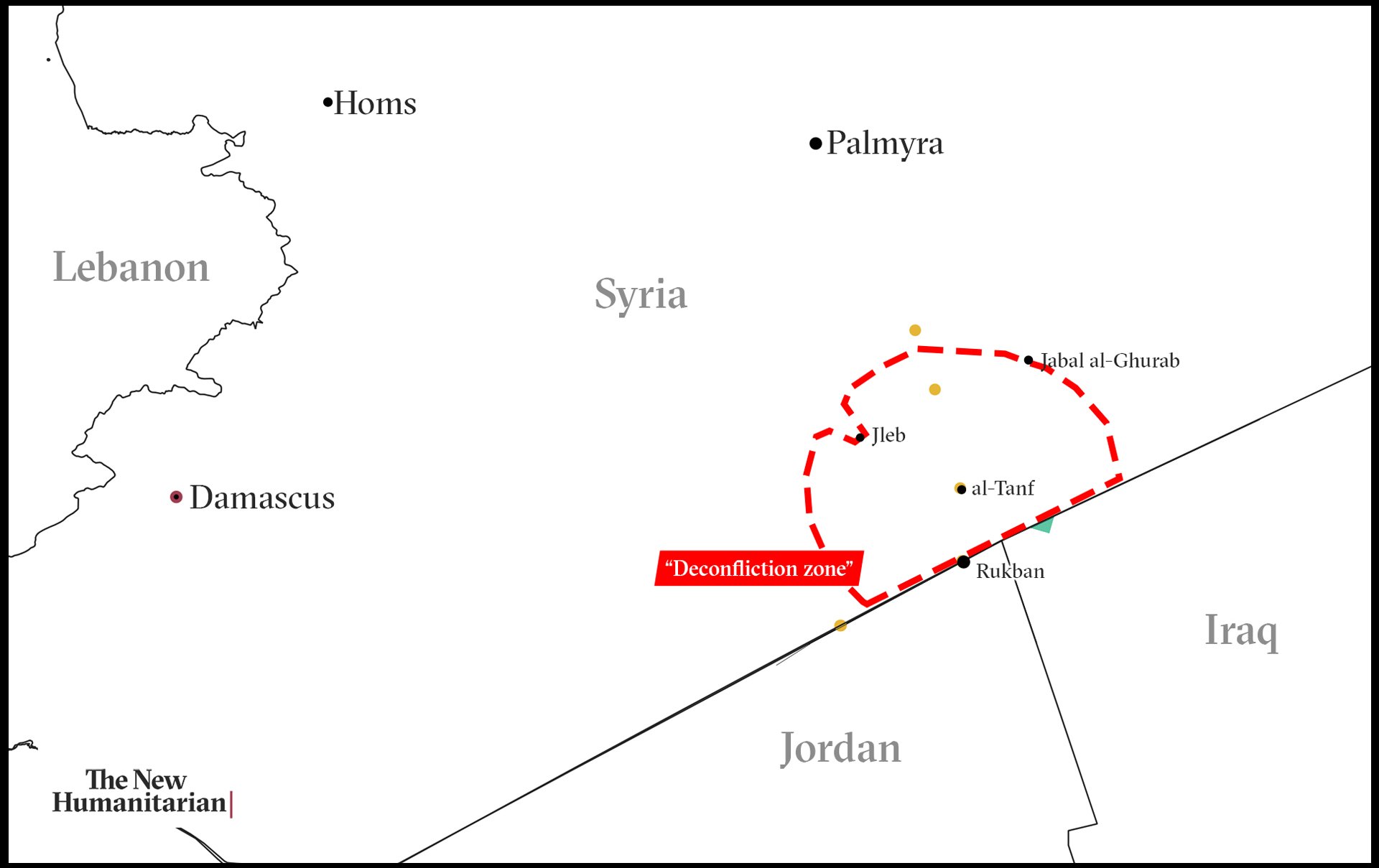

As many as 50,000 people fled to Rukban – near a US military base in a protected zone and close to the borders of Syria, Jordan, and Iraq – following the rise of so-called Islamic State and civil war in the eastern Homs desert region in 2015.

