Questionable practices in the Ebola response in the Democratic Republic of Congo, including payments to security forces, renting vehicles at inflated prices, and job kickback schemes, may have jeopardised humanitarian operations and put lives at risk.

A months-long investigation by The New Humanitarian into the so-called “Ebola business” found such practices, which are also reported in a recent draft operational review commissioned by a group of UN agencies and NGOs looking at corruption and fraud across the wider aid sector in the country.

Together, the reporting TNH began in mid-2019 and the work carried out by the review’s authors from January into April 2020 show how an "Ebola business" evolved around the aid effort in Congo, raising concern for future emergencies, including a new Ebola outbreak in a northwestern region.

The stream of hundreds of millions of dollars in Ebola response funds into a country that Transparency International ranks as among the world’s most corrupt has created fertile ground for conflicts of interest and competition to profit.

Among the issues noted in the draft review, which is based on more than 400 interviews, are alleged sex-for-work schemes and suggestions that those who raise concerns about corrupt practices within the response may put themselves at risk.

Read our related investigation on the aid scam that spurred the review → EXCLUSIVE: Congo aid scam triggers sector-wide alarm

The response has been led by the Congolese Ministry of Health, with technical and operational support from the World Health Organisation. More than a dozen other groups have also been involved in providing support.

Strides made in containing and treating the disease have come in the midst of ongoing militia violence. Community mistrust rooted in decades of conflict and government neglect has also fostered unease among local residents, national authorities, and international interveners.

Attacks on treatment centres and Ebola workers have long plagued the response – 11 response workers have been killed in more than 400 attacks since the beginning of the outbreak in August 2018.

In May 2019, at the WHO’s annual assembly, an oversight body of the WHO established after the West African Ebola epidemic released a statement saying, “the response needs to be reset.” Referring to attacks on health workers and facilities, their report stated: “A growing consensus within the response community is that some attacks are motivated by frustration over so-called ‘Ebola Business’.”

In its investigation, TNH obtained information drawn from leaked WHO documents that suggests how some health workers and civil servants profited from response funds; and how, in the rush to scale up a response in an active conflict zone, the WHO paid millions of dollars in inflated per diems to Congolese security forces.

“Ebola business is not new to this epidemic,” Gary Kobinger, an expert adviser to the WHO who researched these issues during the response, told TNH, adding, but “I’ve never seen as much embezzlement and money inadequately allocated as I’ve seen in this epidemic.”

The authors of the draft review commissioned by the UN and NGOs – obtained exclusively by TNH – warn that “practices implemented during the Ebola response will inevitably have a direct impact on the ability of aid organisations to control corruption within their programmes”.

Groups involved in the response have long acknowledged challenges.

“There are always risks involved in an emergency response of such breadth and complexity,” WHO spokesperson Margaret Harris told TNH in April. “What’s important is having processes in place to deal with problems, and constantly evaluate and improve our processes. We carry out regular audits of all our response operations and act on the findings and recommendations of the auditors.”

“Communication is key to the success for every outbreak and epidemic control,” said John Ditekemena, a Congolese infectious disease specialist.

A unit set up by UNICEF has made more than 100 recommendations based on the latest Ebola response in Ituri and North Kivu outbreak and aims to implement them “across several countries, adapting to new contexts presented by outbreaks such as the current COVID-19 pandemic”.

Some of the problems it found involved excluding traditional healers and communication missteps that mischaracterised symptoms of Ebola, as well as using unfamiliar vocabulary or having inadequate local language support.

“Several studies found that this caused distrust amongst communities,” the unit found.

The Red Cross, meanwhile, has said it has been working to strengthen its operations to guard against fraud and corruption. It lost more than $5 million in aid money during the West Africa outbreak. Auditors found overpriced supplies and non-existent workers.

“In recent years, IFRC has significantly strengthened fraud and corruption prevention, detection, and investigation in line with industry best practice in high-risk operations,” said Euloge Ishimwe, head of communications for the region.

The UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, acknowledged there had been challenges in the Ebola response – Ituri and North Kivu provinces are relatively remote and located inside an active conflict zone. The community is also largely distrustful of the government.

“I’m pretty sure there will be lessons learnt that will be shared by the entire community so that we will be able to look at how we do the things differently,” said Joseph Inganji, the head of OCHA in Congo.

Inganji added that with the new outbreak in Mbandaka, “some of those lessons – or what I’ll call complaints – that were seen in areas in the eastern DRC – have already been rectified because things are being done somehow differently”.

