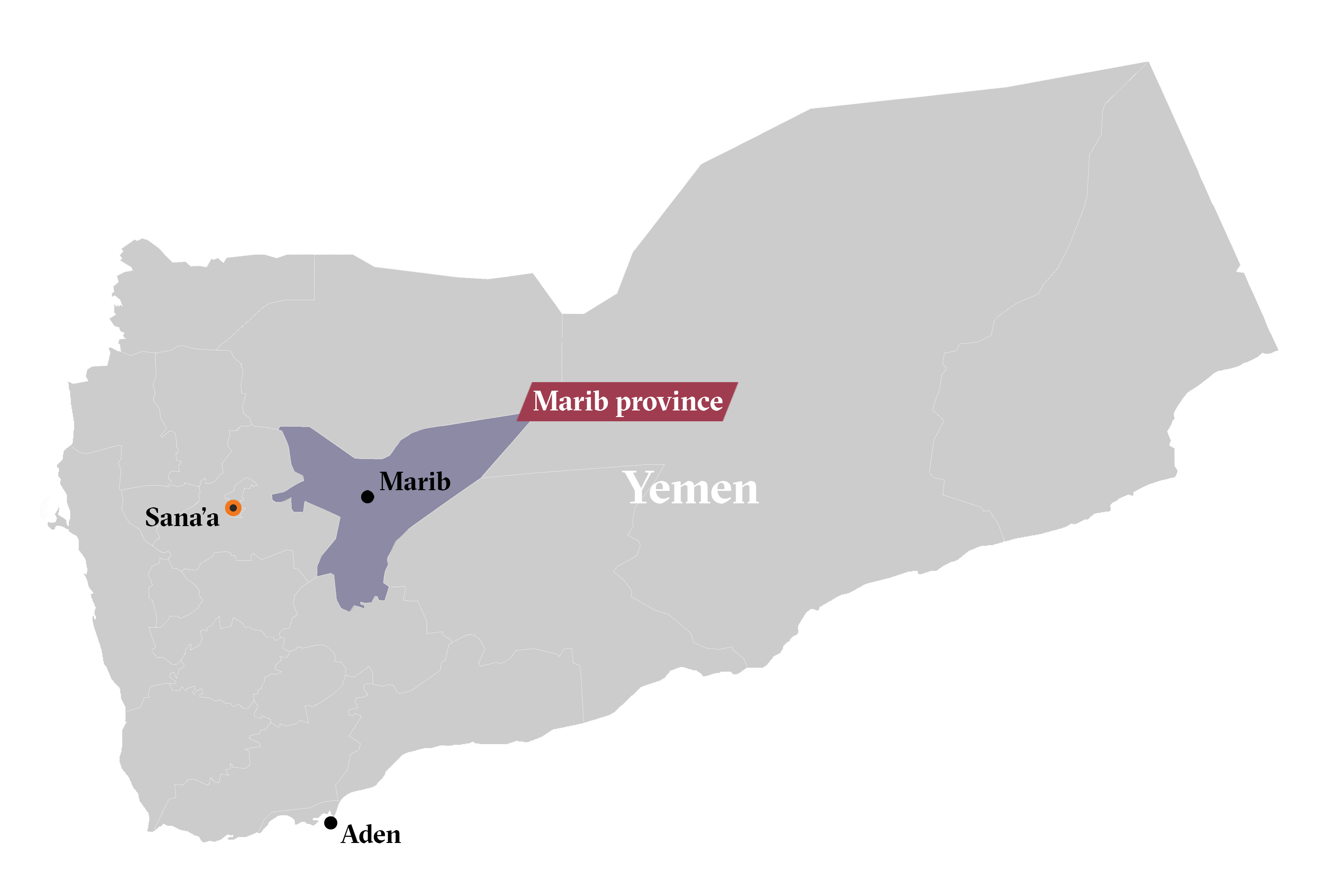

When I visited Marib three and a half years ago, it was being sold as an island of stability and prosperity in the middle of Yemen’s violent war. I didn’t quite buy that line, but I also didn’t foresee the danger and dread that are bearing down on the central province and city now.

In the past few months, thousands of people have been forced to run from bombs and bullets as a Houthi rebel offensive closes in on the area. The reports of fighters dying in brutal battles and missiles ripping through residential neighbourhoods and camps where displaced people are sheltering could not be further from the image I and other journalists were presented with in late 2017.

