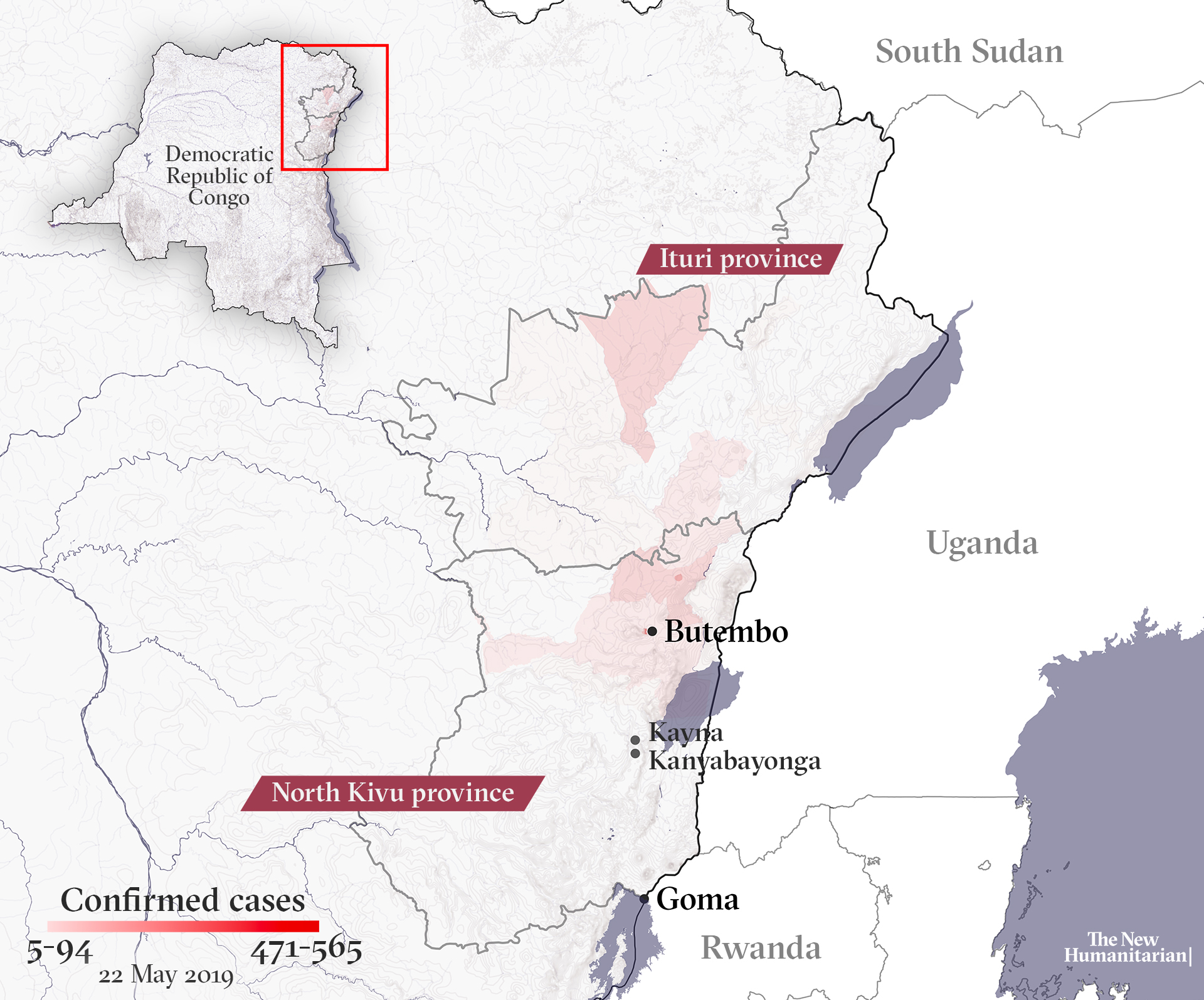

The second-largest Ebola outbreak ever continues to spread, and health officials now say it’s likely to reach the populous city of Goma. Once there, the risk of it spreading beyond the Democratic Republic of Congo to Rwanda, South Sudan, or Uganda increases.