A potential difficulty in addressing alleged corruption within the response, said Kobinger, who participated in the assessment for the WHO’s oversight body, is a lack of mechanisms for Ebola response staff to report issues or complaints. “We saw permanent WHO staff attempt to raise the alarm several times and they were sent back home,” he said.

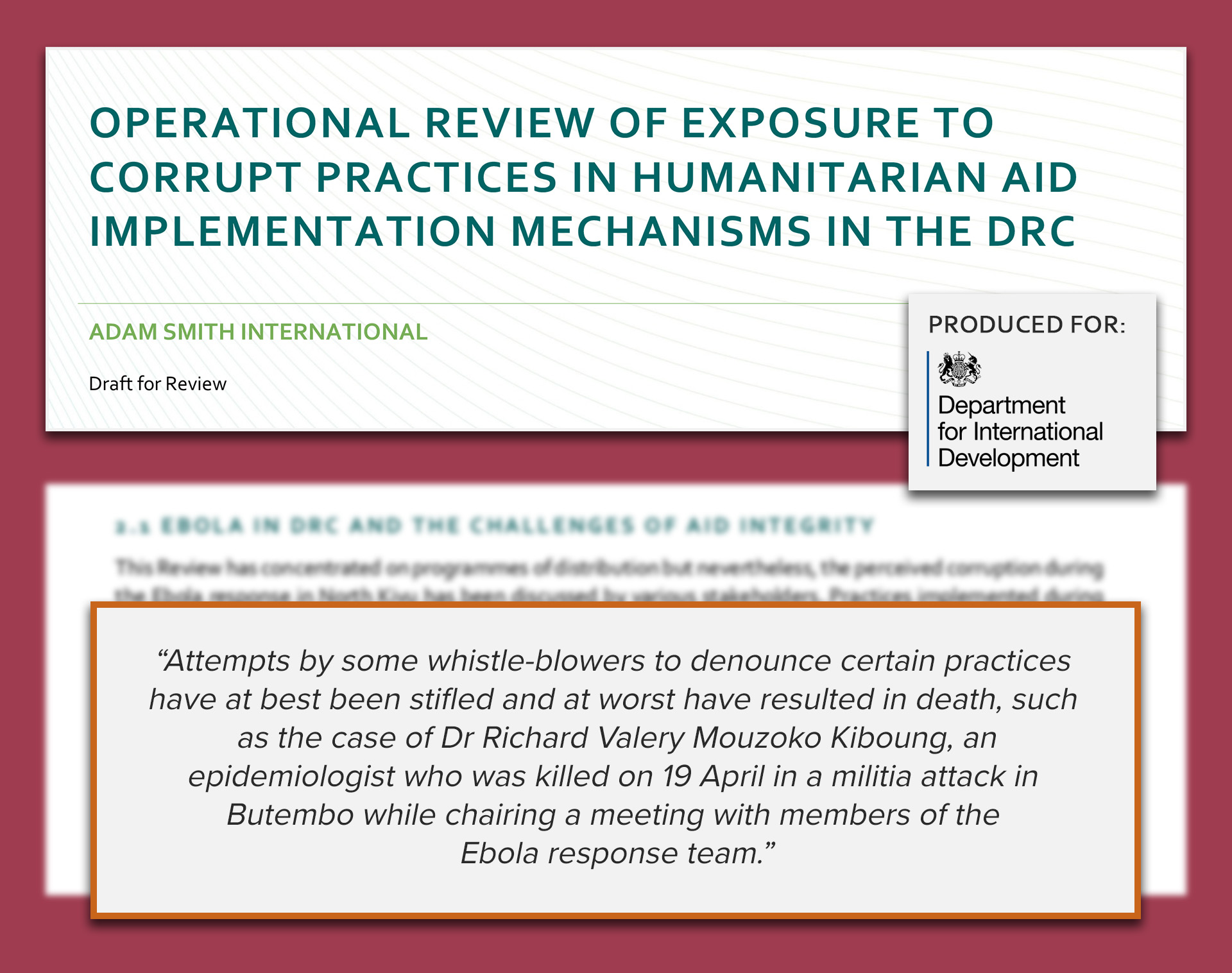

The authors of the UN/NGO draft review charged that, “attempts by some ‘whistle-blowers’ to denounce certain practices have at best been stifled and at worst have resulted in death, such as the case of Dr Richard Valery Mouzoko,” referring to a Cameroonian epidemiologist who was working for the WHO when he was killed in an attack in April 2019.

Four months after Mouzoko’s death, the police arrested several doctors working for the Ministry of Health who allegedly ordered Mouzoko’s murder. They have since been released.