The difference is stark, but perhaps in countries as bitterly divided and decimated as Yemen has become, such a drastic change shouldn’t come as a shock. As many Yemenis have learned over the past six years of war, even the things everyone should be able to take for granted – safety, home, regular meals – often don’t last.

Read more → Peeking through the cracks into Yemen’s war

Before war broke out in March 2015, Marib was seen as something of a sleepy backwater, albeit one with a proud and rich history that includes the Queen of Sheba (Bilquis in Arabic). Over the first year or so of the conflict, it then became a fiercely contested front line in a battle between Houthi rebels (then allied with former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who has since been killed) and an internationally recognised government, backed by a now increasingly frayed Saudi Arabia- and United Arab Emirates-led coalition.

But by the time I arrived, the area was firmly in the hands of the coalition and the Yemeni army, which boasted a large base in the city. Business was booming, construction was everywhere – there was even talk of a new airport and a state of the art football stadium (the first never materialised, the latter did).

While most Yemenis were living amidst a cholera epidemic, clean water here was flowing into homes from a dam that only a few years earlier was being fought over.

Hundreds of thousands of people – maybe even millions – came to live in Marib, escaping war or persecution elsewhere in the country, and the area became a safe haven of sorts for those opposed to Houthi rule. Before 2015, it was home to around 400,000-500,000 people. Now, numbers are upwards of two million, depending who you ask. Many touted the province, and the leadership of its governor, Sultan al-Arada, as a possible way forward for Yemen.

‘The next days will be very hard’

At the newly built university in 2017, I met a student named Mahmoud, whose surname I’m withholding for his security. He was studying English and was particularly excited about the plays of George Bernard Shaw.

We’ve kept in touch on and off over the years, as he graduated and took a job teaching private English lessons. He’s 26 now, and has around 40 students. He loves his job.

Since February, when the assault gained steam, I’ve been wondering and worrying about Mahmoud and the other people I met in Marib. Humanitarians have warned that the violence could force another 385,000 people to flee their homes, and the knock-on effects could push an already starving country even nearer to famine. More than 13,600 people have already taken flight this year.

The governor’s home, where I sat with other journalists, has been shelled. A powerful military commander, a man who sat next to him in stone-faced silence, has been killed, and the UN’s refugee agency said there were 40 civilian deaths and injuries in Marib in March alone.

When Mahmoud and I spoke earlier this month, I found him fairly sanguine about the fact that the front line is only around 20 kilometres from the city, and that he can hear rockets regularly. He described his current emotional state as “acceptance”, of the fact that “the next days will be very hard”.

Perhaps I should have been more surprised by his calmness, but one thing I’ve learned in years of reporting on Yemen is that people can adjust to horrible things.

As the economy has gone into a full-on meltdown, Yemenis have sold off their jewellery and their furniture. They have become accustomed to cutting their shopping lists and choosing who will or won’t eat at a particular meal. It has become normal to join up with various sides in the war, sometimes because of deep belief in a cause, and sometimes for the money (although there isn’t much money to be had for regular fighters these days).

Yemenis have spent long years separated from family and friends, and become used to more funerals than anyone should have to attend. COVID-19 crashed into Yemen last Ramadan, the Muslim holy month, and as the holiday gets underway this year, there’s a second wave.

For Mahmoud’s part, he said death has just become a part of his day-to-day life. His best friend, Ali, was killed in 2016; he had driven over an explosive while serving in the army. “Every day, you turn on your mobile and you read the news that one person’s friend is dead, another is dead,” he told me.

Mahmoud now rushes his crying young nieces and nephews to a safe room in his family home when they hear rockets. I asked him what type of safe room he has. He said there isn’t really anywhere safe, so they just go to the eastern part of the house – the rockets come from the north and the west.

Act on the warning signs

In 2017, I wrote about how – while leaders were keen to discuss their confident posture for the future – you could still see signs of Yemen’s humanitarian catastrophe in a place like Marib. Displaced people were sleeping in an unfinished community college; the hospital was pockmarked by bullets, full of wounded soldiers, and short on supplies; and the military vehicles wheeling around the city centre did not exactly say “peace”.

That’s not to say I predicted any of this, or that I had some particular insight into how long the war would go on, or into how much worse almost every aspect of life would become for ordinary Yemenis. It would be another year until the first real warnings of famine, and even though one has still not been declared, there is no question that millions of people in the country are going hungry.

