During 14 years of civil war in Liberia, its citizens were victims of mass killings, rape, torture, displacement, and other human rights violations. In spite of growing international calls for the creation of a war crimes court, the country hasn’t prosecuted anyone for those atrocities. The only significant Liberian government-sponsored mechanism for justice is a community-led effort known as the “palaver hut” programme.

Under this model, victims and alleged perpetrators are given the space for truth telling as a means to establish a common ground for peace and reconciliation. The programme is restricted to violations classified as “lesser in gravity” such as arson, assault, forced displacement, forced labour, looting, destruction and theft of properties, and desecration of sacred places.

In August, 18 years after the war ended, Leemu*, a farmer and trader in her 40s, attended a public palaver hut hearing at the town hall in Sanoyea, north of the country’s capital, Monrovia, to face the former fighter she had accused of committing crimes against her and her family.

At one end of the town hall sat elders from the community, along with representatives from Liberia’s Independent National Commission on Human Rights (INCHR). Peter*, the accused, also sat in the room.

“When Peter and other fighters entered our town, they beat people, looted, and drove us from there,” Leemu told The New Humanitarian. “When we ran away, I had to leave my grandmother behind because she was too old to walk and I was not able to carry her on my back. One night, the roof fell in and she died because no one was there to help her.”

Her trauma did not end with the war. Like many fighters, Peter returned to the community where Leemu would see him.

“The hearings are good for the community. People came and spoke their minds and forgave each other.”

“I remember Peter's face from when he and the other fighters drove us from the town,” Leemu said. “After the war, I used to see him sometimes in the area, and I used to feel bad because it is because of him I wasn't there for my grandmother.”

During the hearings, Peter pleaded guilty and asked for forgiveness, though he claimed to have acted on the order of his commander under the threat of punishment. Besides his apology and the public hearing, he faced no legal punishment for his acts during the war. He left town before he could be contacted for comment.

“The hearings are good for the community. People came and spoke their minds and forgave each other,” said Moses Nupolu, the paramount chief of Sanoyea chiefdom who served on the seven-member committee for Leemu’s palaver hut. “Now the hearings are over, everyone is moving together in peace,” he added.

While human rights advocates agree that the palaver huts are a good mechanism for dealing with communal issues, they say they fall short.

“The hearings, by themselves, do not address the grave human rights atrocities committed during the war as cases like massacres cannot be addressed in the palaver hut,” said Tennen Dalieh Tehoungue, a Liberian researcher on universal jurisdiction and transitional justice, and a PhD candidate at Dublin City University.

Politically protected war criminals

The question of accountability for war crimes still looms large over Liberian society – a fact US Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice Beth Van Schaack underscored during a visit to the country earlier this month. “There has been no accountability here on the criminal side, or the civil side, for those who have been most responsible for those abuses,” she said.

Between 1995 and 2003, Liberia was convulsed by two civil wars that left at least 250,000 people dead, and millions displaced. Two years after the end of the war, the Liberian Transitional Legislative Assembly established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Its mandate was to promote “national peace, security, unity and reconciliation” by investigating gross human rights violations, violations of humanitarian law, sexual violations, and economic crimes that had occurred during the armed conflicts.

In 2009, the commission issued recommendations to the government, including reparations, an extraordinary criminal tribunal, domestic prosecution, public sanctions, and a national palaver hut programme.

“There has been no accountability here on the criminal side, or the civil side, for those who have been most responsible for those abuses.”

However, many recommendations – including prosecuting and disbarring war criminals from public office – were never implemented.

Notably, the commission recommended that Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the president at the time, be disbarred from public office because of an alleged connection with one-time rebel leader and former president Charles Taylor. But in 2011, the Liberian Supreme Court held that recommendations barring a number of people from holding public office were unconstitutional.

“The TRC report engenders little political will because those listed in the report as [the] most notorious perpetrators hold influential positions in government,” said Aaron Weah, an adjunct lecturer at the Kofi Annan Institute for Conflict Transformation (KAICT) and a PhD candidate in transitional justice at Ulster University. “Secondly, it appears that the formula for winning the presidency in Liberia requires presidential candidates to court perpetrators who are gatekeepers to certain vote-rich counties.”

Human rights groups have repeatedly called for the establishment of a war crimes court to more effectively hold individuals accountable for atrocities. But officials have refused to establish one, and the presence of former war actors in the political establishment has made that goal much more difficult.