The WHO would not say whether Mouzoko had raised concerns about practices in the Ebola response. “Because the report is a leaked unpublished draft, we are not able to comment on it,” Harris told TNH on Tuesday. “We look forward to the publication of the final report and we will carefully consider the recommendations.”

In January, David Gressly, the UN’s former emergency Ebola response coordinator, told TNH that the attack on the WHO doctor may have been motivated by a desire to divert resources to local health workers.

Chaos, mistrust, and hostility

Congo is home to one of the world’s most complex and long-standing humanitarian crises, and kickback schemes have long existed there. But they proliferated with the influx of Ebola funds, according to dozens of people interviewed by TNH.

“Communities could see with their own eyes – the amount of money people [made] from this response,” said Alex Wade, head of mission for Congo at Médecins Sans Frontières, which managed a budget in 2019 of some $37.6 million of response funds.

“The incentives people were getting paid [created] daily salaries which were completely unheard of in these areas,” he said.

Emails and other material obtained by TNH offer a window into how some of the response funds were managed and show that standard operating procedures were sometimes lacking.

TNH interviewed more than 30 people in 2019 working in the response, and followed up with additional reporting this year, totalling roughly 70 interviews. Many of those people described a chaotic situation that lasted well beyond the early stages of the response.

The Ebola outbreak in Congo’s Ituri and North Kivu provinces, the second deadliest to date, has killed 2,279 people since it was declared, while a new outbreak in the northwestern town of Mbandaka was announced on 1 June and has so far claimed at least 11 lives.

The outbreak that erupted in North Kivu and Ituri was the first in an active conflict zone, and response operations had to be shut down on numerous occasions because of attacks against clinics and health workers, leading to fresh spikes in Ebola cases and deaths.

The WHO “had to be operational right away in an area where there were no known or UN-approved suppliers”, Harris told TNH, describing the beginning of the response in the North Kivu province. “We had to ramp up quickly – find office space, lodgings, supplies, and rent cars to be able to work. Our priority was to save lives.”

Several organisations leading the response said community mistrust hampered operations from the beginning. The oversight report of the WHO specifically noted how community feedback was not used to shape the Ebola response strategy, making it difficult to address community resentment, mistrust, and hostility.

The WHO “had to be operational right away in an area where there were no known or UN-approved suppliers. We had to ramp up quickly – find office space, lodgings, supplies, and rent cars to be able to work. Our priority was to save lives.”

The response was initially led by then-minister of health Oly Ilunga – arrested in September 2019 and later jailed for diverting Ebola response funds, which he disputes – and then by Jean-Jacques Muyembe, who was part of the research team that investigated the first known Ebola outbreak in 1976.

Interviewed by TNH in March, Muyembe said the government had not been managing the bulk of the response funds. Later attempts to reach Muyembe about allegations of mismanagement based on TNH’s reporting went unanswered, as did attempts to reach officials from the Ministry of Health.

The WHO has managed more than $361 million of more than $700 million in Ebola response funds and is requesting $28.5 million to keep the Ebola response going, with additional funds going to the new outbreak in Mbandaka.

Kickbacks and sexual exploitation

The Ebola response has employed thousands of people for a range of services, from burying the dead to disinfecting homes contaminated by the virus. Allocating those jobs to so-called “daily labourers” opened the way for a variety of seemingly corrupt practices, according to TNH reporting and interviews by the authors of the draft review.

Read more → EXCLUSIVE: Leaked review exposes scale of aid corruption and abuse in Congo

The WHO usually did not hire the “daily labourers”, several of those workers told TNH. The labourers usually worked under the Ministry of Health, and the WHO paid an incentive of $10 to $15 per day on top of the government salaries – making the jobs all the more desirable.

Such “top-ups” are not uncommon. However, in some cases the jobs came at a price.

“If you want a job, you need to do an opération retour [‘project return’, a kickback] to the person who hired you,” one worker told TNH, noting that this practice often occurs elsewhere, both inside and outside the aid world. “Everything here is opération retour! That’s how things already worked before Ebola.”

Another Congolese daily worker, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of losing his job, told TNH a similar story in September 2019. “A nurse called me to say that he had a job for me,” he said. “When I arrived at his office, he told me that to get a job, I’d need to give him back at least 30 percent of my salary each month.”

The “price” of such jobs may include sex, according to allegations by individuals interviewed for the draft review, further contributing to the sexual abuse and exploitation of women.