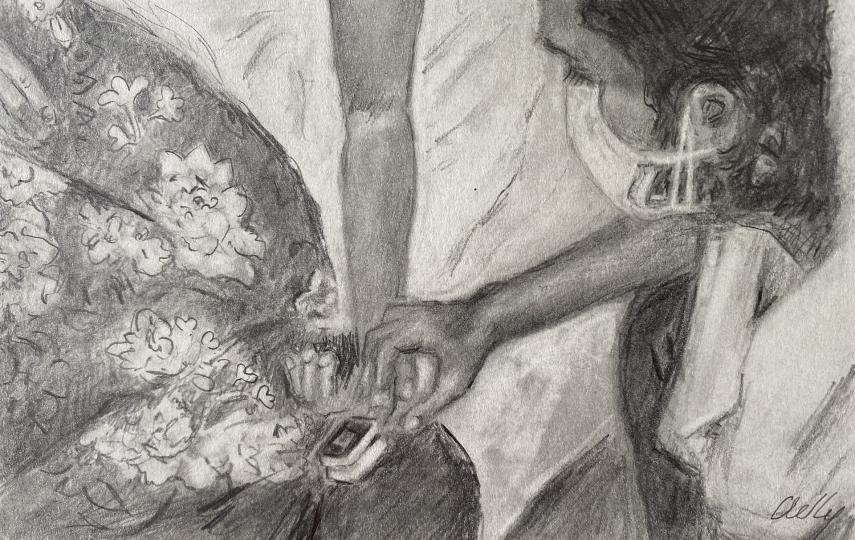

A soldier (pictured in blue jacket) watched over Marib from the top of a hospital in 2017, when the city and province was in the midst of a construction boom and hopes for long-term stability were high (Annie Slemrod/TNH). In the last few months, thousands of people have been forced to flee an offensive in the area, sheltering in camps like this one in October 2020 (Ali Owidha/REUTERS).

Journalism, and journalists – myself included – often make it seem like major events come out of nowhere. That was the case with Hodeidah in late 2018, when the government and the coalition were barrelling up the Red Sea coast, and suddenly the headlines were all about how devastating a battle for the city would be for civilians.

It’s the same with Marib. For the last month, it has been the place making the news (in so much as Yemen is ever really high on the media’s agenda), while places like Hodeidah, where acute malnutrition among young children is worryingly high, or Taiz, where fighting is raging and children are being killed and wounded, are neglected.

But battles and sieges often take a long time to progress. Troops move, politicians machinate, peace talks make progress in fits and starts and then reverse course. At the same time, prices rise and people have less and less money to eat... Until there’s a breaking point.

Deaths from bombs and guns and cholera and COVID-19 happen fast, but sometimes we don’t see the signposts leading up to the big thing.

This isn’t just true in Yemen, even though as a foreign correspondent it’s easy to fall into the dangerous trap of looking at other countries through a different lens than your own. I’m an American citizen, and recent events that were devastating and felt unpredictable – the storming of the Capitol, for example – had actually been brewing for a long time. There were big flashing red warning signs, and for the most part, they were ignored by those who should have been paying attention.

Perhaps the scariest part of all this is that when you’re right in the middle of it, even if you see disaster edging towards your doorstep, it’s hard to know what to do.

Shortly before we spoke, a camp not far from Mahmoud’s house was hit by shelling. Residents had to escape to yet another camp, which is also underserved by aid, and certainly not home.

It’s likely none of the people there ever expected to end up in such desperate circumstances, without money or a permanent home. They have left behind everything to get to makeshift settlements that are overcrowded and often don’t have even the most basic sanitation facilities, and the vast majority of families using them for shelter are in extreme poverty. As Mahmoud put it: “If they had work, they wouldn’t stay in these camps.”

So many people in Marib have run from home at least once, and they are understandably loath to do it again. From the comfort of my desk, it’s easy to encourage people I know to get out of harm’s way and fast, but I know when I walk out the door I can go back.

With no certainty of where to go or what will happen next, leaving home is now an agonising choice many Yemenis in Marib may have to make once more. Mahmoud said his family discusses what they will do if it comes down to it, and they are divided. He has a big family – including his dad’s two wives and their children and their children’s children – so leaving isn’t easy. They fled to another family home in 2015.

“Yes, it’s scary,” Mahmoud says. “Every few days there are rockets… but we’ve been living in a war since 2015. It has become normal.”

Peace talks are ongoing, as are efforts to stop the offensive, including a plea for a Ramadan ceasefire. People like Mahmoud don’t have the power to alter the course of the conflict, but the warring parties, the war profiteers, the foreign countries that are involved – either explicitly or further in the background – they do have pull.

So if Mahmoud has to flee his home again, we can’t say we didn’t see it coming.