A “third wave” of COVID-19 cases is filling hospital beds, exhausting oxygen stocks, and testing already overloaded health staff in the hardest-hit African countries.

Continent-wide, recorded infections are at over six million, with more than 153,000 official deaths. The highly transmissible Delta variant is now prevalent in 16 countries, and is surging through unvaccinated populations.

“The worst is yet to come,” Matshidiso Moeti, the World Health Organization’s regional director for Africa, has warned. “The end to this precipitous rise is still weeks away.”

The continent’s vaccine rollout is crawling, slowed in part by a critical shortage of doses. Countries are reliant on bilateral deals and the UN-backed COVAX facility, which aims to distribute vaccines equitably. But vaccine deliveries have not come close to matching needs, and almost ground to a halt in May and early June, according to the WHO.

As a result, less than two percent of Africans are fully vaccinated, and the 50 million jabs administered so far account for just 1.6 percent of the global total.

“Vaccine nationalism” – the hoarding of stock by Western governments – is part of the problem. But there have also been failings in the vaccine strategy of individual African countries – despite their proven ability to respond to other health emergencies, including HIV.

The ‘third wave’ by the numbers

The vaccine supply shortages could have been anticipated, rollouts could have been better managed, and the vaccine hesitancy emerging in several countries more effectively countered.

Instead, public health messages have struggled to ease public concerns, much of it fuelled by viral conspiracy-minded social media. Allegations of corruption, which have toppled at least one health minister, have further undermined public confidence in government responses.

COVID-19 is more than a health crisis. The lack of vaccines has left governments with few options other than painful lockdowns to try to slow the spread, deepening hardships. In South Africa, the worst-hit country on the continent, the draconian measures have seen a surge in job losses, with nearly half of South Africans now reporting they go to bed hungry.

The following takes the COVID-19 temperature in six countries. The snapshot ranges from vaccine-sceptical Burundi, to Uganda, where the government is struggling to get a grip on the fast-spreading Delta variant. Data on cases, deaths, and vaccinations, is sourced from Our World in Data.

Burundi: 'Let health professionals get vaccinated'

COVID cases: 5,706

Deaths: 8

Vaccinations: n/a

Percentage of population vaccinated: n/a

As some countries scramble to replenish their vaccine stocks, Burundi has taken a different path: opting out of the COVAX programme and holding back on approving vaccines, which the government says were produced in a hurry and are potentially unsafe.

Though more than 121 COVID-19 cases were recorded on a single day last month – the second highest recorded – the government maintains there is no cause for alarm and has eased quarantine and border restrictions in recent weeks.

Burundi took a lackadaisical approach when the pandemic first struck. Pre-election rallies drew thousands into jam-packed stadiums and WHO officials were declared personae non gratae. Things changed when a new president came to power following the sudden death of Pierre Nkurunziza to what many suspect was COVID-19: Mask wearing was made compulsory on public transport and night clubs and karaoke bars were closed.

In interviews with The New Humanitarian, frontline health workers expressed frustration in the government’s vaccination stance. One doctor at a private clinic said he travelled to a neighbouring country to get a vaccine that would enable him to work safely.

The doctor – who contracted COVID-19 last year – said he hoped the government would follow the lead of Tanzania, which has asked to join COVAX amid a pandemic policy shift following the March death of coronavirus-skeptic former president, John Magufuli.

“This is a big step because it will serve as a lesson for our government,” said the doctor, who asked not to be named. “I would advise the Burundian government to let health professionals get vaccinated. It would make them more stable and secure.”

Bujumbura paramedic Jean Marie, who did not want his surname published, said he would “feel safer” if vaccines were offered to health workers, while a nurse aide of 20 years who wanted to remain anonymous said they felt “insecure at work”.

Bus driver Adbul Karim was less fussed about getting jabbed: “If I try to see the situation, I don't see the importance of the vaccine,” he said. “Countries that have vaccinated almost all of their populations continue to be confined [so] my question is "how important is the coronavirus vaccine when even the vaccinated are under lockdown?"

The reporter’s name is being withheld for security reasons

Cameroon: 'A vaccine takes many years of trial and error for it to be tested and approved'

COVID cases: 80,858

Deaths: 1,324

Vaccinations: 163,921

Population vaccinated: 0.11 percent (fully), 0.40 percent (partly)

Be it AstraZeneca or Sinopharm, Cameroonians seem doubtful over the efficacy of the vaccines being offered by the government. Less than 10 percent of the more than 800,000 people targeted for the first phase of vaccinations have been jabbed since the launch of the campaign in April. A parliamentarian has gone so far as to suggest vaccines should be sneaked into bottled water to overcome the hesitancy.

That hasn’t done much good for public confidence – even among some doctors. One general practitioner, who asked for anonymity, said his concern was the speed of vaccine development: “A vaccine takes many years of trial and error for it to be tested and approved for use.”

The only reason Festus (he didn’t want to give his full name) said he consented to being jabbed last month was because the organisation he worked for as a driver threatened to sack those who refused. With just a few years to go before retirement, “I had no choice”, he said.