Only a fraction of the health centres in Goma, the capital of North Kivu province, are prepared for a large-scale outbreak. The city, about 300 kilometres from the outbreak’s epicentre, sits at a major trade and migration crossroads and borders Rwanda, where Kigali’s international airport is only 160 kilometres away.

“I wouldn’t say (the spread to Goma) is inevitable, but it’s highly probable,” said Ray Arthur, director of the Global Disease Detection Operations Center at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the past three weeks, the number of areas with reported infections has increased from 21 to 22, with the newest affected area lying between Butembo – a city and trading hub near the epicentre – and Goma, said Arthur. Health zones where transmissions had previously stopped are now seeing new cases again.

If the disease reaches Goma, it will have far-reaching regional implications.

“There would be a whole set of political factors, a huge impact on the economy, and a huge social impact,” said Tariq Riebl, emergency response director for the International Rescue Committee, adding that there would be a domino effect regionally.

“The longer transmission goes on, the more likely it will get to one of those countries.”

While cases in densely populated and well-connected Rwanda would drive up the risk of wider regional spread, South Sudan and Uganda both suffer from an acute lack of trained healthcare workers. The security situation in South Sudan, where sporadic clashes continue, would pose a major challenge, while none of the three neighbouring countries have enough equipped clinics to deal with a large-scale outbreak.

“The longer transmission goes on, the more likely it will get to one of those countries,” Arthur said.

If the WHO declares the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, or PHEIC, that would likely lead to travel and trade restrictions – measures that could complicate humanitarian operations if border crossings are closed or suspended.

The WHO decided – for a second time – on 12 April not to declare the Ebola situation in Congo a PHEIC, but is under increasing pressure to do so from some public health experts. One concern if it does is that resulting border closures might increase the risk of transnational spread due to more people travelling illegally through porous borders.

With wider spread now looking likely, more staff from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Médecins Sans Frontières, UNICEF, and the World Health Organisation – as well as from other groups and NGOs – have been deployed to Goma.

There is currently no dedicated Ebola treatment centre in Goma, so isolating patients may be difficult. Hundreds of small clinics are scattered around the city across a large area, which would make it harder to monitor people if they became sick. There is also a shortage of trained nurses.

More than 1,860 cases of Ebola have now been reported in North Kivu and neighbouring Ituri province, and more than 1,240 deaths. Apart from the 2013-2016 West Africa epidemic that killed more than 11,300 people, this is the deadliest outbreak since the virus was first discovered near the Ebola River in Congo in 1976. It is also the first in an active conflict zone, as dozens of armed groups operate in North Kivu and Ituri, and violent clashes are common.

In recent weeks, mistrust has grown and attacks against health workers have risen, making the outbreak even harder to control. More than 120 violent incidents have occurred since the start of the year, with a Cameroonian doctor killed last month.

