Uganda has sent rapid response teams to the western town of Bwera to help contain the spread of Ebola from the Democratic Republic of Congo after three cross-border cases were confirmed, including a five-year-old boy who died on Tuesday night.

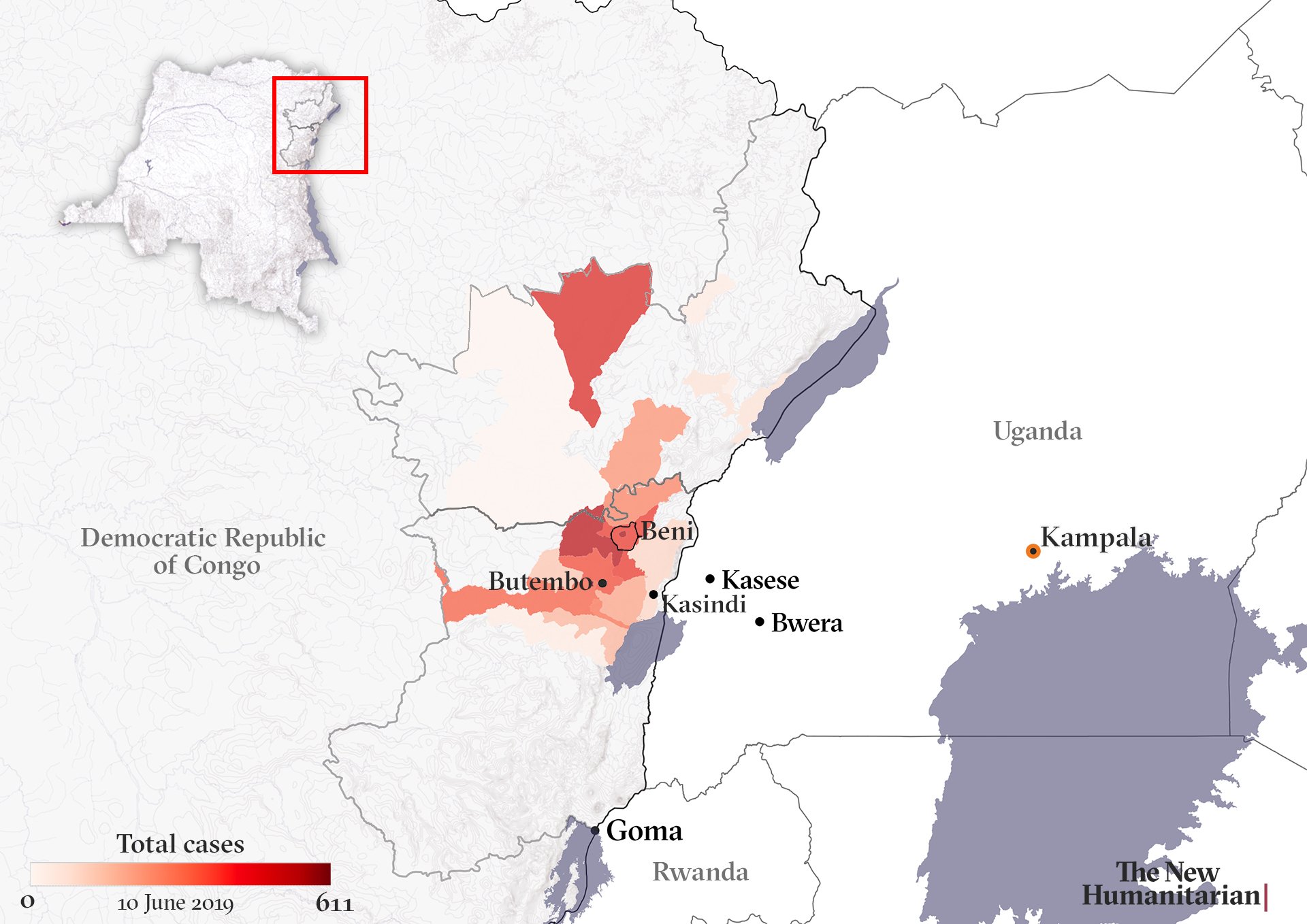

Congolese authorities – backed by the World Health Organisation and international NGOs – have been struggling for 10 months to contain an outbreak of the deadly virus that was declared in August in the restive eastern provinces of North Kivu and Ituri.

Attacks on treatment centres and healthcare workers – as well as a complex mix of broader community distrust and political factors – have made it hard to stamp out the outbreak, which is the first in an active conflict zone and now the second deadliest ever.

As cases have risen above 2,000 – with 1,396 deaths in Congo so far – concern has grown that the epidemic could spread to neighbouring countries: not just Uganda but also vulnerable war-riven South Sudan, and other places like Rwanda and Tanzania.

This briefing looks at how the virus spread to Uganda, what the response has been, and what it all means for wider efforts to halt the outbreak.

What happened?

The dead boy’s father is Ugandan and the mother Congolese. Both resided in Kasese, a town in western Uganda about 25 kilometres inside the border.

The mother and child were among several family members who had travelled to Mabalako – one of the epicentres of the outbreak in Congo – to care for the mother’s father, who subsequently died of Ebola at the end of May.

According to the Congolese health ministry, 14 members of the family – 12 of whom were already symptomatic – arrived recently in Kasindi, the Congolese town on the other side of the border from Bwera.

Officials at a border health checkpoint noticed their condition and would not let them pass, transferring them to a transitional isolation centre at Kasindi hospital.

