Sitting on a bench in the seaside town of Hendaye, France, just across the border from Spain, Natasha* pulled a baseball cap low over her forehead, sinking into her seat as if she could become part of the furniture.

She didn't notice the grey station wagon until it was already stopped and two men with orange “POLICE” armbands had stepped out, asking for papers she didn't have.

In her 20s from Côte d'Ivoire, Natasha had recently arrived in Europe after crossing the Mediterranean Sea by boat. But less than 20 minutes after taking a short bus ride across the invisible line dividing France from Spain, she was bundled into a French police car, dropped off at the border, and told to go back to Spain.

The scene is a common one at this border and several others in the Schengen Area: a zone of 27 European countries where – on paper at least – passport and border controls have been abolished.

The reality for many people, especially migrants and asylum seekers, is starkly different. France is one of six member countries – along with Austria, Denmark, Germany, Norway, and Sweden – that have used emergency provisions in the Schengen agreement to reintroduce border controls in recent years, citing the threat of terrorism and irregular migration.

Legal experts, human rights advocates, and local activists who spoke with the New Humanitarian said these controls are applied selectively to people based on the colour of their skin and aim to prevent asylum seekers and migrants from passing from one EU country to the next. As a result, they added, they are pushed to take more dangerous – sometimes deadly – routes to cross internal EU borders, adding more suffering and trauma to already long and difficult journeys.

“There are no borders, except for Black people and Arabs,” said Ion Aranguren, a member of Irungo Harrera Sarea, a civil society organisation that provides support to asylum seekers and migrants in Irun, Spain, across the border from Hendaye.

According to the EU’s Dublin Regulation, asylum seekers are supposed to apply for protection in the first member state they enter. Many people, however, want to continue on to other EU countries where they have family members and friends, already speak the language, or where support services are more robust and the economy is stronger.

Those who submit a claim in a different EU country can end up being sent back to the first country they entered. But the Dublin Regulation sets out a specific process – as well as exemptions – for these returns.

“Whether it’s in train stations, at toll booths, or on walking trails, the controls which are conducted are clearly discriminatory,” said Laure Palun, director of Anafé, a coalition of French civil society organisations that has documented racial profiling in Hendaye and elsewhere along the French border. “The people who are checked are those who are racialised.”

The French Ministry of Interior, which is responsible for the border police, did not respond to a request for comment.

‘If you’re alone and you’re Black, they’ll check you’

A commuter railway connects Hendaye to Irun, rolling seamlessly across the border. At the station in Hendaye, and throughout the surrounding area, French police regularly stop people to check identity papers, sending asylum seekers and migrants they find back to Spain.

On a recent afternoon, two young Black men stepped off the train and walked to a nearby bus stop. French police walked up to them immediately. They were the only people checked out of dozens of passengers – all of the rest of them white – who disembarked. The police left after the two men showed they had the necessary papers.

This happens almost every day, said one of the men, a 19-year-old Spanish resident who crosses the border to go to school.

If he is travelling with white passengers, the man – who asked to remain anonymous – said police wait until he’s no longer with the group to approach. “If you’re alone and you’re Black, they’ll check you,” he said. “At a certain point, you just have to get used to it because that’s just how it is.”

