In the coming weeks and months, a group of experts will decide if Yemen, a country the UN has deemed the “world’s worst humanitarian crisis”, is in the midst of, or at risk of, a famine.

Despite a recent stream of statements from aid officials – including last week’s warning from UN Secretary-General António Guterres that “Yemen is now in imminent danger of the worst famine the world has seen for decades” – such a declaration is not a foregone conclusion.

That’s because, although it’s an emotionally weighted and frequently used word, famine actually has a highly complex technical definition that is hard to meet and requires a level of quality data that doesn’t always exist in Yemen, which has been at war since early 2015.

For example, the threshold was not met in late 2018, and that was despite similar cries of alarm, despite the fact that some children were clearly starving to death, and despite the finding that nearly 16 million people were expected to be above “crisis” levels of food insecurity.

Two years later, and after more than five and a half years of war – Houthi rebels in the north are fighting an internationally recognised (but mostly exiled) government and its allies in the south, backed by a Saudi Arabia-led coalition – it seems to many Yemenis that almost everything that could possibly go wrong in one country has done so.

More than 128,000 people have been killed by bombs, guns, and mines, according to the nonprofit ACLED, which collects data on conflict zones. Over 164,000 people have been forced to flee for their lives in 2020 alone, and even when the fighting has occasionally come to a stalemate, there have been cholera outbreaks, water shortages, flash floods, and COVID-19 to worry about.

The economy has collapsed for all but the few who have managed to profit from the war, and the currency has crashed too. Many of those who had savings will by now have exhausted them, meaning more and more of Yemen’s 30 million people are forced to make incredibly difficult choices, such as which family member won’t get to eat on any given day.

That still doesn’t necessarily mean Yemen, or parts of it, are in a capital “F” famine. But it is clearly in the midst of a devastating crisis, one that is damaging for its survivors and will likely impact the country for generations to come.

As one expert on food insecurity put it: “I kind of wish we would stop hyperventilating about [the word] famine.”

Even if you don’t quite breach the thresholds required for a declaration, they said, “it doesn’t mean that people aren’t dying, and kids aren’t malnourished. It just means it is not happening at quite the same pace.”

Sliding down the economic ladder

For Muhammad Mughni, a 43-year-old heavy-set man with a big smile, Yemen’s collapse has meant going from a stable career that provided a comfortable life for his wife and kids in the capital city of Sana’a, to doing odd jobs, skipping meals, and worrying what will become of his family now they have no money left.

Mughni holds a degree in business administration and used to be known as “the money guy” at the English-language Yemen Observer newspaper, where he handled the day-to-day administrative and financial tasks. His salary was cut in half in 2016, the publication shut down in February 2019, and his wife is now out of work too.

Since losing his job, he has made some money assisting a dealer of qat – the mild stimulant leaves many Yemenis chew when they socialise. That gig brought him $3 a day plus a bag of qat for personal use, but the work dried up a few months ago when the weather turned cool, meaning less qat is grown and sold. Now he does other odd jobs, mostly fixing friends’ cars.

The money Mughni brings in isn’t nearly enough to cover the $100-a-month rent for his apartment in a three-storey mudbrick Sana’a neighbourhood, on top of the school fees for his sons. That’s not to mention food, which has become an increasing concern in the Mughni home of late.

He and his wife have used up all of their $1,000 in savings, sold a third of her jewellery, and cut back on just about everything, including what they eat.

The family has changed their eating patterns: Rice and potatoes make up more of their diet than they used to, and gone are the canned beans they had with morning and evening meals. They try to make it up with locally grown beans, which are cheaper but take longer to prepare.

Many items have been axed from their shopping list, including fruit, cheese, tuna, and fish. As for meat, Mughni said, “it’s a rare commodity we can only dream of.” On some days, breakfast and dinner consist of just tea and kaak, a Yemeni biscuit.