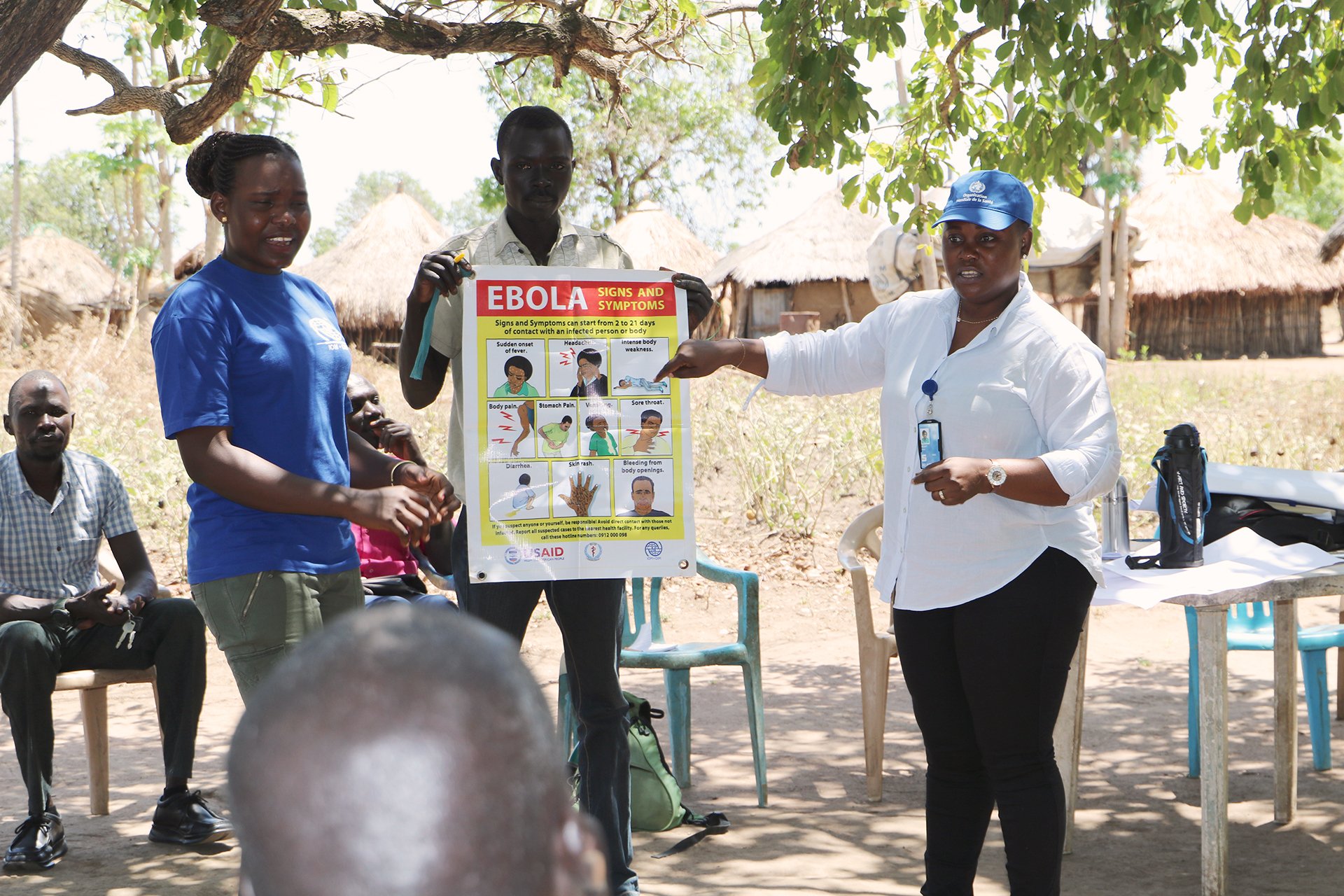

Misinformation is also hampering containment efforts. Some believe the virus isn’t real, or that a vaccine is dangerous. Others believe the government and foreign aid groups are profiting from the disease at their expense.

“All eyes are on Goma,” said Anne Rimoin, a professor at UCLA’s department of epidemiology and director at its Center for Global and Immigrant Health.

Deadly harbingers

Earlier this year, one case illustrated just how close Ebola was to Goma’s doorstep.

In January, a family travelling on the main road from Goma to Butembo was stopped at a checkpoint at Kanyabayonga, about 150 kilometres from Goma, according to Jessica Ilunga, a spokeswoman for Congo’s Ministry of Health – with several others familiar with the case. Six of the family members were found to have Ebola, and by the time the transmission cycle had run its course 21 members of the family had died.

“All eyes are on Goma.”

The first probable cases of Ebola appeared as early as April 2018, months before the epidemic was declared in August. According to Ilunga, a combination of factors hampered early detection and response, meaning early cases were only identified weeks after transmission had already begun.

“If the outbreak had been detected and declared earlier, it would have been easier to contain,” said Rimoin. “Outbreaks are like wildfires. It’s much easier to stomp them out when they are small and easily extinguished.”

When the epidemic began, models based on smaller outbreaks were used and didn’t accurately reflect the level of impact that armed conflict would have on response operations and in containing the disease, said Whitney Elmer, country director of Mercy Corps, an international NGO that has been providing sanitation, hygiene, and prevention kits to communities.

“It has made the structure in place perhaps not as efficient,” Elmer said, adding that one of the things that has hurt the overall response in Congo has been not engaging the community enough or integrating community acceptance into all levels of the response.

Another missing part has been how to negotiate humanitarian access with armed groups. It’s not too late to make “big and strategic changes” in the response, Elmer said. “This epidemic is not going to be stopped quickly.”