“Sexual exploitation, especially sex for work, has been reported by interviewees,” the authors of the draft review wrote. They referenced a report that found that “many indications that men in decision-making roles [for the Ebola response] have used their position of power to subject women to sexual abuse as an employment pre-requisite or prior to receiving their salary”.

The WHO declined to say whether the world health body had received any reports of sexual exploitation within the Ebola response.

In addition, some people appeared to be getting paid multiple times for doing different full-time response jobs simultaneously.

Information drawn from WHO documents that tallied the number of workers paid by the world health body appeared to show that at least 60 people were listed for multiple full-time jobs as of August 2019. The information was shared with TNH by a person who was concerned about improprieties in hiring and payments, and who requested anonymity for fear of damaging professional relationships.

When asked about these allegations, Harris told TNH that the WHO could not confirm the veracity of the information or the accuracy of the figures without seeing the material TNH obtained.

The WHO also said it worked with global accounting firm Deloitte to reconcile the database against the beneficiary payment list and identify any irregularities. At the beginning of June, the world health body noted that this work on a biometric database to centralise the validation and tracking of all payments to Ebola workers was “progressing”.

Soldiers of fortune

To counter the risk of violence against health workers, the Ebola response has relied on security forces for protection.

When providing security forces with training or funds, the UN has a policy to ensure that its support will not inadvertently contribute to human rights violations, and UN agencies have to do due diligence on the security forces they provide support to.

According to the policy, prior to paying millions of dollars to security forces from the beginning of 2019 until March 2020, the WHO should have asked the UN Joint Human Rights Office to conduct this due diligence for them.

The WHO initially told TNH by email that it had done “checks against the UN human rights database on all national security personnel”. Later, however, in a 15 May email, Harris explained that when the response was launched in August 2018, it didn’t do the full due diligence as the “WHO faced urgent, life-threatening situations as it went about its public health work and did not receive adequate support and protection from partners with expertise and a mandate to provide security in high-risk settings.”

Humanitarian NGOs such as the Red Cross and MSF have criticised the militarisation of the response, arguing that negotiating access with armed groups and earning community trust would result in a safer situation, as paying security forces creates an incentive to stir insecurity.

According to the Kivu Security Tracker, a project that monitors violence in the region, the police and the army have killed about 50 civilians in Beni and Butembo – the two main cities near the epicentre of the outbreak – since the beginning of the response.

Some who were shot by the Ebola response’s own escorts last year described their experiences to TNH. In another case, one not related to the Ebola response, a police officer attempted to rape a woman and then killed her.

According to an internal WHO document shared with TNH by a source on condition of anonymity, the organisation paid 1,386 members of the Congolese security forces a total of $598,800 for a single month in June 2019. The WHO told TNH in an April email that payments covered daily stipends for food, car rentals, and fuel.

The monthly per diems amounted to roughly $300 per person. Annual per capita income in Congo is about $560, and the standard UN per diem rate for police officers is between $3 and $4 per day, according to Gressly. The WHO was paying more than double that – a rate, Harris told TNH in April, that was set by the Congolese government.

The draft review – a final version of which is expected to be made public next month – also noted the payments to the Congolese security forces, and said people who were interviewed for the review reported being pressured by “armed movements to use paid escorts and that refusal can lead to security incidents”.

The WHO told TNH in an April email that payments to security forces have now stopped, but also maintains that security escorts have been vital to protect responders.

The WHO declined to say how much money had been spent on Congolese security forces, saying it “cannot disclose security related information” during an ongoing response.

The group’s report to donors, covering August 2018 to June 2019, states that $5.4 million was spent on security, but offers no breakdown of how money has been allocated.

Driving a culture of corruption

While reporting from the outbreak zone in mid-2019, TNH also found irregularities in vehicle rental practices during a window of the response.

“The amount of cars they were driving is an advertisement of the money there was,” said MSF’s Wade.

The WHO’s fleet of some 700 rented vehicles cost between $1.3 million and $1.9 million a month from March to September 2019, Harris, the WHO spokesperson, told TNH via email.

According to WHO documents TNH obtained, a dozen civil servants in Butembo rented their private cars to the world health body at rates ranging from $1,800 to $3,000 per month.

Half of those car owners worked for the response, according to internal WHO documents shared with TNH that were then cross-checked with people familiar with the names of civil servants and who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“You don’t need a degree in finance to realise that [it’s bad] to rent a vehicle from someone who works in the response, and that this vehicle is purchased by this person just to rent it,” said Kobinger, the WHO adviser and Ebola researcher. “When other people see this, it creates distrust.”