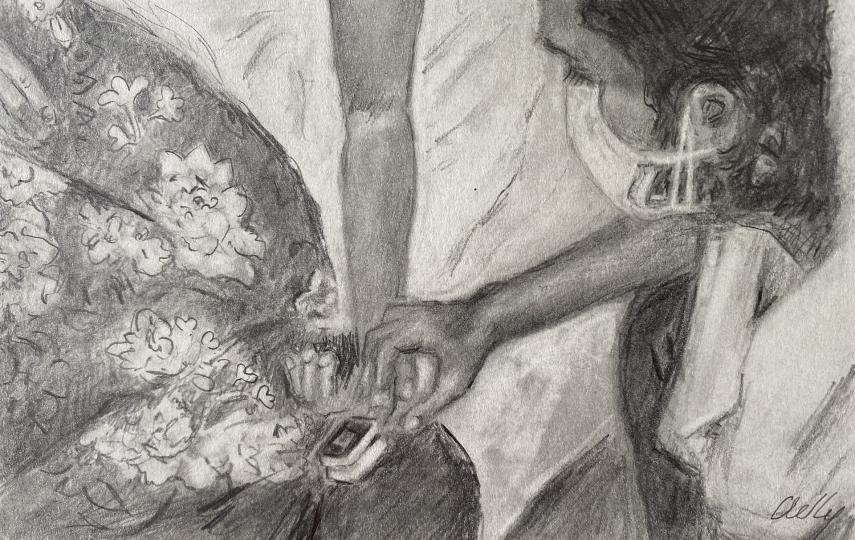

To make sure they can pay rent and keep their kids in school, Mughni and his wife sometimes go without meals. “When worse comes to worst, we prioritise food for the kids,” he said. “See how much weight I’ve lost,” he chuckled, grabbing what was left of his belly with both hands.

Coping strategies

While Mughni jokes about his weight loss – he’s down 20 kilograms since he lost his job – switching to less preferred food options, reducing portion sizes, and skipping meals are all classic “coping strategies” that people resort to when they can’t get enough food. There’s even a “Coping Strategy Index”, one of many tools used to measure food insecurity.

Coping mechanisms like these vary in both frequency and severity, and can include extreme measures like families marrying off young daughters because they are unable to provide for them, a practice that has become a growing concern over the past few years in Yemen.

A UNICEF spokesperson told The New Humanitarian that “the conflict in Yemen has exhausted many families and is pushing them into destitution.” The agency said it had heard “stories of skipping meals, selling household items and many families going into debts, [which are] likely on the increase in a bid to make ends meet.”

Amal Nasser, non-resident economist at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, a think tank focused on Yemen, points out that even before the war only six percent of Yemenis held bank accounts, which offers some perspective on the options most people have when they are forced to draw down on savings.

“It’s a very cash-based economy,” Nasser explained, adding that “savings are not just money in accounts – you can have accumulated capital, houses, jewellery; gold is often seen as security for women and families.”

But “whoever had savings has spent them” by now, she said, adding that many Yemenis are now relying on friends, family, and neighbours to get by. “In Yemeni society, people show solidarity with one another,” she said. “But you show solidarity until you run out of it; you cannot just give when you don’t have anything left.”

Mughni has benefited from some of this solidarity, with people giving him money when they can. But he is still not comfortable approaching his many friends or family members for assistance. “People who helped me did so voluntarily,” he said. “I’d rather die than ask for help. That would render me a mere beggar while I’m still young.”

He’s also probably not yet eligible for humanitarian assistance of the sort given out by UN agencies and NGOs, although Mughni said the family did get some food aid three months ago because his wife had volunteered at a government-run school. In October, the last month for which numbers are available, the World Food Programme said it gave aid to 8.7 million Yemenis, including food, cash, and vouchers. It has had to slash rations because the UN-led response is underfunded, which has led to cuts in other aid programmes too.

An estimated 47 percent of Yemenis lived under the poverty line in 2014, a number that reached a projected 75 percent by the end of 2019, according to the UN Development Programme. Nasser said it is worrisome that people like Mughni, who are not on what we might think of as society’s bottom rung, are struggling to buy food.

“We are not talking about people who don’t have incomes or are listed on humanitarian aid lists since the beginning [of Yemen’s war]; we are talking about the potential for food insecurity in households where people are actually still going to work. That’s very dark. You go to work and you make money, and this money is worthless. It cannot even secure food on the table.”

Money’s worth less, food costs more

Mughni doesn’t get a steady salary, just income from the work he can get, so Nasser’s comment applies even more aptly to Abdul Qadir Muhammad Banafi’, a 61-year-old father of seven who has long held a government job, and who has plenty of space for his large family in a house tucked on a hill in the southern Shabwah province.

He is still employed at the provincial health authority, although like more than a million public employees in Yemen – doctors, teachers, nurses, and local government workers – his salary has not been regular since 2016.

Banafi’ is actually paid most of the time, but he said the $300 a month he gets has lost two thirds of its value since the war began, meaning he’s had to pull his two oldest, now 22 and 24, out of schooling so they can work, stopped buying luxuries that many might consider basics (like soap), and halved the food they buy.

“As war kicked in, the cutdown started,” he said. “In 2020, everything seems to have collapsed.”

The reasons behind the collapse of Yemen’s economy and its currency are many and varied, but recently include a large drop in money sent home from abroad, as expatriate Yemenis suffer the impacts of COVID-19.

The Yemeni rial has been on the decline since mid-2016, when commentators began to warn that Yemen’s Central Bank – then seen as a bastion of stability in a fractious conflict – was running dangerously low on foreign currency reserves.

Now, there are two separate central banks, one allied with the Houthis in the north and one with the government in the south. The southern bank was propped up by an injection of cash from Saudi Arabia in late 2018 – an intervention Nasser and others say would be of clear humanitarian benefit if repeated now – but is running low on reserves again.