The government’s public awareness campaign has failed to address concerns and debunk the mushrooming conspiracy theories. Public cynicism has also deepened over reports of official corruption. Half the cabinet – 15 ministers, including health boss Manaouda Malachi – are being investigated over the disappearance of most of a $335 million loan from the International Monetary Fund to support the anti-COVID fight.

Emeline Fonyuy, Yaoundé, Cameroon

Mali: Third wave passes

COVID cases: 14,486

Deaths: 528

Vaccinations: 196,862

Population vaccinated: 0.26 percent (fully), 0.46 percent (partly)

Mali has already passed the peak of its third wave, which saw more cases than the previous two, Akory Ag Iknan, the director of the country’s National Institute of Public Health, told The New Humanitarian. Daily cases reached more than 400 in early April but have since tailed off.

More than 190,000 people have, meanwhile, received their first vaccine dose after a COVAX shipment in March. The rollout is focused on the capital city, Bamako, but Iknan said some supplies have been made available in northern and central parts of the country, where jihadist groups and communal militias are active.

Negative publicity and mixed messages about the vaccines have hindered the rollout. Amid low uptake, some 100,000 doses were donated ahead of expiration to neighbouring Côte d'Ivoire, though a new COVAX batch is expected to arrive in August.

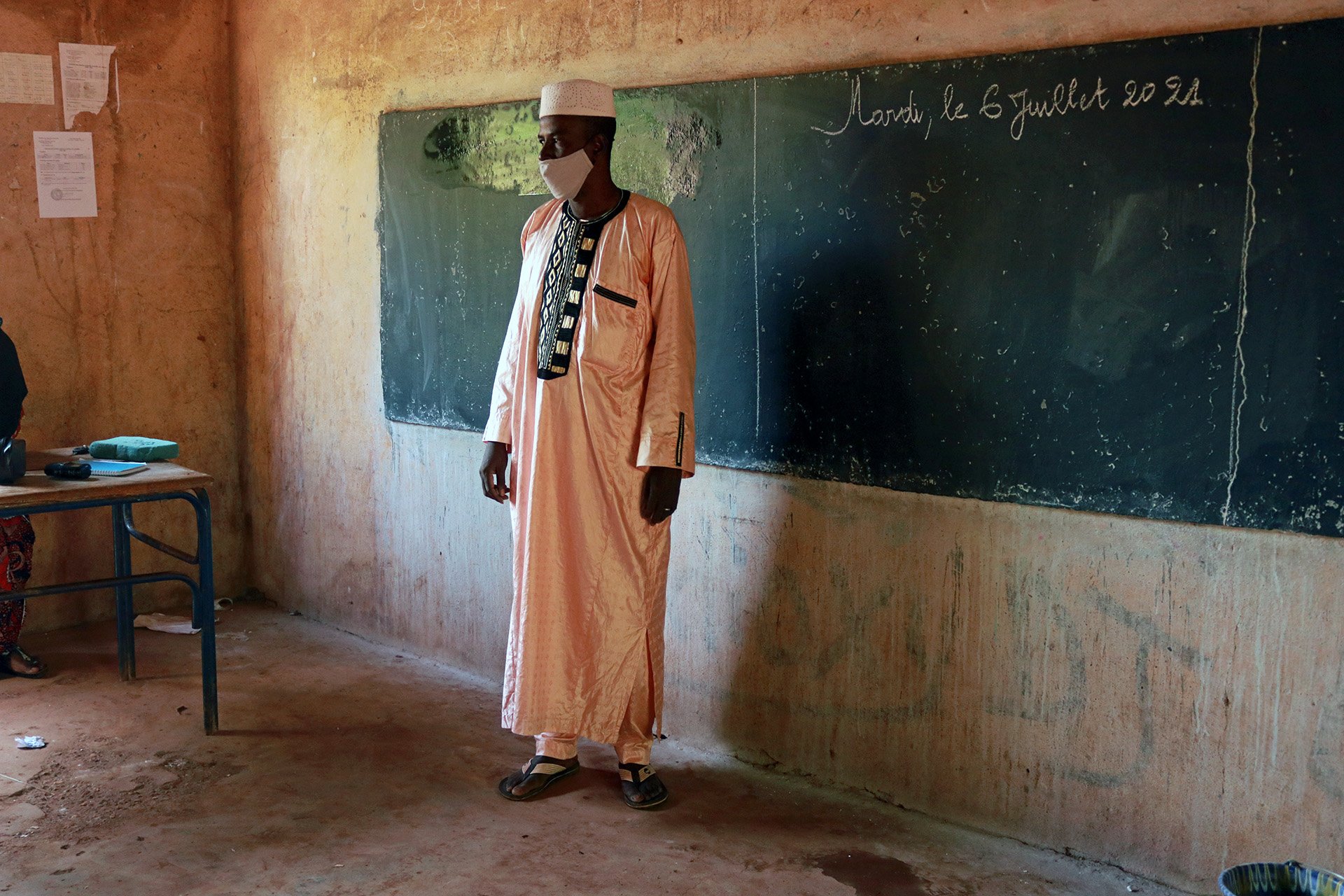

At a bustling Bamako school visited by The New Humanitarian last week just two out of 200 teachers had opted to take the vaccine, according to the school’s director, Mahamadou Assalia. And at a nearby vaccination site within a community health centre, expatriate workers were the main group receiving jabs on a recent afternoon.

