Cash shortages, sporadic access, and pressure on frontline staff are squeezing aid to hundreds of thousands of people in Myanmar’s remote conflict zones, humanitarian groups say, as the fallout from the country’s military coup builds.

Myanmar has been largely paralysed since the military seized power in a 1 February coup, ousting de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi and the elected government. Security forces killed at least 18 protesters on Sunday in the bloodiest day since anti-coup demonstrations erupted in cities and towns across the country; authorities have arrested at least 1,200 people over the last month.

Frontline aid groups say they’re running low on cash as the protests have effectively shut down Myanmar’s banking sector, making it difficult to transfer money into or around the country. Some groups have been able to send limited amounts through mobile or online transfers, or get small amounts of money from ATMs.

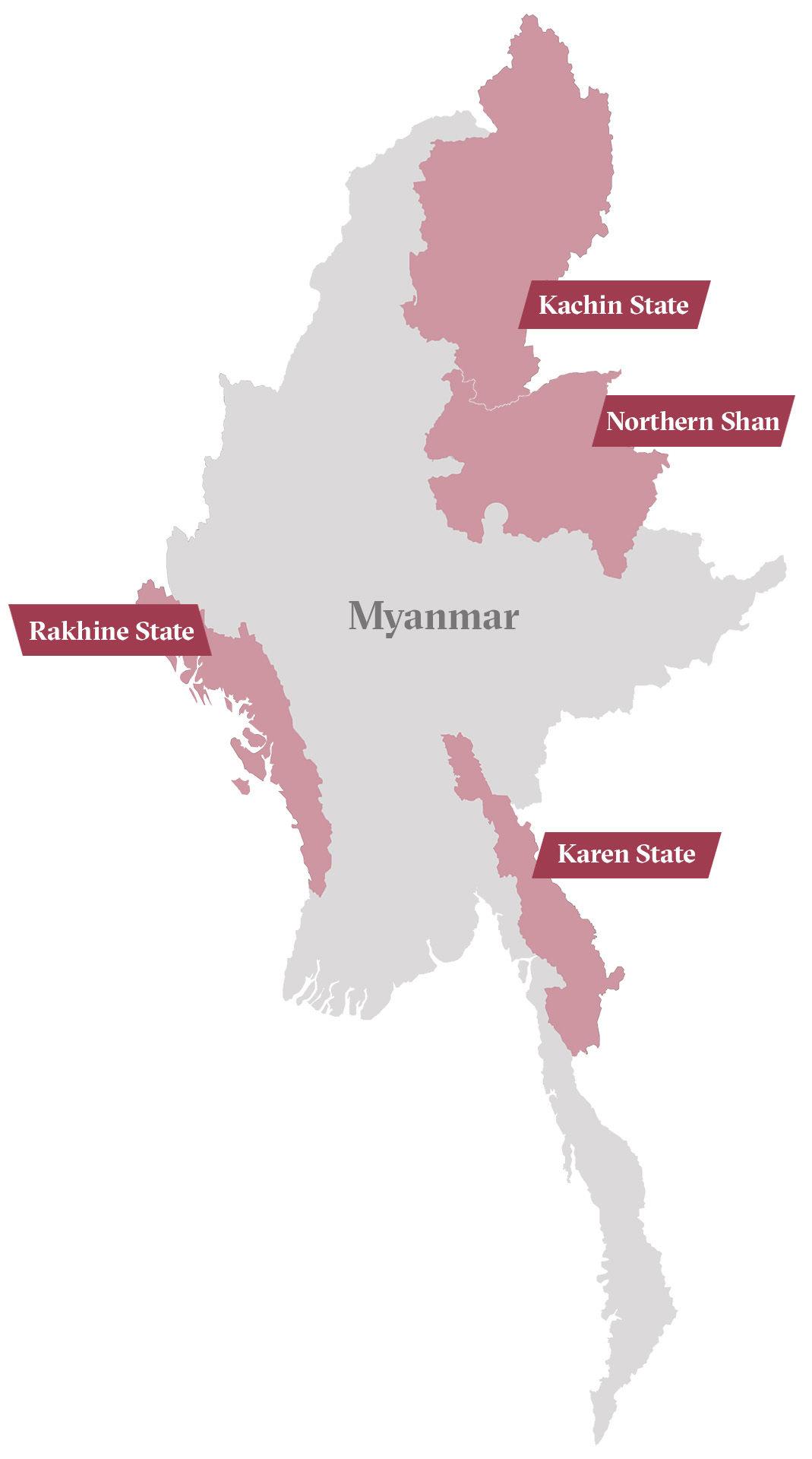

“Many of us cannot operate,” said an aid worker with a local humanitarian group in northern Myanmar, where some 100,000 people are displaced in conflicts in Kachin and northern Shan states, and many depend heavily on cash aid. “So for the IDPs themselves, one thing that is an immediate worry is food.”

Before the coup, nearly one million people relied on humanitarian aid across Myanmar. This includes some 330,000 displaced in the country’s conflict zones, where ethnic armed organisations have battled the military or each other in long-running wars. Fresh clashes have displaced more than 3,000 more people in Myanmar’s north and southeast since the start of February, according to local groups and the UN.

Many international aid groups that suspended operations after the coup have resumed work, but they’re still dependent on erratic approvals from government authorities. Local groups don’t rely on government authorisation, but they’re severely limited by the cash shortages, new fighting, or the fear of being swept up in security crackdowns.