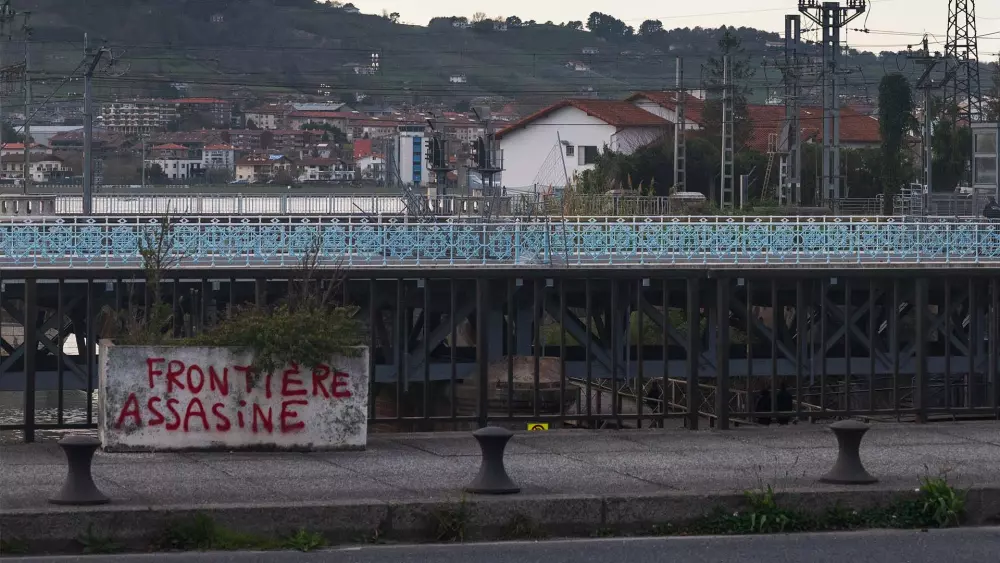

Right: A man from Bangladesh gazes across the Bidasoa river, which divides Spain and France, near the Spanish town of Irun in March. Left: Graffiti reading "border kills" on the cross-border bridge that connects Spain to France. French police have closed the blue pedestrian bridge in the background since 2021. Photos by Riley Sparks/TNH.

Humanitarian organisations have extensively documented similar racial profiling during checks by French police on trains arriving from Italy as well, and the practice was noted as far back as five years ago in a report by the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights, a French government body.

In response to the report’s allegations, French border police told the commission that officers avoid racial profiling by checking each train passenger – a claim contradicted by many first-hand accounts, the commission noted.

Across the border in Irun, Tarek, 20, from Sudan, laughed and shrugged his shoulders as he exited the bridge from France. His second attempt at crossing in two days had once again ended in the back of a police car. His travelling companion, Clara*, 28, from Guinea, was waiting for him on a park bench. He had been caught and sent back hours earlier.

“No luck today,” said Tarek, who asked to be identified by his first name only. He had arrived in Irun a few days before, at what he hoped would be the last border he would cross after five years on the road. His journey had included a year and a half in Mauritania, where he worked in construction and saved up enough to continue on to Morocco, then to the Canary Islands by boat. Other passengers died making the crossing, Tarek said.

He was one of about 10 people sent back from France to Spain over a 90-minute period when The New Humanitarian visited Irun.

After being sent back, some people opt for riskier paths than trying their luck on the trains and buses, including swimming across the Bidasoa river, which runs along the border, or walking along train tracks into France.

Over the past two years, at least 11 asylum seekers and migrants have died trying these routes. A twelfth person, a young man from Eritrea, died by suicide near the river in 2021.

Along the French-Italian border – where police conduct similar checks – at least 34 people have died since 2016 walking on the highway or through the mountains near the border town of Ventimiglia, Italy. The most recent death was in January, when a man’s body was found on top of a cross-border train.

‘At every stage, there are illegalities’

The borderless Schengen zone is one of the signature achievements of modern Europe. Member countries are allowed to temporarily reintroduce border controls for up to six months in emergencies, like France did after the November 2015 terror attacks in Paris.

But since late 2015 or early 2016, Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden, have all been renewing those temporary controls every six months – keeping them in place for the past seven years.

In 2022, in a case focusing on the Austria-Slovenia border, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) – the EU’s supreme court – ruled that the practice was unlawful. After the initial six-month period, the court said, countries should be able to find a more permanent solution to handle the emergency while keeping borders open. But enforcing the judgement would require action from the EU’s executive branch, the European Commission, which has so far not intervened.

The European Commission did not respond to The New Humanitarian’s request for comment.

The returns carried out by police at borders like the one between Irun and Handaye are also legally questionable. Instead of following official procedures laid out in the Dublin Regulation, police are “using the idea of Dublin” to return asylum seekers and migrants at internal EU borders, according to Iker Barbero, a professor at the University of the Basque Country in Leioa, Spain who has researched police practices in Hendaye and Irun.

