Facing a global pandemic but saddled with conflict and aid blockades, Myanmar’s rebel-controlled borderlands are bracing for the coronavirus with piecemeal containment plans and severely limited supplies.

Myanmar’s health system is one of the least developed in Asia, and aid groups fear it’s particularly unprepared for a pandemic that has infected more than 2.4 million people worldwide. But the situation is even more precarious in far-flung conflict zones controlled by a range of ethnic armed groups that have battled Myanmar’s military, or each other, for decades.

In areas beyond the reach of the government and of most international aid, some armed groups and their civil society counterparts are leading a patchwork response to the coronavirus. But testing is scarce, treatment options are basic, and there's little outside help available should a large outbreak emerge – especially in cramped displacement camps home to hundreds of thousands uprooted by violence.

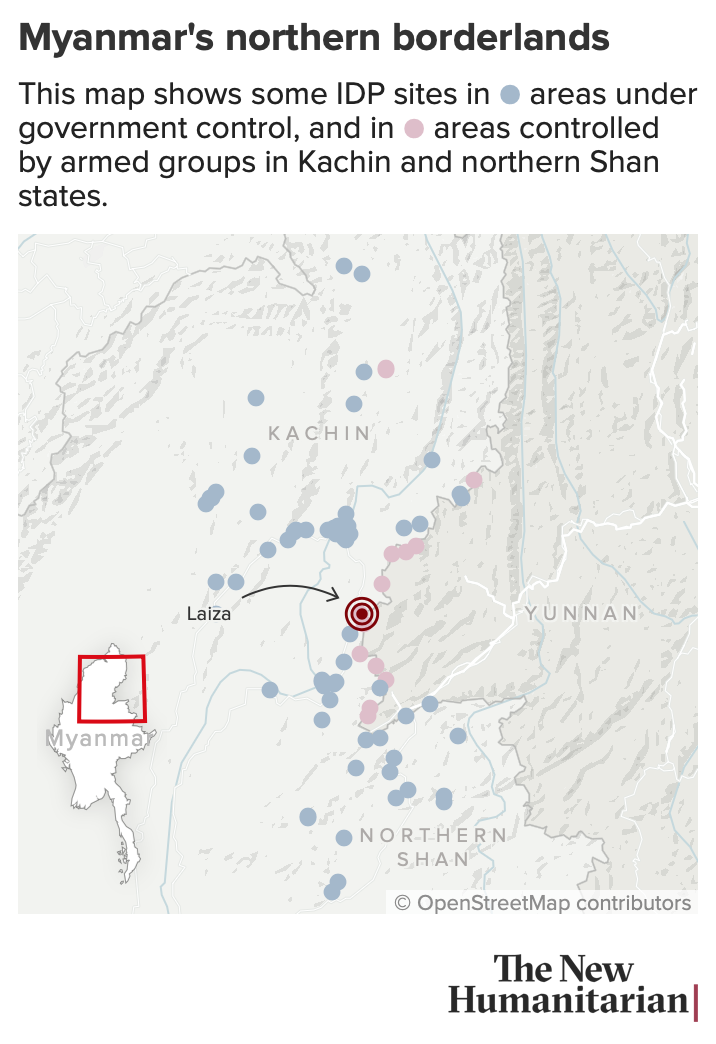

“The biggest concern that we have is, if the virus outbreak reaches and spreads among these populations who are living in crowded camps, we don’t have any preparation or necessary resources to respond and handle the virus outbreak,” said Gum Sha Awng, head of the Joint Strategy Team (JST), a coordinating body established by nine local humanitarian groups in Kachin and northern Shan states in Myanmar’s north near China’s Yunnan Province.

Resources and planning vary greatly. In some territories, armed groups run what are essentially parallel governments with basic but functioning hospitals. Other areas are active conflict zones with shifting front lines far removed from healthcare.

“If the virus outbreak reaches and spreads among these populations who are living in crowded camps, we don’t have any preparation or necessary resources to respond.”

Some armed groups are procuring coronavirus test kits and building makeshift quarantine sites. Others are relying on imperfect temperature screening to weed out potential cases. Many are simply trying to instruct residents on hygiene and physical distancing.

“The best we can do right now is telling the public to prevent virus infection by washing hands, social distancing, and restricting their movement,” said Dr. Hing Wawm, a medical expert with the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO), the governing body of the Kachin Independence Army, one of Myanmar’s major ethnic armed groups.

