Violence has returned to northwestern Syria, as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government pushes into rebel-controlled Idlib province, home to some 2.5 million civilians*.

At least 200,000 civilians have now fled the fighting and airstrikes. “The hostilities have escalated intensely, particularly in southern Idlib and northern Hama,” Mari Mørtvedt, a Damascus-based spokesperson for the International Committee of the Red Cross, told The New Humanitarian.

The violence has punctured a tenuous ceasefire agreed by Russia, Turkey, and Iran in 2017 and re-negotiated in 2018. However, external powers are still influential. While Syrians do most of the fighting and almost all of the dying, it is likely the Russians and the Turks who will have the final say over what happens next.

The Astana and Sochi deals

The Idlib region is subject to a complex web of ceasefire deals negotiated between Russia and Iran, which support al-Assad, and Turkey, which backs part of the insurgency.

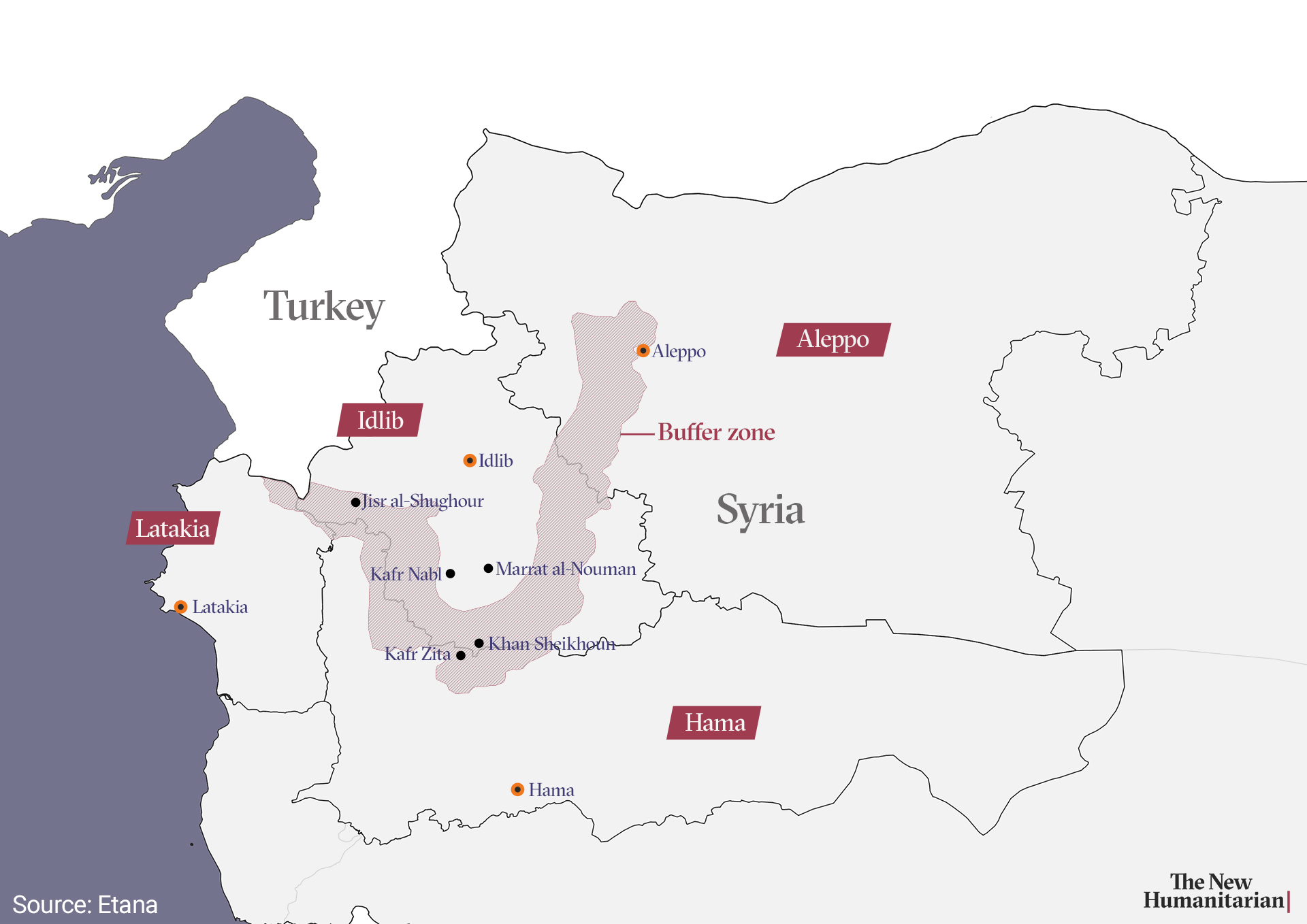

Idlib and parts of the neighbouring Hama, Latakia, and Aleppo provinces are under the sway of a jihadist group known as Tahrir al-Sham. Rival rebels gathered under the National Liberation Front umbrella also operate in the province, with Turkish backing.