Six members of the family, including the boy, subsequently left the isolation centre and headed for Uganda, crossing the border on 10 June on foot using an unofficial route to avoid health checks.

The Congolese health authorities notified their Ugandan counterparts, who found them at Kagando hospital, between Bwera and Kasese. The boy – who was vomiting blood – and the other five family members were taken to an Ebola treatment unit in Bwera.

Blood samples from the boy’s grandmother and three-year-old brother – who also exhibited “Ebola-like” symptoms – were sent to the Uganda Virus Institute for testing and came back positive on Wednesday, according to the WHO.

What has the response been?

At a meeting in Kasese on Wednesday between Ugandan and Congolese health teams, it was agreed the five surviving family members – all Congolese nationals – should be transferred to the treatment centre in Beni, the main city in Congo affected by the outbreak.

Uganda’s health ministry and the WHO have dispatched a Rapid Response Team to Kasese to trace contacts and monitor people at risk, WHO said in a statement.

The government has also called for the suspension of market days and mass gatherings in the border regions.

The vaccination of people who may have come into contact with the family and other non-vaccinated frontline health workers missed in an earlier round of inoculation is set to begin on Friday.

WHO spokesperson Tarik Jašarević said in an emailed response to The New Humanitarian that "500 vaccines were being driven overland from the DRC and an additional 3,000 would be sent from Geneva."

Uganda has been preparing for a possible outbreak for the past eight months.

It had already vaccinated nearly 4,700 health workers in 165 health facilities – including at Kagando hospital and the Bwera Ebola Treatment Unit.

Surveillance teams at health centres and within communities have been following up Ebola alerts – there have been more than 70 since May – and health workers have received training to recognise the symptoms of Ebola, Jašarević noted.

The Uganda Virus Institute had already tested 50 samples. The 51st, the boy’s, was the first positive result, Uganda’s health ministry said.

Does Uganda have previous experience of Ebola?

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus tweeted: “I commend [the Uganda Ministry of Health] for responding quickly to the identification of a case of #Ebola. #Uganda has experience managing #Ebola and has been preparing for months for this eventuality.”

Prior to this, Uganda has dealt with five Ebola outbreaks. The largest, in the northern town of Gulu in 2000-2001, killed 224 people – the third deadliest epidemic on record.

“Uganda is relatively well prepared” to deal with the current outbreak, said Delphine Pinault, country director of CARE International, an NGO involved with the response.

But in recent weeks there have been signs of “preparedness fatigue”, she told TNH. “This first confirmed case is a reminder that preparedness must be maintained at the highest level at all times given the deteriorating situation in DRC.”

In May the UN declared the need for a major scale-up of the Ebola response in the DRC, to include a broader vaccination strategy and closer community consultation.

Urging the UN to follow through with that plan to help avoid a regional epidemic, Mercy Corps country director in Congo Whitney Elmer said: “Given Uganda’s levels of Ebola preparedness, we are hopeful the number of cases in that country will be limited; however, we are deeply concerned for countries such as South Sudan that do not have the infrastructure to handle an outbreak.”

How porous is the border?

Uganda shares a 2,698-kilometre border with the DRC. Kasese has been categorised as a high-risk district, with travellers screened and vehicles decontaminated. There is a sizeable business community in Kasese and extensive cross-border networks link farmers, intermediaries, and small traders in the region, according to a briefing by the social sciences forum, Anthrologica.

Between 20,000 and 25,000 people cross daily at the Kasindi port of entry, according to the DRC health ministry. They are mostly informal traders, people visiting family and friends, or Congolese taking advantage of Uganda’s better equipped health services.

When TNH visited Kasindi earlier this year, dozens of people waiting to make the crossing were lined up to get their documents checked, while a hygiene official in a surgical mask screened them with an infrared thermo-gun. Those found to have higher-than-normal body temperatures were tested further for Ebola-like symptoms.

This screening station was just a simple wood and tarp gazebo, some plastic outdoor furniture, and a makeshift water tank for hand-washing.

But the increased surveillance at border crossing points has led to rising frustration over delays. There are a number of unofficial routes that can be used to avoid officialdom – these illegal backroads (known as ‘panya’ in the DRC) are favoured by smugglers.

In a statement on Tuesday, Uganda’s health ministry called on the public to “cooperate with immigration, health and security officials to ensure effective screening at all entry points.”

Robert Franco Centenary, an opposition legislator for Kasese municipality, said he was confident the government could contain the situation, but nonetheless sounded a note of caution.

“On a weekly basis, we interface with the Congolese people, especially on Tuesday and Friday, which are market days,” he told TNH. “I think the community should really take precautions. We know how Ebola is spread. These are things we can avoid. We need to avoid handshaking and being in congested places.”

Is this an international emergency?

Following news of the cases in Uganda, the WHO is to convene an emergency advisory committee as early as this week to review the situation and decide whether the outbreak now poses a global health threat.

“Committee members have been alerted and put on standby,” Jašarević told TNH.

If the WHO declares the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, or PHEIC, that would likely lead to travel and trade restrictions – measures that could complicate humanitarian operations if border crossings are closed or suspended.

The WHO decided – for a second time – on 12 April not to declare the Ebola situation in Congo a PHEIC, but is under increasing pressure to do so from some public health experts.

One concern if it does is that resulting border closures might increase the risk of transnational spread due to more people travelling illegally through porous borders.

oa-so/ag