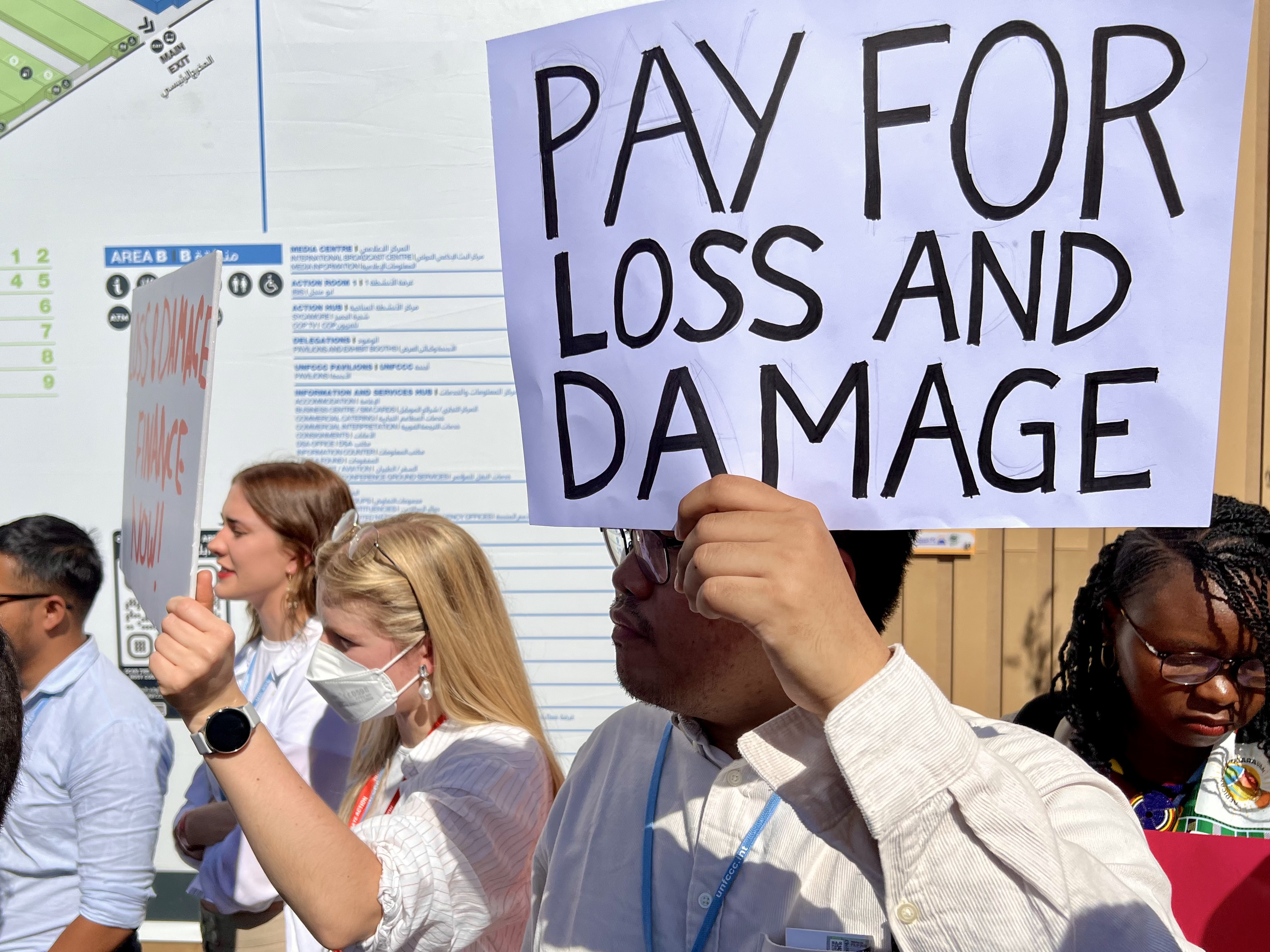

Financing for loss and damages is firmly on the agenda after years of wrangling and pushback. But the end result is far from certain as the COP27 climate summit pushes through its final week.

Communities on the front lines of the climate emergency are hopeful these negotiations are the first steps toward financially addressing the destruction they’re experiencing in a crisis driven largely by outsized historic emissions from wealthier nations.

But following an oft-run script, the largest so-called developed countries are still pushing back against the idea of funding loss and damages, instead promoting their contributions to other less-divisive areas of climate finance.

During a pitstop visit at the seaside city hosting this year’s summit, Sharm el-Sheikh, US President Joe Biden announced some $250 million in new or increased funding focused on helping countries adapt to or prepare for climate threats. Germany also launched a protection scheme supported by G7 countries, called the Global Shield, that would provide access to insurance ahead of extreme events.

“We are seeing more frequent extreme weather events that are impacting people at a larger scale than any of us thought was likely. Humanitarian response is not good enough for that.”

While climate activists and vulnerable countries see loss and damage funding as a matter of reparations and climate justice, wealthy nations have resisted calls for compensation and liability, afraid that costs could spiral.

