Displaced by drought and conflict, rural Somalis have been heading to Mogadishu in their tens of thousands. They get no safety or support and are increasingly targeted for forced evictions, but they are still coming.

After yet another bad rainy season at the end of last year, Amina Muse abandoned her four-hectare farm in Qorylooley, a small village in southern Somalia.

For Muse, no harvest meant no business, and no business meant she would struggle to buy food or other essentials until the next rainy season in three months’ time – if those rains came at all.

Uncertain what to do, Muse called friend and former neighbour Faduma, who had left Qorylooley in 2013 when fighting erupted nearby between al-Qaeda-linked al-Shabab militants and government forces.

Faduma made her way to the capital, Mogadishu, finding refuge in a settlement for displaced people in the heart of the city. Muse asked her how life was now. Faduma told her she was barely surviving, reliant on the goodwill of neighbours and occasional odd jobs, washing clothes and selling any goods she could find.

Muse considered those bleak prospects then looked at her land. “I didn’t think I had a choice,” she told IRIN. “My only option was to move to Mogadishu.”

“The leveller”

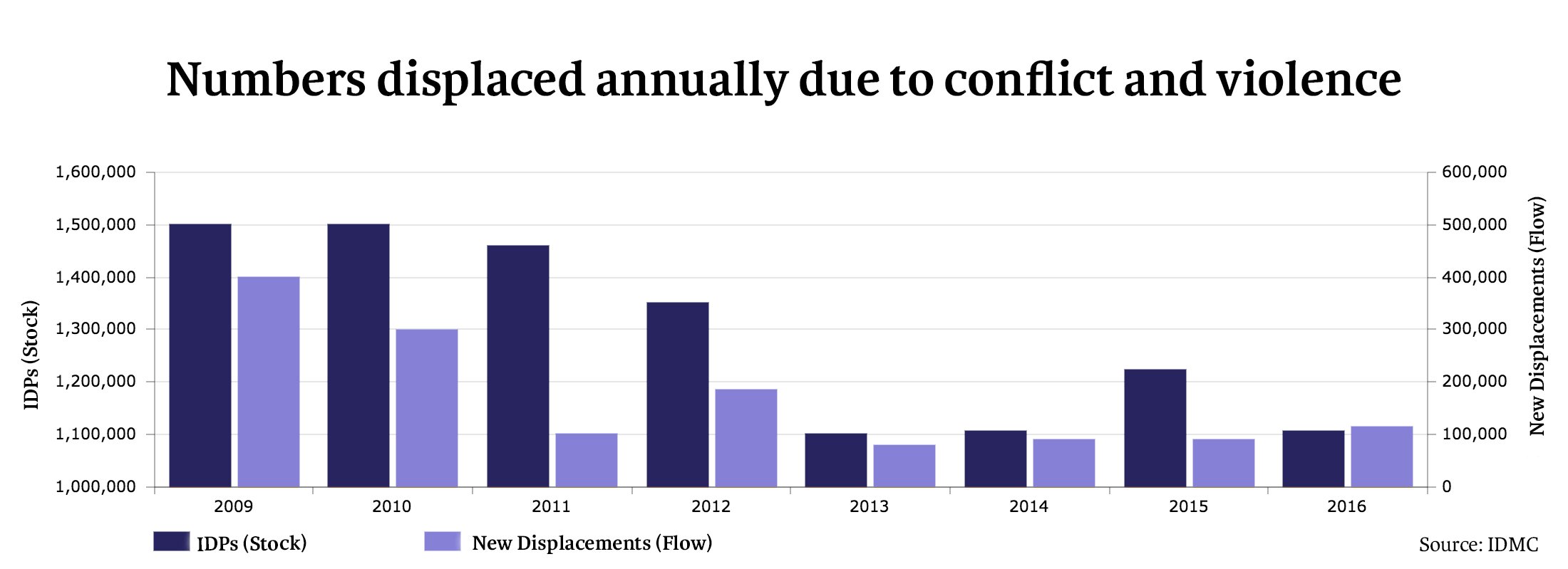

The decade-old conflict between al-Shabab and the government has driven hundreds of thousands of Somalis from their homes.

But even as the scale of violence-related displacement has dipped in recent years, the impact of food shortages as a result of climate-related shocks – from drought to floods – means the level of disaster-affected displacement has risen steeply over the same period.

One million Somalis were displaced by drought and conflict last year, according to OCHA, the UN office that coordinates humanitarian aid.

The rains in Somalia have underperformed for four successive seasons and today everyone – from farmers in the previously fertile south to pastoralists herding camel further north – has felt the impact.