After meeting in the Kazakh capital of Astana in 2017, the three nations refer to Idlib as a “de-escalation zone”. Russian and Iranian personnel oversee government compliance with the ceasefire (although Iran’s involvement has faded somewhat), and Turkish outposts monitor the rebel area.

Low-level fighting has waxed and waned to the rhythm of Turkish-Russian relations, punctuated by attempts to spoil the status quo by Syrian hardliners on both sides. But no major offensives have been permitted since winter 2017-2018, when al-Assad’s army retook the eastern part of the enclave while Turkey seized the Afrin area, in an apparent land swap.

The Syrian government’s attempt to launch an offensive in September 2018 was blocked when presidents Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan agreed in Sochi to patch up the ceasefire with a 15-20 kilometre buffer zone, the re-opening of key roads, and joint Russian-Turkish patrols.

The Sochi deal has only been partially implemented and both sides have struggled to keep their respective clients in line.

While Turkey has complained about Russia’s failure to stop the Damascus government from violating the ceasefire, Moscow has accused Ankara of being too soft on terrorist-designated groups like Tahrir al-Sham. Wary of renewed violence in Idlib, Turkey claims to use a softer approach to domesticate the jihadist group by peeling away its less extreme elements.

Turkey’s overriding interest in Idlib is to keep the situation calm, to avoid a “brutal and bloody” military solution that would swell the ranks of the 3.6 million Syrians already in Turkey, said Murat Aslan, a professor at Hasan Kalyoncu University and a researcher with the SETA think tank.

“The major concern is the immigration flow,” Aslan told TNH. “The second aim of Turkey is to keep the regime away from the Turkish borders,” in addition to establishing “a safe zone for civilians” and influencing Syria’s UN-led peace talks by trying to “build a balance” with Russia.

Erdogan also hopes to leverage Idlib to dissuade Russia from engaging with US-backed Kurdish forces in northeastern Syria that are hostile to Ankara.

Russia’s policy is even more ambiguous. Formally, Moscow wants all of Syria to come back under central government control. But, in practice, Russian interests in Idlib “are fundamentally different from those of Bashar al-Assad”, said Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

Trenin said Moscow is determined to prevent jihadist attacks on Russian targets; Moscow recently reported a series of rocket and drone attacks on its Hmeymim air base, about 60 kilometres from the current frontline. But Russia may otherwise be satisfied with bottling up surviving extremists in Idlib, since backing al-Assad in an all-out military reconquest could cause “massive civilian casualties” and trigger a backlash against Russia. “Russia has also been tolerant of Turkey’s apparent failure to fulfil its part of the Sochi agreement,” Trenin told TNH.

For Moscow, he concluded, “maintaining some sort of a status quo in Idlib is preferable to either supporting a Syrian offensive or pressuring Turkey hard on its Sochi commitments.”

Maxim Suchkov, a Middle East expert with the Russian International Affairs Council, noted that the Idlib standoff has offered Moscow “an opportunity to play a big-picture foreign policy game with Turkey”, in which the Tahrir al-Sham dilemma serves as a pressure point to “bring Moscow and Ankara closer together on other issues”.

Renewed violence

As recently as 26 April, Russia, Turkey, and Iran held another tripartite meeting in the Kazakh capital of Nursultan (formerly Astana), where they vowed to “fully implement the agreements on stabilisation in Idlib”, including the joint Turkish-Russian patrols.

Days later, the Syrian government went on the offensive, apparently with Moscow’s blessing.

“The situation in Idlib and other areas where terrorists are still active cannot go on like this forever,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said on 29 April. “We will proceed from the fact that the Syrian government has every right to ensure the safety of its people on its territory.”

Syrian state media says its actions are in response to incursions and violations from opposition forces it describes as “terrorist”.

Turkey initially kept a low profile, leading to speculation about another Russian-Turkish land swap (on 4 May, Ankara-backed rebels reportedly seized two Kurdish-held villages near Aleppo) or an attempt to forcibly impose the joint patrols.

“Moscow is pressing harder for more robust action, both because it feels the situation there is spinning out of control and Tahrir al-Sham is consolidating its positions, and because the Russians are under pressure from the Syrians and Iranians for failing to make Turkey do what it once promised,” Suchkov told TNH. However, he said Russia’s demands for “joint patrols, peace talks, and measures to curb Tahrir al-Sham” have been chosen with “sensitivity to Turkish positions” as realistically achievable interim goals that can avoid a head-on conflict with Ankara.

Sinan Hatahet, an Istanbul-based Syrian analyst, also viewed the Kremlin’s support for a new offensive as an attempt to “exercise some pressure on Turkey”.

He said likely targets included Jisr al-Shughour, the Ghab Plains, and northern Hama – an area he considered “low-hanging fruit” given its limited population compared to other parts of Idlib, the low risk of stumbling into Turkish outposts, and the fact it houses many non-Syrian jihadists seen as a threat even by pro-opposition nations.

“The most likely scenario is some land-grabbing in western Idlib and northern Hama up to the Orontes river,” Hatahet told TNH. “This would include Qalaat al-Madiq, Jisr al-Shugour, and all of the Ghab Plains.”