To sift through some of the key issues around loss and damage, The New Humanitarian spoke to a range of voices attending COP27: people from disaster-hit communities, frontline humanitarians, aid workers, and officials from governments pushing for change.

Humanitarian emergencies fuelled in part by climate extremes – such as months-long floods in Pakistan, and unprecedented drought and famine-like conditions in Somalia and elsewhere in Horn of Africa – have laid bare the reality of loss and damage for people on the ground, and for world leaders and negotiators at COP27.

“Climate change has taken everything from us,” said Koyam Boulama Falmata, a displaced herder from a drought-hit part of Niger who travelled to COP to present her community’s case. “It took our crops, it took our herds, our homes, and it took our children. There is no water to drink, there is no food, there are no doctors.”

The New Humanitarian: What does loss and damage look like on the ground?

María Gracia Aguilar, Peru representative for Fundación Avina, an organisation that channels assistance from governments, international agencies, and NGOs to help communities adapt to climate change: Loss and damage happens when we can no longer adapt. Glacier retreat in the Andes will mean that we will no longer have any water if we don’t adapt. Therefore, people who rely on farming will be missing a basic necessity that is water, to live with. If you don’t have that, you have to migrate, change your economic activities, and so forth.

Emtithal Mahmoud, a goodwill ambassador for the UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR) and former refugee who was deeply affected by the climate crisis, before escaping from Darfur in western Sudan: For me and my family, it has been a cycle of loss and damage over generations and centuries. It is very difficult to be here in Egypt and speak truth to power, knowing it will take time for power to act. During the time that it takes for power to act, I lose people, and that is unacceptable. There needs to be no lag. Action is something that I would like to see immediately.

David Nicholson, chief climate officer, Mercy Corps: We are seeing more frequent extreme weather events that are impacting people at a larger scale than any of us thought was likely. Humanitarian response is not good enough for that. Resilience is not doing the job. We are seeing a need for new funding, in places where there are fundamental shifts in livelihoods and lives are impacted, in whole areas where you have to reconsider how life is constructed. None of our current programmes can solve that problem.

The New Humanitarian: What should loss and damage finance look like?

Farah Kabir, country director, ActionAid Bangladesh: Loss and damage finance has to be a new strand with funds to support communities and the most vulnerable suffering because of the erratic weather patterns due to climate change. This is not about adding a few pounds and dollars to the adaptation fund; it is not about funding mitigation. It has to be separate. It has been 30 years since this conversation started, and for 30 years, a lot more communities have been affected; a lot more children, women, and girls have been affected. And when you talk about being impacted, it is of a serious nature.

Francine Baron, former foreign minister of Dominica and CEO of the Climate Resilience Execution Agency for Dominica (CREAD), a government agency that works with public and private sectors, as well as civil society to manage disasters and recover from them: It is about the measures we put in place to become more resilient because we will be facing more extreme weather events. Every year we go through the hurricane cycle. As I speak, we had two days of very unusual rain and roads to communities were cut off due to landslides, so we had to bring in food and other supplies for the villagers. We expect that this sort of event will be repeated and become worse as the climate gets warmer. We are therefore really looking at the cost to us to make our communities more safe, more resilient, less likely to suffer the significant impact.

“It also means addressing the centuries of structural violence. If people had the choice socio-economically, they wouldn’t be living in zones of danger. That is what true loss and damage finance looks like to me.”

Emtithal Mahmoud: Loss and damage is investment that is equitable, not after the fact, but investment in adaptation and preparation. There are different approaches to ending climate change, you can clean up damages after everything is lost, or you can try to prepare and strengthen communities against the inevitable. Strengthening and preparing communities doesn’t only mean preparing them right where they are, but it also means addressing the centuries of structural violence. If people had the choice socio-economically, they wouldn’t be living in zones of danger. That is what true loss and damage finance looks like to me.

María Grácia Aguilar: People first need to understand and identify the type of loss and damage that exist, because there is still a lot of information that we do not have. There are not only economic, but also non-economic losses. It’s important, because those are more difficult to quantify, and to put a price on. When you lose biodiversity, it is very difficult to put a dollar amount to it. First you need to identify the loss, and talk to local communities who are suffering, and not just decide from a top-down perspective how much they have lost, to understand what it means for them. After that we can talk about how we repair that, how we need to give back to that.

David Nicholson: The more we commit to adaptation and resilience, the less we will need loss and damage in the long run. But even if we spend all the money in the world for adaptation and resilience in the world, there will still be a subset of events that will go beyond those. We are dealing with a lot of places in the world where the adaptive capacity is just so low. This is on the frontlines of climate crises, in other words places that are most dependent on short term weather changes for their livelihoods, or have the weakest systems of governance, where even the ability to adapt to small changes is limited. And now we are seeing larger and larger changes. When we talk about loss and damage it is really about that gap.