“[Dublin] cannot be an excuse to immediately return people,” he said.

“In every case, at every stage, there are illegalities,” said Palun, from Anafé. “The re-establishment of controls is illegal in terms of European law. The resulting controls are illegal. And all of the procedures which flow from that will be illegal as well.”

‘It’s a dehumanising experience’

In other countries that have reintroduced controls, similar returns and profiling happen regularly as well.

Lawyers with the refugee advocacy organisation Pro Asyl are working on two recent cases of people who were sent back from Germany to Poland after asking for asylum. In both cases, they had experienced violence in Poland and should not have been sent back without an assessment of their cases, according to Karl Kopp, head of Pro Asyl’s Europe department.

“You really see it, especially with the young boys who left their countries with a lot of hope to provide for their families. This hope is being dismantled, little by little, piece by piece.”

“The barriers to control and to reject and push back people are not in line with Schengen, and not in line with European legislation,” Kopp told The New Humanitarian.

Swedish border police are also accused of racial profiling. One Black resident of Malmö, Sweden, who crosses daily to work in Denmark, told Swedish broadcaster SVT he had been “randomly searched” 150 times in 18 months at a border checkpoint on the Øresund Bridge.

At the France-Italy border, the reintroduction of controls means people end up getting stuck in difficult living conditions in border towns for anywhere from a couple of days to several weeks, crossing and being sent back repeatedly, before finally making it through.

In 2022, about 33,000 people passed through Ventimiglia and Oulx – the main towns on the route – according to estimates by the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), which provides housing and support for some asylum seekers and migrants. Since Ventimiglia’s largest migrant shelter closed in 2020, most people waiting to cross sleep under a bridge.

Read more: Purgatory on the Riviera

“It’s a dehumanising experience,” said Francesca Pisano, a programme coordinator with DRC in Italy. “You really see it, especially with the young boys who left their countries with a lot of hope to provide for their families,” she added. “This hope is being dismantled, little by little, piece by piece.”

Women who have passed through Libya – one of the main departure locations for asylum seekers and migrants trying to reach Europe – have often suffered sexual violence. Many arrive in Italy with babies. “Their mental state is shattered,” Pisano added.

Without access to medical care en route, many people arrive with out-of-control chronic conditions or with infections and advanced cases of scabies, according to Cecilia Momi, a humanitarian affairs officer with Médecins Sans Frontières Italy.

But access to basic necessities – not to mention healthcare or psychological support – is limited in the border towns where people get stuck. “With pregnant women, we tell them, ‘You have to drink a lot if you have vertigo and nausea’. And they tell us, ‘Water is expensive,’” Momi said.

‘Sometimes you have to take risks to live’

Back in Irun, after being sent back from France, Tarek – the Sudanese asylum seeker – and his friends were approached twice by men who offered to drive them over the border for between €50 and €100 per person – prices Tarek and the others rejected as too expensive.

Within a couple of days, most of the members of the group would make it to France – one way or another.

Later, on the riverbank near a memorial to people who have drowned trying to swim to Hendaye, one of the would-be smugglers told The New Humanitarian that bringing people across by road is easy – and much safer.

“The water is too deep. If someone doesn't know how to swim, there's no way they'll make it,” said the man, who himself had crossed the Mediterranean to reach Europe. People will keep trying, he added: “Sometimes you have to take risks to live.”

Before Natasha crossed into France and was sent back, The New Humanitarian met her in the town square in Irun. Talking about her experiences, she pointed to burns on her arms, caused by boat fuel mixing with Mediterranean seawater. “You have no idea what we’re fleeing, what drives us to the sea. We don’t even know how to swim,” she said.

“We enter France like we’re criminals, like we’ve done something wrong,” she continued. “If no one brings forward a solution, we’ll continue to risk our lives.”

*Pseudonyms used to protect the identities of asylum seekers and migrants.

Edited by Eric Reidy.