Smallholder farmers are producing smaller harvests; water points have become scarce; and large numbers of livestock have died in a drought Somalis now refer to as “the leveller” due to its far-reaching effects.

Their livelihoods withering away in front of them, many rural Somalis have few options but to migrate to the large towns in the hope of finding new sources of income.

In a recent technical study, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization noted that 2.7 million Somalis are still in urgent need of emergency assistance.

It could have been far worse. Somalia was one of four countries where famine was feared in 2017. Aid was dramatically scaled up and, as a result, food security has markedly improved, according to the FAO report.

But Mogadishu has seen a surge in internally displaced people (IDPs) escaping the drought and violence in the countryside who now squat in makeshift camps on increasingly valuable private land. The response from the authorities has been to clear them.

Growing friction

On the 29th and the 30th of December last year, 21 IDP settlements were destroyed on the outskirts of Mogadishu. Witnesses described bulldozers and vehicles arriving early on the morning of the 29th, demolishing homes and schools, and forcing more than 5,000 families to flee for settlements further from the city.

“The evictions were done with no prior consultations, and numerous requests by the community for time to collect their belongings and to safely vacate were not granted,” noted the Somali NGO Consortium.

Many of those displaced were forced to move into areas where al-Shabab maintains a presence, making access by aid organisations more difficult.

According to the Norwegian Refugee Council’s “eviction tracker”, some 11,000 IDPs are evicted on a monthly basis in Mogadishu, with a total of 153,682 people made homeless in 2017.

Land values have increased significantly as both relative stability and business opportunity return to Mogadishu. Displaced people – some squatting in what were once abandoned districts but are now some of the most desirable real estate and commercial locations – find themselves extremely vulnerable.

“Land is a contentious issue here and always has been,” Justin Brady, the head of OCHA in Somalia, told IRIN. “The idea that we will get prime land in the middle of the city that internally displaced people can live on is unrealistic, and the fact that they are getting pushed further and further outside the city is concerning.”

The war’s environmental impact

The “prime land” Brady describes is exactly where Muse now lives. Overlooking the rusted tin roofs, dust-laden tarps, and dilapidated shanty homes is the exclusive neighbourhood known as Villa Somalia, where the president and other influential members of the government reside.

Decades ago, those buildings were also home to some of the greatest environmental protection efforts in East Africa.

From 1961 to the outbreak of civil war in 1991, the one-party government of dictator Siad Barre established the National Range Agency and expanded the Ministry of Agriculture, which developed policies to protect pastures from overgrazing, banned charcoal exports to preserve forests, and established a national environmental day (celebrated not once, but three times a year).

With the outbreak of civil war and the collapse of the federal government in 1991, these programmes disintegrated.

This decline of good environmental governance, combined with the changing climate over the years, has placed pastoralism and farming – the economic and social backbone of the country – under threat. Lush grassland has become desert; increasingly unpredictable rainfall has led to more frequent and severe droughts.

Climate change means more failing farms and more displacement as people like Muse are forced from their homes.

“The Horn of Africa, Somalia in particular, is seeing the impacts of climate change, though it had no hand in contributing to global carbon emissions that are the cause of it,” said Brady. “It’s putting not just livelihoods but an identity of a people at risk.”

Aid versus development

The risks of getting it wrong in Somalia are well known. When an extreme drought struck the Horn of Africa region in 2011, Somali was worst hit. Between 2010 and 2012, the country suffered a famine and nearly 260,000 Somalis died, half of them children under five. An earlier 1994 famine in Somalia claimed an estimated 220,000 lives.

Since the end of the 2011 drought, the UN has spent an estimated $4.5 billion on emergency relief efforts to avert another famine in Somalia. In January this year, the UN appealed for another $1.6 billion for drought relief efforts in 2018.

The severity of the recent droughts has meant the vast majority of donor funding has been funnelled into emergency relief rather than long-term development of water resources, environmental preservation, or diversifying livelihoods beyond traditional farming and livestock herding.

As a result, though acute crises have been mitigated, the future of Somalis whose livelihoods are increasingly under threat remains uncertain.

Experts say that responding to climate change means developing adaptation strategies – longer-term measures that help communities cope with the impact of a drying environment, rather than short-term humanitarian relief.

“In the long run it’s very clear that we need to move in a different direction in terms of livestock management and agriculture,” Peter de Clercq, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator in Somalia, told IRIN. “It’s time for us to think strategically if we want to break the cycle of humanitarian crisis, at least the part of that we can influence.”

cg/oa/ag

TOP PHOTO: A young Somali girl walks through an IDP camp near the town of Beletweyne