For example, former warlord Prince Johnson, who was recommended for debarment from public office, is currently a two-term senator of vote-rich Nimba County, and an ally of current President George Weah. He has opposed a war crimes court, and promised to campaign against any presidential candidate who commits to setting one up.

“Unless heads of warring factions are arrested, tried, and convicted for war crimes, the message of deterrence to prevent another circle of violence will never truly be communicated.”

Instead, litigation against notable war actors and former warlords has been left to foreign countries such as the United States, Britain, Finland, and Switzerland – operating under the legal principle of universal jurisdiction.

A former Liberian rebel recently went on trial in France, accused of crimes against humanity, torture, and acts of barbarism during the armed conflict. Others have been tried on fraud charges for omitting their roles in the war from immigration documents.

Weah, the lecturer, said such litigation has “sustained the momentum for criminal accountability” in Liberia.

“However, so far, all of those arrested in Europe and America have been largely junior level perpetrators,” he said. “No head of a warring faction has been arrested, tried, and convicted, except Charles Taylor, through the Sierra Leonean Special Court.”

Liberia, he noted, has been turned into a “haven for war criminals. Unless heads of warring factions are arrested, tried, and convicted for war crimes, the message of deterrence to prevent another circle of violence will never truly be communicated to the [next] generation.”

A space to heal

In spite of its limitations – and the broader failure to bring higher-level war criminals to justice – the palaver programme has brought a modicum of justice to traumatised communities.

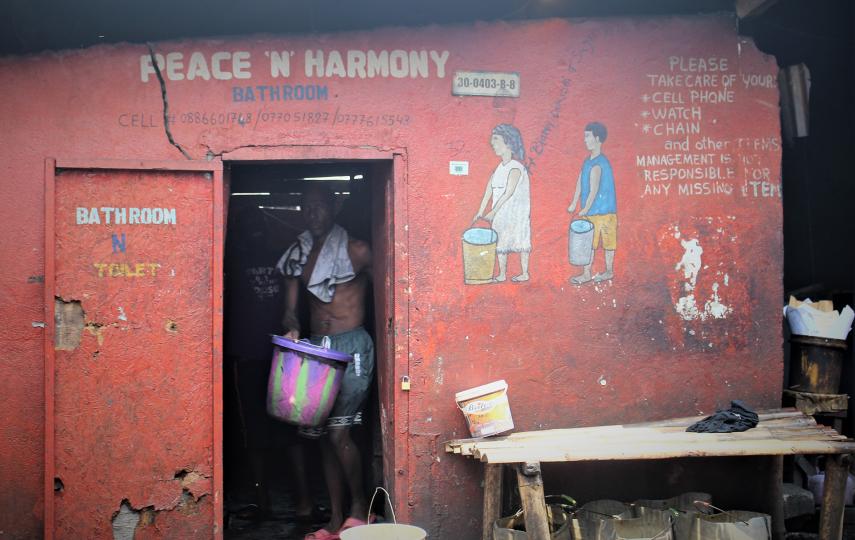

Based on age-old tradition, Liberians have long used the system to settle disputes. The practice is common in rural areas, and hearings are usually convened by community leaders to settle disputes involving family issues, land, debt, or theft.

Tehoungue said palaver hut hearings can be effective when legitimate leaders mitigate conflict between victims and perpetrators. “These exchanges allow for mutual understanding and a ‘safe space’ for victims to demand accountability and compensation,” she said.

The Liberian government launched the National Palaver Hut Programme in 2013, with the aim of boosting reconciliatory efforts. The process is overseen by a council of elders who are mostly community leaders; it usually ends with the perpetrators apologising to their victims.

Joseph Blamiyon, who coordinates the programme for the INCHR, said community leaders “listen to stories and facilitate resolution of the case”. To address the possibility of individuals potentially being re-traumatised, he said the INCHR had contracted psycho-social services to provide mental health assistance during and after the hearings.

Thus far, the programme has held hearings in four counties and helped resolve at least 277 war-related cases involving more than 500 people, giving some more closure to victims and providing a safe space for people, families, and communities.

Since the hearings aren’t legally binding proceedings, cases can be dismissed if the accused deny the accusation and if the committee has no evidence of the alleged act.

While the implementation of other justice mechanisms in Liberia remain uncertain, the palaver hut can be a space for healing, for some victims at least.

Princess*, who faced a fighter she accused of war crimes during the palaver hut hearings in Sanoyea, said she felt some closure afterwards. “The war is over. The man has apologised, and I have forgiven him,” said the trader. “I have moved on. It is no longer in my mind.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of victims and perpetrators.

Edited by Cristian Salazar.