The WHO conducted its own review in June 2019 – nearly a year after the response began – and found “a mismatch between the volume of leased vehicles at high overall cost and the volume of work”. It also found an “absence of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for logistics that [should] govern all response emergencies and new outbreaks”.

The draft operational review noted that practices criticised in the West Africa Ebola response in 2014-2016 included paying high rental fees to car owners, and the use of allowances and other incentives that limited the response and endangered staff.

“You don’t need a degree in finance to realise that [it’s bad] to rent a vehicle from someone who works in the response, and that this vehicle is purchased by this person just to rent it. When other people see this, it creates distrust.”

Some of those same problems carried over into the recent response, the draft review stated, noting high expenditures spent on vehicles “in which price negotiation has been virtually absent with the excuse of the need for fast operationality”.

According to internal WHO documents leaked to TNH, Dr Jean-Christophe Shako, who had been an Ebola response coordinator for the Ministry of Health and is now a COVID-19 response coordinator in Kinshasa, rented his personal vehicle to the WHO from December 2018 to March 2019.

By the time his rental contract ended, Shako had earned nearly $10,000, according to the documents seen by TNH. When contacted by TNH, he denied renting his car to the Ebola response.

The WHO said the “irregularity” of renting Shako’s car took place when a rapid scale-up of activities was occurring, and that the “need to rapidly find and directly rent vehicles made an instance like the Dr Shako example potentially more likely”.

While Shako was renting his own car out to the WHO, the WHO was providing him with work cars, according to documents seen by TNH. One of those cars was allegedly owned by another prominent figure of the Ebola response: Blaise Amaghito, the head of the national intelligence agency in Butembo and the head of the security committee in that town – a position for which he earned $750 per month, paid by the WHO, according to internal WHO documents leaked to TNH by two separate WHO employees.

According to the documents, Amaghito earned about $100,000 for the rental of seven cars between December 2018 and June 2019. When contacted by TNH, Amaghito denied having rented vehicles to the response.

The WHO did not comment on the allegations around Amaghito or on other cars rented to response workers or civil servants found in the documents TNH obtained, saying an internal investigation had been opened after allegations made in media reports.

The world health body told TNH that by February 2019 all car rental contracts had been moved to local rental car agencies, and that strict procedures were put in place. However, documents obtained by TNH showed that Amaghito had rented vehicles to WHO up until July 2019.

Lessons learned

After 22 months, the Ebola response continues. Many had hoped an end was near for the outbreak in the Ituri and North Kivu provinces until a resurgence of cases appeared in April.

Although there have been no new cases since 27 April, it won’t be until the end of June when officials will be able to officially declare the outbreak over, and the WHO wants $28.5 million to keep the Ebola response going, with additional funds going to the new Mbandaka outbreak.

Noting achievements made during the nearly two-year response, the WHO pointed to lives that were saved because of vaccines, treatments that dramatically lowered death rates, and prevention measures that helped to contain a regional spread.

The WHO said it was incorporating lessons learned from earlier phases of the response into current operations, and also continuing to identify risk mitigation strategies and decentralising operations, which may mean “making the case to donors that there is a need to provide more funding for what is seen as staffing costs”.

Jeremy Konyndyk, a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development who led an oversight mission last year looking at WHO’s management of the epidemic, said part of the problem going into the response was a lack of capacity.

“The donors – and certainly the World Bank – should probably have done more due diligence at the outset to compare WHO’s in-country financial management capacity to the contextual risks and the volumes of money they were putting in.”

“WHO did not initially have the field-level administrative capability to sufficiently manage that volume of money in that kind of challenging environment,” Konyndyk said.

“The donors – and certainly the World Bank – should probably have done more due diligence at the outset to compare WHO’s in-country financial management capacity to the contextual risks and the volumes of money they were putting in.”

Harris noted that financial management capacity has already increased for the team dealing with the COVID-19 response – for which the WHO is requesting $1.7 billion.

In the draft review, UN agencies were singled out for a litany of problematic practices in aid operations across Congo, but a separate section on the Ebola response warned that some practices “represent serious risks to the integrity – not only for the Ebola response – but for all humanitarian responses in North Kivu”.

But Konyndyk was hopeful for the WHO's capacity to learn from any mistakes in the Ebola response. “I think they recognise the problem and are making adjustments,” he said. “This is largely the growing pains of building out an ability to work at scale in really tough places.”

Additional reporting for this story was contributed by a reporter whose name is being withheld due to security reasons.

(This project has been funded by the European Journalism Centre (EJC) via its Global Health Journalism Grant Programme for France. While some material in this story is exclusive to TNH, other material contained was previously published in French by Libération.)

ef/pd/ag