Qalaat al-Madiq was captured by loyalist forces on 9 May, at which point Turkey’s position appeared to harden. The following day, Defence Minister Hulusi Akar accused al-Assad’s regime of trying to alter the lines drawn up in the Astana process and said Turkey expected Russia to “take effective and decisive measures” to stop the offensive.

The effects of a full-scale military assault on the wider region have been predicted as a “nightmare” and the “worst humanitarian tragedy of the 21st century” by senior UN officials.

Civilians in the line of fire

A recent survey by REACH, a UN-backed initiative for humanitarian reporting, cites local estimates that the southern part of the opposition-controlled enclave (which includes southern Idlib and northern Hama provinces) may hold as many as 620,000 inhabitants, 140,000 of whom are displaced from elsewhere.

Even in the absence of major advances in the fighting further north near Jisr al-Shughour, 200,000 people are estimated to be on the run.

“In Hama, families have been seeking temporary refuge while others are on the move in Idlib Governorate, reportedly moving towards camps close to the Turkish border and also western and northern rural areas of Aleppo Governorate,” said Mørtvedt. “The population movements are continuous and difficult to track.”

Rights groups and UN officials say the tactics used by Moscow and Damascus are causing extensive harm to civilian welfare, and note a series of attacks on medical clinics and schools, as well as heavy, indiscriminate bombardment of civilian areas. Aid workers have been killed, and relief operations, schooling, and social services widely disrupted.

The effects of a full-scale military assault on the wider region have been predicted as a “nightmare” and the “worst humanitarian tragedy of the 21st century” by senior UN officials.

Shelling by opposition forces has also killed civilians and “hit residential neighbourhoods and refugee settlements in Hama governorate and Aleppo city,” according to Marta Hurtado, a spokesperson for for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

However, the government air campaign appears to be causing most damage.

“The attacks against hospitals in Syria are a crime against humanity.”

Amnesty International accuses the Russian and Syrian militaries of waging “a deliberate and systematic assault” against Idlib’s health sector, and UN officials say 18 different medical facilities were attacked between 29 April and 17 May.

Several of the clinics bombed were enrolled in a UN-run mechanism for “humanitarian deconfliction”, which lets hospitals, schools, and other civilian sites add their data and coordinates to a “no strike list” that notifies all armed actors of their location and protected status.

Mohamad Katoub, a Turkey-based official with a medical NGO, the Syrian American Medical Society, told TNH his group lost three “deconflicted” clinics in early May.

“This has been such a consistent pattern in the past; these attacks against hospitals are widespread and systematic,” Lynn Maalouf, Amnesty’s Middle East research director, told TNH. “This is what brings us to say the attacks against hospitals in Syria are a crime against humanity.”

Stressing that more than 170,000 civilians now lack medical assistance, UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock admitted the possibility at the UN Security Council that the no strike list could be used, perversely, to find and destroy hospitals.

Russia’s UN envoy Vasily Nebenzia rejected Lowcock’s accusations “point blank”, and the Syrian UN representative, Bashar al-Jaafari, was equally dismissive.

“There are no arbitrary attacks on civilian Syrian citizens in Idlib; there are military operations by the Syrian Arab Army and its allies against a terrorist entity,” Jaafari said.

A ceasefire in return for joint patrols?

On 13 May, Erdogan called Putin, reportedly warning him that al-Assad’s actions were jeopardising “Turkish-Russian cooperation”. Russia and Turkey have since set up a joint committee to handle Idlib in line with the Sochi deal, and senior officials talk regularly.

According to the Damascus daily al-Watan, a 72-hour truce announced by Russia on 18 May aimed to let Russian and Turkish monitors regroup while “terrorist groups” withdrew into Idlib.

For lack of broader agreement, Russian and Turkish actions may be converging on a plan to launch the joint patrols inside the buffer zone that were previously agreed in Sochi, as a way to calm the situation, shore up their control over Idlib’s insurgent groups, and reduce the chances of a rapid and unpredictable escalation that would cause a deeper rift between them.

So far, however, there’s not enough common ground for a new status quo to stand on, and the fighting may be harder to stop than it was to start. Both sides in Syria have accused the other of violating the truce, and some of the National Liberation Front groups reportedly refused to cease fire unless loyalist forces agree to pull back from Qalaat al-Madiq and other towns.

Neither al-Assad nor his enemies are easily steered or stopped, but Russia and Turkey still appear to hold the upper hand over Idlib’s future – as long as they can agree on what to do.

(*Population statistics in Syria are uncertain and humanitarian sources have in the past overstated numbers in rebel-controlled regions, but there’s no disputing that many vulnerable civilians live in Idlib. Major aid agencies estimate there are as many as 2.5 million people in the wider Idlib region, an area that includes parts of the Idlib, Latakia, Hama, and Aleppo provinces but not Afrin or areas further along the Turkish border.)

(TOP PHOTO: A woman stands amidst the rubble on 20 May after an airstrike hit the rebel-held town of Kafranbel in Syria's Idlib province.)

al/bp/ag