In Wa, an autonomous region that also partly borders Yunnan and is controlled by the powerful United Wa State Army (UWSA), authorities in the de facto capital, Panghsang, are conducting temperature screenings and mandatory quarantines on cross-border travellers, said Aung Myint, a senior official with the armed group. The UWSA has signed a peace treaty with Myanmar’s government, but there are sporadic clashes with other armed groups.

“There is no particular testing for people, but after a 14-day quarantine we let people go if they are not sick,” Aung Myint said, adding that no suspected coronavirus cases have been found among more than 200 people quarantined. “We are also doing public awareness on how to prevent infections by washing hands or using masks.”

Myanmar recorded at least 119 coronavirus cases as of 20 April; there were no known cases reported in IDP camps or conflict areas, according to the UN.

Some groups have called for a ceasefire to prepare for the coronavirus, though military officials have rejected such proposals. On Monday, a World Health Organisation driver was killed while transporting coronavirus samples from Sittwe in western Myanmar’s Rakhine State. The government blamed the attack on fighters with the rebel Arakan Army, which denied involvement.

On the ground, local groups say they’re asking for help from international aid organisations while urging Myanmar’s government to lift restrictions that have severed official aid and supplies for years, fearing a wider food crisis caused by closed borders.

Parallel governments in rebel territory

Perched on a mountainous stretch of eastern Kachin straddling the Chinese border, the city of Laiza is the headquarters of the KIO. For residents here, the main authority and healthcare provider is not the government but the KIO and its army, which has waged war with Myanmar’s military since a long-held ceasefire collapsed in 2011.

-

Seven decades of conflict and displacement

- Home to 135 officially recognised ethnic groups, Myanmar has seen decades of insurgency since achieving independence from British rule in 1948.

- There are at least two dozen ethnic armed organisations in the country. Some groups run their own territories as de facto governments; others have just a few hundred fighters. Asia Foundation researchers have tracked active or latent conflict in more than a third of the country’s townships.

- Today, conflicts new and old have left at least 350,000 in displacement camps around Myanmar. Rights groups warn that these overcrowded camps are coronavirus “tinderboxes”.

- More than 107,000 people live in 172 displacement sites in Kachin and northern Shan; roughly 36 percent are in areas beyond government control.

- In Myanmar’s west, escalating conflict in parts of Rakhine and Chin states has displaced more than 100,000 people over the last year. Some 130,000 mostly Rohingya uprooted by previous violence live in dilapidated camps overseen by the government in central Rakhine.

- Fresh conflict has displaced at least 2,000 civilians in eastern Karen State since February. Uncounted are thousands more civilians temporarily displaced or forced to migrate by sporadic clashes among armed groups or Myanmar’s military.

The KIO set up a “COVID-19 Prevention Committee” to prepare for an outbreak in late March. The organisation said it obtained 500 coronavirus test kits from China and Singapore this month. Eight people were initially tested for the virus, but their results were negative, the committee said in a statement last week.

The KIO has also banned gatherings of more than 20 people, closed restaurants and food stalls, and suggested that local churches – the area is majority Christian – postpone services. It is also building three quarantine centres for people travelling from government-controlled areas. Photos posted on KIO-run media show the construction of basic shelters made from wood or bamboo under tin or tarpaulin roofs.

There are about 150 medical staff, all trained in China, working in hospitals in remote Laiza and other towns. But there’s still a shortage of trained staff and equipment – let alone quarantine facilities and isolation wards for a pandemic.

If or when people with COVID-19 symptoms emerge, the KIO’s medical expert, Hing Wawm, said hospitals will be in desperate need of protective equipment, ventilators, patient-monitoring devices, oxygen tanks, and X-ray machines. Laiza’s main hospital has just 100 beds for a population of 60,000 people, including displaced civilians.

Services are even more sparse for the roughly 40,000 people living in 24 displacement camps on KIO-controlled land. Clean water and proper sanitation is inadequate. Many camps have no health clinics. Where they do exist, there are shortages of medicine, supplies, and medical staff.

“We are very scared of virus infection spreading among us because we don’t even have enough medicines for normal sickness in the camps,” Tu Lum, a 52-year-old living in Hpunglum Yang camp near Laiza, told The New Humanitarian by phone. “Social distancing is impossible, as families live two feet away from each other, but there is nothing we can do without support from the outside world.”