The Houthi authorities have banned the use of newer bank notes printed by the southern bank, resulting not only in separate monetary policies but also in divergent exchange rates between the regions.

In short, money is worth less in the south, where Banafi’ lives, than in the north, where Mughni lives. And food prices are up.

When there isn’t enough food to go around, the family makes sure Banafi’, who has hypertension and diabetes, and one of his sons, who has a developmental disorder, eat first.

The Banafi’ family is actually fairly well off in their village, where he is sure some people are barely eating at all. “It’s getting more expensive by the day,” he said.

Banafi’ said the family has received grains from various NGOs, but described the handouts as barely fit for human consumption. Now, when aid groups tell him it’s time to come and collect his rations, he doesn’t show up. “When you see crowds queuing for aid, it feels humiliating for the whole population, like it’s done intentionally.”

That doesn’t mean he doesn’t have help. Family members – mainly expatriates living in neighbouring Saudi Arabia – have sent money. And like Mughni, he won’t reach out for that help, even if he needs it. “They know that I won’t ask for help no matter what, so they offer help without me having to ask,” he said.

Widespread malnutrition

A range of factors – from conflict and displacement to job loss, inflation, price rises, and aid cuts – are forcing Yemenis like the Mughnis and the Banafi’s to eat less nutritious foods, or to skip meals altogether. That can easily tip a person, or a population, into various degrees of malnourishment.

This hits the most vulnerable in society first. As the UNICEF spokesperson put it: “Although famine has not been declared in Yemen, severe acute [short-term] malnutrition remains a major concern… Children suffering from acute malnutrition are susceptible to other diseases and conditions, including anaemia, cholera, and other diseases which increase their risk of death. That’s why urgent treatment is key, and for millions of children our work is thus the difference between life and death.”

There’s also an impact of malnutrition that is difficult to talk about or quantify, but there is evidence that foetal and neonatal malnourishment can impact brain development, and possibly lead to mental health problems.

That possibility has Nasser concerned. “What worries me the most are the long-term effects of food insecurity,” she said. “They could go on for generations. Maybe people won’t die [of hunger], but babies that were born in the past six years are at risk of growing up with various issues. It’s not just about having able bodies, it’s about mental capacities, and of course this will affect Yemeni society in the future… maybe for another 20 or 30 years.”

According to analysis on a limited part of south Yemen released in late October under the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), which the UN and its associates use to make its decisions on famine, over 40 percent of children under five (over 580,000), and more than 240,000 pregnant and breast-feeding women, are estimated to be suffering from malnutrition at present.

The IPC classifies food security in five “Phases”. In most cases, for it to determine that a country – or part of a country – is in or likely to be in Phase 5 (catastrophe/famine), at least 20 percent of households have to face extreme food shortages, more than 30 percent of children younger than five have to suffer from acute malnutrition (measured by weight and height); and at least two out of every 10,000 people have to be dying each day.

The latest data from the north has not been released and collated with that from the south (although sources expect that to happen shortly), so it is hard to say anything for certain about what call will be made.

When Yemen was last said to be on the brink of famine, in late 2018, 15.9 million people – that’s 53 percent of the population – were expected to be above Phase 3 (crisis) in the next year – and that was assuming that humanitarian assistance continued. And no famine was declared.

More attention is certainly paid to mass hunger when the word “famine” comes into play. But Nicholas Haan, one of the creators of the IPC system (which he still plays a key role in), told TNH that the process is actually intended to draw early attention to crises in order to prevent them ever reaching famine status – triggering “strategic [aid] response implications” when populations are highly food insecure but not in Phase 5.

Ideally the media would make a fuss, and donors would kick in money well before the catastrophic Phase 5 arrives, especially because famine declarations tend to come late, after all the sufficient data is compiled.

“We constantly face this challenge… how to get people to react to particularly Phase 3 and 4, before we get to 5,” said Haan, part of the faculty at Singularity University, which aims to expand the use of technology to solve problems. “That's where we try to draw attention to get people to respond.”

Aid bosses are well aware of the classification system and may hope their famine warnings will bring in more money to stop things getting worse, or even help jumpstart peace negotiations.

In the relatively stable province of Shabwa, Banafi’ saw a gloomy future. He has little faith in international aid agencies, and none in the warring parties, which he described as “drenched in treason”.

Nonetheless, his belief in God and in his fellow Yemeni people led him to think his country would not starve en masse. “Where else on Earth can you find a nation that has gone through what has happened in Yemen, where there is no president, no order, no electricity, no salaries, and somehow still managed to survive?” he said. “Ask anyone, and he will raise a finger to the sky and say, ‘God will provide.’”

But with no guarantee where his next meal will come from, Banafi’ remains anxious: “I’m worried about all my family members and, on a broader level, I’m worried about the nation as a whole.”

With additional reporting from Shuaib Almosawa in Sana’a.

as-sa/ag