It’s estimated that between 11,000 and 24,000 Syrians still inhabit the desert camp, where residents have lived in increasingly desperate conditions since 2018 when aid access from Jordan was cut off apart from the occasional UN and Red Crescent convoy.

Activists and aid workers say the latest visit to Rukban seems little more than a message for the community to leave, and fear for the fate of thousands who may intend to stay, as well as those being pressured to return.

A maximum of 24,000 displaced Syrians remain in Rukban, according to the latest UN estimate from late July. A recent tally by Amman-based research group Etana has placed the number of remaining residents significantly lower – at 11,000.

Before the war, Rukban was an empty corner of eastern Syrian desert along the border with Jordan. Only a lone highway stretched through the landscape, part of an international artery linking Baghdad to Damascus.

Displaced Syrians began fleeing to the area after a series of Islamic State invasions on their hometowns in eastern Homs province. With a border crossing nearby, the roughly 50,000 people who settled there never meant to stay in Rukban for long.

But they were barred from entering Jordan after an IS-claimed car bomb in 2016 killed several Jordanian soldiers at a nearby border post. Ongoing battles in eastern Syria prevented their return home. The settlement soon became a sprawl of makeshift mud homes and breeze block markets, where traders sold goods brought in by smugglers crossing the desert from government territory.

There are no doctors, and the harsh desert conditions regularly kill. At least 12 children died within the first two months of 2019, according to UNICEF. Nearly half of them were newborns. The only formal medical care is available at a UN-run clinic just across the border in Jordanian territory – but only for out-patient visits. Some critical cases are taken to hospitals elsewhere in Jordan.

The camp sits within a 55-kilometre zone controlled by a US-backed rebel militia based at the nearby al-Tanf garrison.

Damascus repeatedly criticises US presence at the base, while rarely granting the UN or the Red Crescent access to Rukban via Syrian territory.

US troops stationed at al-Tanf appear to have done little to help camp residents living within the 55-kilometre zone of their control, though their Syrian affiliates, the Mughawir a-Thowra rebel group, announced it had delivered unspecified “aid” supplies to Rukban last week.

Jordan, spooked by the 2016 car bomb, has meanwhile refused to allow aid deliveries to the camp from its territory since 2018, when it permitted supplies to enter Rukban via crane. Officials in Amman have since called Rukban “Syria’s responsibility”, rather than their own.

A UN statement on 8 August said the mission would “assess needs and determine the exact numbers of those who want to leave, assist voluntary departures from Rukban, and provide relief to those remaining”.

But no aid supplies will be provided in the first round of visits, according to an announcement circulated to camp residents on the messaging service WhatsApp. It said the first visit would begin on Thursday and would last five days.

The message bears no signature, but residents said they received it from UN representatives. Two UN officials and a diplomatic source, insisting on anonymity due to the sensitivity of the operation, confirmed that the message reflected the mission’s plan.

A 13 August statement from camp leaders reacting to the plan called for “regular, organised food and medical aid to those who wish to remain in Rukban”, international protection, and the option of a safe passage for residents to opposition-held northern Syria.

Hedinn Halldorsson, a spokesperson for the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, confirmed to The New Humanitarian that the UN/SARC mission was “being prepared”, but declined to provide further information about timing.

Officials from OCHA, UNHCR, and UNICEF either declined to comment on the convoy, citing a policy not to speak to the press about the operation before it launches, or did not respond by time of publication. A SARC spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.

The planned visit follows months of severe food and medicine shortages in the informal border camp. Residents have blamed the worsening crisis on pro-Syrian-government forces blocking vital desert smuggling routes that once supplied the camp with everything from food to baby formula to medical supplies and soap.

Residents reached by TNH by phone and message services said supplies were low. “We wish we could receive aid supplies,” one camp resident, who handles informal charitable donations said, adding that his supply point was all but empty.