Local groups like the Kachin Peace Network, a group that works with displaced people, are trying to help the camps prepare. The organisation has raised donations to buy 100,000 surgical masks for health workers and potential patients, said Khon Ja, the network’s coordinator.

“We don’t even have enough medicines for normal sickness in the camps.”

“We are doing what we can to respond to health emergencies that could claim lives,” she said.

But the equipment, facilities, and training needed to contain a pandemic are in short supply: “The medical support is not adequate,” Khon Ja said.

Aid restrictions and cross-border trainings

The problems are magnified by near-total restrictions on aid in rebel-controlled areas. Even at the best of times, tens of thousands of displaced civilians in Kachin and northern Shan don’t have enough food, healthcare, or shelter, aid groups say.

Local civil society groups have been the backbone of disaster and conflict response in Kachin since clashes re-ignited in 2011, but they say donor support and humanitarian access continues to shrink.

Since 2016, Myanmar’s civilian government and its influential military have largely blocked outside humanitarian aid to displaced populations, according to the Joint Strategy Team, the humanitarian coordination body. Travel restrictions have kept most international aid organisations on the outside.

The Joint Strategy Team said some of its member organisations, including KIO health workers, have received limited training from the World Health Organisation in Myanmar. These unofficial sessions, held in government-controlled areas in February and March, covered basic health awareness such as proper hygiene and coronavirus risks. The WHO in Myanmar did not respond to requests for comment.

Asked about UN plans for aid in conflict areas, UNICEF said it is “consistently advocating” for the government to provide “full, safe, and unfettered access”.

“Humanitarian access to reach those in need, whether for the UN, international NGO, or a national NGO, is extremely important,” the agency said in a statement.

Local aid groups are also urging the government to relax its restrictions so that displaced people in rebel-held areas can get healthcare in government-controlled zones. Hospitals in townships held by Myanmar’s government are close to some northern camps, but military checkpoints and tensions with rebel armies make them inaccessible to most.

“We have been in constant discussions with the government’s health ministry to accept the referred patients from [areas controlled by ethnic armies] if displaced people are infected,” said Gum Sha Awng.

He said the health ministry has indicated they will accept patients if needed. But, in practice, it’s the powerful military and their frontline soldiers that control the checkpoints. Officials with Myanmar’s health ministry and its Centre for Disease Control did not respond to interview requests.

Pressure on food supplies

The coronavirus is a top concern in Myanmar’s northern borderlands, but there are also fears that border closures could fuel a larger food crisis regardless of an outbreak.

Zau Raw, who leads a committee overseeing humanitarian aid under the KIO, said food and other relief for displaced people has been decreasing for a while because of a lack of supplies.

With conflict squeezing supply lines within Myanmar, the main source of food in rebel territory since 2016 has been China, said Gum Sha Awng.

“The virus outbreak will impact displaced people along the border directly or indirectly and will lead to a bigger crisis, including food shortages for tens of thousands of people.”

But Chinese authorities in Yunnan have limited the flow of border trade with Myanmar since the outbreak flared in China in January, according to sources in Yunnan, and restrictions have escalated since at least early April as Myanmar’s own caseload began to rise.

“The virus outbreak will impact displaced people along the border directly or indirectly and will lead to a bigger crisis, including food shortages for tens of thousands of people,” Gum Sha Awng said.

Pressure on coronavirus containment in Myanmar comes from multiple fronts. In late March, thousands of jobless migrant workers fled neighbouring Thailand as the country closed its borders and shut businesses like large shops and restaurants.

More than 46,000 people have returned home, including 36,000 from Thailand, according to the health ministry. In a statement, the government warned of possible outbreaks and urged the wider public to self-quarantine and limit their movements.

Many returning workers entered through Karen State in southeast Myanmar, where new clashes between the military and the Karen National Liberation Army have displaced 2,000 since February; at least 6,000 people in the southeastern state have been living in displacement camps since 2017.

“This contagious coronavirus infects very fast,” said Naw Wah Ku Shee, a coordinator with the Thailand-based Karen Peace Support Network. “With the lack of test kits and medical equipment for thousands of Karen civilians, there is a high-risk, life-threatening situation for thousands of people.”

eh/il/ag

Subscribe to our coronavirus newsletter to stay up to date with our coverage.