Up until the West Africa epidemic, Ebola had largely been confined to small or remote areas of Central Africa.

A smaller outbreak in Congo’s northwestern province of Equateur was brought under control just before the North Kivu outbreak was declared. Nurses in Equateur were credited for reporting the first cases quickly in May 2018 and alerting the authorities – rapid action that helped to contain that outbreak.

But health officials say spotting the disease can be tricky as it’s difficult to identify in its early stages. Many symptoms of Ebola – fever, headache, and weakness – are also common signs of illnesses such as malaria or typhoid. Bleeding is not always present in Ebola cases. And early cases in North Kivu were also spread out over several weeks, making it harder to realise there was a problem.

North Kivu had also never experienced a major Ebola outbreak before and, being remote, lacked the necessary diagnostic equipment, making it difficult in the early days to trace whether people had infected others or if deaths were attributable to the disease. Reporting cases quickly was also hampered by poor phone service and power outages. Because of poor or non-existent roads, samples could take several days to get to labs where they could be tested.

At the same time as the earliest cases were appearing, local healthcare workers were also on strike over stipends for working in high-risk areas, Ilunga said. Although many continued serving patients, there were lags in sending data to the national government. According to Ilunga, by the time the government was informed, there had been 30 cases and some had already reached Beni – another large town to the north of Butembo.

“We could have stopped it earlier,” she said.

Concerns at Rwanda’s border

As health officials and medical responders look ahead to containing any expanded outbreak, the well-travelled border with Rwanda is of particular concern.

An estimated 100,000 people cross the border each month into Rwanda, which has one of the highest population densities of any African country. Well-maintained roads in the country also offer greater ease of movement – and potential spread of disease.

Although there have been no known Ebola cases in Rwanda yet, at least one high-risk contact was reported to have been a Rwandan national. Details on the case are still being investigated but it was thought the person could have had contact with others in Rwanda. High-risk contacts are people who have likely been exposed to others who have been infected.

The Rwandan government has identified 15 districts that need to prepare for the possibility of treating the disease, including Kigali.

Closing the border in the event of a large-scale outbreak could have serious economic consequences, as it is a key trade route between the countries. In addition, humanitarian needs may be exacerbated or unmet for more than one million people displaced, largely by conflict, on both sides of the frontier.

Poor infrastructure and insecurity in South Sudan

South Sudan, meanwhile, has been ramping up its Ebola preparedness, but gaps in funding, coordination, and access still remain challenging, said Richard Lako with the country’s national Ebola task force.

Southern Sudan experienced three outbreaks – in 1976, 1979, and 2004 – but none were thought to have resulted from cross-border transmission. Some cases are thought to be linked to infected fruit-eating bats, though the specific origins of the pathogen have never been identified.

South Sudan signed a peace deal in September in an attempt to end a crippling five-year civil war that has killed some 400,000 people and displaced millions. Even though fighting has subsided, ongoing clashes between militant groups and government forces continue, especially in central Equatoria – a state that shares a porous border with Congo.

“There are forest areas between communities in South Sudan and the Congo, and these people can’t be screened from the other side,” Lako told The New Humanitarian. “It’s a big worry if those people sneak in… it’ll take us time to get in and control the issue.”

Poor infrastructure coupled with insecurity made it hard to set up and monitor screening locations. Some 24 screening sites – half the number needed – have yet to be established, officials said.

Compounding the lack of access is a shortage of funds. Less than 80 percent of the first phase of the response in South Sudan was funded, and at least $18 million is needed to fund the second half of this year, according to the Ministry of Health.

Although emergency helplines have been set up, minimal phone service in central Equatoria means that few may be able to access them.

For Uganda, ‘A matter of when’

Nearly one million people travel each month between Congo and Uganda, some of them ending up in the capital of Kampala or its nearby international airport.

“It’s now a matter of when” Ebola spreads to Uganda, according to Sarah Opendi, Uganda’s state minister for health.

Between 10,000 and 15,000 people cross the border each day. On market days it is more.

Uganda has implemented several preparedness measures, including automated temperature scanners at the international airport and border entry points, according to Innocent Komakech, a WHO emergency response official.

Thousands of health workers are also being vaccinated.

“We know anytime we might get a case,” Opendi told TNH.

pd/bp/vt/oa/sm/so/ag