Mamadou Tapily, Bamako, Mali

Nigeria: Virus fatigue, vaccine disinformation

COVID cases: 168,867

Deaths: 2,125

Vaccinations: 3,938,945

Population vaccinated: 0.68 percent (fully), 0.55 percent (partly)

For many Nigerians, COVID-19 exhaustion is beginning to set in. While banks, airports, and a few malls still insist on face masks, they've been discarded at markets and on public transport on the assumption (or at least the hope) that the coronavirus is in retreat.

Part of the issue is numbers. With a population of 200 million, the official infection rate seems miniscule. In central Kogi State, where the governor has denied the existence of COVID-19 and opposes vaccinations, only five cases have been reported. But Nigeria’s puny testing capacity has missed what antibody surveys have revealed: In some parts of the country a fifth of people could have been infected with the virus.

Nigeria has received just one shipment of four million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine via the COVAX facility. In common with most countries, a limited rollout has prioritised health workers and the vulnerable. New supplies are being negotiated by the government to help reach the general population.

Here, disinformation is proving one of the biggest obstacles. The latest viral TikTok is of a man claiming his vaccine jab electrified his arm. "As ridiculous as this and other conspiracy theories are, vulnerable people believe them and are therefore continuing to take the risk of avoiding COVID-19 vaccination,” Faisal Shuaib, head of the National Primary Health Care Development Agency, said at a press conference last week.

Dulue Mbachu, Abuja, Nigeria

South Africa: Policy blunders and a 'vaccine quagmire'

COVID cases: 2,206,781

Deaths: 65,142

Vaccinations: 4,236,718

Population vaccinated: 2.5 percent (fully), 4.28 percent (partly)

A rise in COVID cases, centred on the commercial hub of Gauteng, is straining South Africa’s already overburdened health service. Hospitalisations are expected to crest only by the end of the month.

The severity of the third wave has exposed a series of policy blunders that cumulatively have created what the country’s most prominent COVID-19 scientists have described as a “vaccine quagmire” – where a lack of a coherent strategy has left the country essentially unvaccinated, reliant on painful lockdowns to slow each new wave.

“[Around] five percent [of South Africans] are vaccinated,” virologist Francois Venter, one of the scientists critical of the government’s approach, told The New Humanitarian. “The surge of vaccinations we have seen in the last three or four weeks is not going to do diddly squat for the third wave.”

South Africa is administering about 170,000 vaccinations a day, short of its 300,000-a-day target, but the pace is picking up. It has managed to inoculate 480,000 health workers and 40 percent of those aged over 60. It has now extended the programme to the over-35s.

But with a slow rollout and a fast-mutating virus, the vaccine is not a cure-all. Physiotherapist Kayla Majiet was among the frontline health workers vaccinated in March, but the initial “peace of mind” she felt has since waned. A “few” vaccinated colleagues in the private hospital where she works are still getting sick, “and that has changed my confidence in the vaccine. It feels the same as before.”

Guy Oliver, Cape Town, South Africa

Uganda: 'Patients who need treatment are not reaching us'

COVID cases: 88,194

Deaths: 2,164

Vaccinations: 1,058,084

Population vaccinated: 0.01 percent (fully), 1.16 percent (partly)

There has been a jump in hospitalisations – roughly 10 times higher than in May – as a result of the Delta variant. Cases in Uganda aren’t expected to peak until late July or early August, but there’s already a critical lack of oxygen and hospital beds.

The shortages extend to PPE. “It’s a very big challenge. There’s very few [PPE kits],” said one nurse working in an intensive care unit in the capital, Kampala. “At times you even use a mask for a week. If you don’t have the money to buy for yourself, then it becomes hard,” added the nurse, who asked that her name not be used.

The government announced a partial lockdown in June as cases began to rise. A two-month jail sentence has been imposed for flouting regulations, which include the mandatory wearing of face masks in public. “The patients [who need treatment] are not reaching us [as a result of the lockdown], and we are struggling in terms of [equipment] resources,” said Mukuzi Muhereza, the secretary-general of the Uganda Medical Association.

Uganda has so far received 1.1 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine through the COVAX facility. Almost a million more doses are expected by August, as well as a donation of 300,000 doses of China’s Sinovac vaccine. The government’s goal is to jab just under 22 million people over three years – roughly half the population. “The biggest problem now is unavailability of the vaccine,” said Muhereza. “We have countrywide stockouts and those eligible can’t get vaccinated.”

Refugees fall under the government’s vaccination plans. Uganda is sheltering 1.4 million people who have fled the region’s wars, the largest refugee population in Africa. So far, just under 4,000 have been inoculated, and the programme has been paused. “We call on the international community to help Uganda increase access to COVID-19 vaccines and protect the lives of refugees and the communities hosting them,” said Rocco Nuri, a spokesperson for UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency.

Samuel Okiror, Kampala, Uganda

Edited by Obi Anyadike and Philip Kleinfeld.