When these events occur, who pays for that? And the who is a very controversial part of COP. I would love to think that this COP was going to solve this result as to where this money is going to come from. But that is not realistic. But we are seeing a commitment to working that out. We all get frustrated with the heavy process of these things, but it’s a reality. What we are hoping to see is a mechanism in place that governments and communities – whatever the mechanism – are able to quickly access money. It’s not the same as humanitarian money. It’s long-term money.

The New Humanitarian: How should a mechanism for loss and damage financing work?

María Grácia Aguilar: It should work with the input and the direction of the communities, and find fast and simple ways to get finance on the ground. We still have the issue where finance remains at the national level and it’s not getting to the impacted communities. In our Andes Resilientes project it would mean ensuring that the communities can access finance, by providing funds that can be accessed directly by the communities from subnational governments in a way that is simple and not bureaucratic.

Farah Kabir: It should be meant to support those who are suffering. We can find the mechanism. We are spending too much time discussing the mechanism and the architecture and governance of it. Tell me about countries, such as the UK and the US where we see scandals, scams, and frauds. Why is it a given premise that when you give money to communities and small organisations, that it is going to be abused or misappropriated? That’s the first premise to be removed. It should be based on trust. You should then find in every country or region mechanisms that already exist through which communities are already receiving funding, and you try to boost that up. If it is about accountability, put the communities in charge of accountability and transparency. They will hold their elected representatives accountable.

“We still have the issue where finance remains at the national level and it’s not getting to the impacted communities.”

David Nicholson: We can learn lessons from the Green Climate Fund, where money has not been getting to communities at anywhere near the pace it should. There is not enough transparency in that system. The loss and damage mechanism needs to be transparent in a way that the subnational governments, communities, and their partners need to access that money in a way that doesn’t require huge resources. And it doesn’t need to have the extent of measurement requirements that get loaded on like with the Green Climate Fund.

Francine Baron: We need to secure our communities and ensure that our people do not become climate refugees. Financing has to be available to individuals who are unable to make necessary changes to their livelihoods to their life situation so they are not impacted in the same way as they were impacted by the last storm. During Hurricane Maria [in 2017], some people who lost everything were able to go to other countries where their families worked to live. But others did not have that option… These are situations where events make people descend into abject poverty. If you do not have the funding, it could be difficult for governments because we constantly have to keep putting money into building back roads and bridges. Most of the time you are still paying a loan for the first bridge, and you now have to find funds for a new bridge. There is an increased cost in making sure that the infrastructure you build can stand up in the next storm. That is where the challenge is for us.

The New Humanitarian: Is loss and damage misunderstood?

María Grácia Aguilar I think that the main misunderstanding is that loss and damage is just an economic loss, thinking that people will have lost their income and pay into that. There are lots of misconceptions regarding non-economic losses, because people are effectively losing part of their identity and culture, and of the way they decide to live. It’s difficult to put a price on that.

Farah Kabir: Negotiators are not willing to understand. When you talk about loss and damage, those who have caused it have to take responsibility. But some countries are not willing to take responsibility. If they were, they would have changed their development or their growth patterns, which they didn’t.

“The words loss and damage within the community means something that cannot be helped. It is similar to the word disaster or crisis. It does not shape these things as problems that have solutions. I do believe these problems have solutions.”

Francine Baron: Ultimately, we are being asked to spend money … to be able to protect ourselves against actions taken by others that are impacting the climate and our lives. In some instances, funding is necessary to repair actual loss and damage, and in other instances, funding is necessary to ensure that you do not have that impact from an extreme event.

Emtithal Mahmoud: When people hear the term loss and damage, the first thing that they hear is the word loss, that something is lost. In terms of language, something that is lost is hopeless and cannot be fixed. Something that is damaged also cannot be fixed. The words loss and damage within the community means something that cannot be helped. It is similar to the word disaster or crisis. It does not shape these things as problems that have solutions. I do believe these problems have solutions.

The New Humanitarian: What should discussions on loss and damage mean for the humanitarian sector?

María Grácia Aguilar: The humanitarian sector has to be integrated into the climate change sector and vice versa. Climate change is such a transversal, cross-cutting issue that will impact all humanitarian issues. If we are not including climate change, whatever project you have will eventually have issues due to climate change. Also, when we talk about loss and damage, we need to integrate humanitarian considerations and development issues, because they are not separate issues in day-to-day life of communities. It is all part of the same thing.

“The humanitarian sector itself has to evolve in the face of climate change.”

David Nicholson: There is no question that the humanitarian sector itself has to evolve in the face of climate change. Shocks are a little more predictable, there could be more preparedness, there can be a little more ability to react to climate shocks. That doesn’t replace loss and damage but the initial humanitarian response could be sharper and can be more targeted and quicker, and it needs to relate to the loss and damage mechanism that comes in. They are fundamentally solving different problems, and we cannot rely on the humanitarian system to solve all those other problems.

Francine Baron: If we are successful in mobilising the resources necessary for countries to address the challenges, you will have less impact on individuals and communities, and therefore you can avert a humanitarian crisis. It may require an outlay of capital now, but it will have benefits later on.

Edited by Irwin Loy.