Some worry authorities will soon set their sights on these local civil society groups – many of whom are heavily involved in both humanitarian aid and activism, particularly in multicultural Myanmar’s ethnic areas. Many of these organisations have kept a low profile since the coup began, and officials with international aid groups told The New Humanitarian that some local staff have also gone into hiding.

“A lot of civil society and humanitarian actors are very concerned about their security,” said an aid worker with a local humanitarian group in Rakhine State, in Myanmar’s west, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals. “They have no idea what will happen tomorrow. Developments are unpredictable.”

New fighting, old restrictions

Aid to Myanmmar’s conflict hotspots was sporadic even before the coup, and humanitarian access continues to be volatile weeks later.

In the southeast, some 6,000 people have been displaced in clashes between the military and the Karen National Liberation Army since December. This includes 1,000 in the last month, said Naw Wah Ku Shee of the Karen Peace Support Network, whose members’ work includes cross-border aid operations from Thailand.

“They had to leave behind everything,” she said. “They had to flee, run for their lives, and hide in the jungle.”

The coup hasn’t yet directly affected operations here, aid workers said, because the displaced were mostly dependent on groups working along the Thai border. Some 91,000 people also live in refugee camps in Thailand, and international aid for refugees and internally displaced has dwindled over the last decade.

In northern Shan State, nearly 2,300 people have been uprooted in fighting between armed groups and the military since January, according to the UN.

In most displacement camps in Kachin and northern Shan, local aid groups already delivered monthly cash aid payments before the coup began. “But some of the IDPs have not yet received the cash transfers,” said the aid worker in northern Myanmar. “A few camps are still left, so they are quite worried.”

“They have no idea what will happen tomorrow. Developments are unpredictable.”

In northern Rakhine State, access has marginally increased since the start of the coup, several international aid workers told TNH. Myanmar’s military is accused of committing genocide against the north’s Rohingya population, including the purge of some 700,000 people to Bangladesh in 2017.

“We have more access than we had a month ago,” said one aid worker at an international NGO, who asked not to be named in order to speak freely. ”We’ve gone up to where we were in January, but that’s not to an acceptable level of humanitarian access.”

But access to at least 100,000 people displaced by the separate conflict between the military and the Arakan Army in other parts of Rakhine and neighbouring Chin State is “a big black hole” for some, the international aid worker said. Until a recent unofficial ceasefire, it was one of the country’s most heated conflicts.

Some of the displaced received three months’ worth of supplies before the coup, said the aid worker with the Rakhine humanitarian organisation, but “others don’t get any help”.

“Living conditions are bad,” they said. “It’s overcrowded and there are no proper [water and toilet] systems.”

Food prices rising, supply routes squeezed

Humanitarians worry cash shortages could spiral into a larger problem as funds drain in the coming weeks.

“We haven’t got any funds into the country since the first of February,” said the international aid worker. “It will start to become a bigger problem very quickly. I know of quite substantial organisations that have not managed to pay salaries in February.”

Another aid worker with a separate international organisation said there could be difficulties meeting payroll by next month.

Food and commodity prices are also rising, making it harder for people to buy what they need with what money they have.

Saw Htoo Klei, director of the Karen Office of Relief and Development (KORD), said border-based groups like his don’t rely on Myanmar’s banking sector so they have been able to continue cash aid to the newly displaced in southeast Myanmar.

“They had to flee, run for their lives, and hide in the jungle.”

But he worries food supplies will run low in the coming months, as people haven’t been able to cultivate fields for this year’s crops.

“They are not able to prepare for their next crop” because the military has shelled villages and fields, he said. “They don’t feel safe in their villages, and they don’t feel safe to farm.”

Food and income were already under pressure in parts of Kachin State controlled by the Kachin Independence Organisation, whose armed wing has clashed with Myanmar’s military for the last decade. KIO-controlled areas are home to about 40 percent of northern Myanmar’s 100,000 displaced.

The northeast border with China, the main supply route to KIO-controlled areas, has mostly been shut through the coronavirus pandemic. Local humanitarian groups have tried to bring supplies and aid from government-controlled parts of Myanmar, but this will become more difficult with the coup, said the local aid worker in northern Myanmar.

People in camps in government-controlled parts of the state are also starting to move to areas run by the KIO – potentially creating greater needs in areas most aid groups can’t reach.

“If this situation continues, humanitarian assistance in the KIO-controlled area will suffer a lot from this,” the aid worker said.

Closer scrutiny

Local humanitarians say they’re bracing for more pressure – and closer scrutiny – from the military.

“For the time-being, the military needs to pay more attention to the demonstrations,” said the aid worker in northern Myanmar. “However, I think it will soon come to humanitarian organisations, including international actors and civil society. What we can assume is it’s not far away: A lot of restrictions could be put on us, also.”

The aid worker in Rakhine State said local civil society groups have already been approached by both security forces and the Arakan Army – until recently at war but now in an uneasy ceasefire – and asked to not participate in anti-coup demonstrations.

“It’s not far away: A lot of restrictions could be put on us, also.”

The Arakan Army “said that they are building trust with Myanmar’s military, so CSOs (civil society organisations) should not hurt their relationship-building”, said the local aid worker.

There have been few public protests against the coup in Rakhine State; the military has released prominent ethnic Rakhine activists detained under Suu Kyi’s government, and appointed a Rakhine politician to a “state administrative council” set up by the military.

At the same time, the military government announced on state television a crackdown on unregistered civil society groups, the aid worker said: “They’re going to check: Which organisations receive money, from where. Everyone is freaking out.”

il/ag