‘Give us another choice’

“I’m not considering going back to regime territory,” Rami, a young Rukban resident, told TNH, requesting a pseudonym for security reasons. Like others, he had heard from recent returnees about prolonged stays at reception centres in Homs city, and accounts of military conscription. Those he spoke to had returned to Homs aboard government bus convoys as part of a Russian-backed “humanitarian corridor” out of the camp.

Rami said he felt the upcoming UN/SARC convoy presents people like him, who don’t wish to return to government territory due to fear of reprisals, with few options, especially as remaining in Rukban means coping with a deteriorating humanitarian situation. There is a smuggling route – via motorcycle, and only for men – from the camp to northern Syria, but Rami said he couldn’t afford it and didn’t want to risk the dangerous desert journey.

“Give us another choice,” he said.

Rami, and several other camp residents who spoke with TNH, said they would prefer safe passage to opposition-held territory in northern Syria.

“We don’t want to return to regime territory,” said Yara, a mother of six living in Rukban, also speaking on condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

Yara and her husband are struggling to afford the costs of feeding their family after her sewing business and his repair shop in Rukban lost customers, but they’ve ruled out going along with the UN/SARC evacuation plan to Homs.

“Returning to the regime isn’t safe,” she said. “What we want is to go to the north to find a safe area where we can stay, an area with stability.”

Most of those who left the camp have reportedly returned to their home areas in Syrian government-held areas after a brief stay in transit centres in Homs.

A May study from the Euopean Institute for Peace think tank found that, in common with other returnees to Homs and other parts of the country, some of the evacuees from Rukban are being “detained, ill treated, and forced to undergo interrogation and reconciliation”.

Some Rukban residents with family members who have left say their loved ones have alleged abuse in the government-run “reception centres” in Homs. Occasional UN inspections of transit centres in the city reported no ill treatment, but the UN has no capacity for monitoring and interviewing returnees once they reach their final destinations.

The evacuation plan

According to the WhatsApp message received by camp residents, after interviews, SARC plans to issue an “ID card” to those who agree to leave – many of those displaced for years by the war have lost their official paperwork.

The message says relief items and free transportation to transit centres in Homs will be provided in a subsequent operation. Special arrangements can be made for those with acute health or other issues.

A senior aid official, who said they “vehemently disagreed” with the approach, pointed out that this operation is unlike three previous UN/SARC convoys that had delivered dozens of truckloads of food, medicine, and other supplies across the front line.

The upcoming mission is to “figure out who’s who in there”, and prepare to get anyone out who “even remotely” wants to leave, the official said, asking to remain anonymous to protect sensitive professional relationships.

The WhatsApp message says those who don’t plan to leave will meet UN officials separately from SARC “to try to find sustainable solutions”, and that those meetings, including “community representatives”, will “assess key needs and understand the requirements of those who have chosen to stay”. Those who stay will receive unspecified “relief items” later.

In a survey conducted in February, about 14 percent (5,700) of the estimated 41,000 Rukban residents at the time said they either did not want to leave or would only consider going to opposition-controlled parts of Syria. That group largely said they feared reprisals when they return to areas of Syrian government control.

Rukban is thought to house members and families of rebel armed groups as well as civilians, all drawn largely from tribes in the wider Homs province.

The February survey suggested that, in principle, 95 percent of Rukban residents wanted to leave. But universally they had worries about safety and security at their destination. Many were concerned about a lack of official papers and some feared forced conscription.

About 17,700 people have voluntarily left Rukban since February, after the residents were offered transport and assurances of safe passage from the Syrian and Russian authorities. Because some others in the camp have taken clandestine routes to leave, estimates of the remaining population from UN and other analysts vary from 11,000 to 24,000.

(Additional reporting by Ben Parker.)

(TOP PHOTO: A member of the Syrian Arab Red Crescent on a bus with displaced people from Rukban at the Jordanian border.)

me/bp/ag