In two weeks, a deal brokered by Russia and Turkey that has so far held off a government offensive on the rebel-controlled Idlib region in northwestern Syria will come into effect. It could avert deepening a humanitarian crisis for millions already living in difficult conditions. But public details about the agreement – reached in the Russian city of Sochi with no Syrians present – are few and far between. So what do we know, and will it work?

Fearing mass displacement and further violence, humanitarians have met the 17 September announcement out of Sochi with guarded optimism, even as they express uncertainty about the outlines of the deal and its chances of implementation.

“The news of an agreement between Russia and Turkey offers relief, but only in so far as it will avoid a bloodbath in Idlib,” wrote Rachel Sider, a policy advisor for the Norwegian Refugee Council, in an email to IRIN.

Sider pointed out that many previous ceasefires in Syria have collapsed, and warned that even with a deal in place the humanitarian situation in Idlib and the surrounding areas – home to as many as *2.5 million people – remains grim, citing “severe water shortages and displaced families sleeping out in the open.”

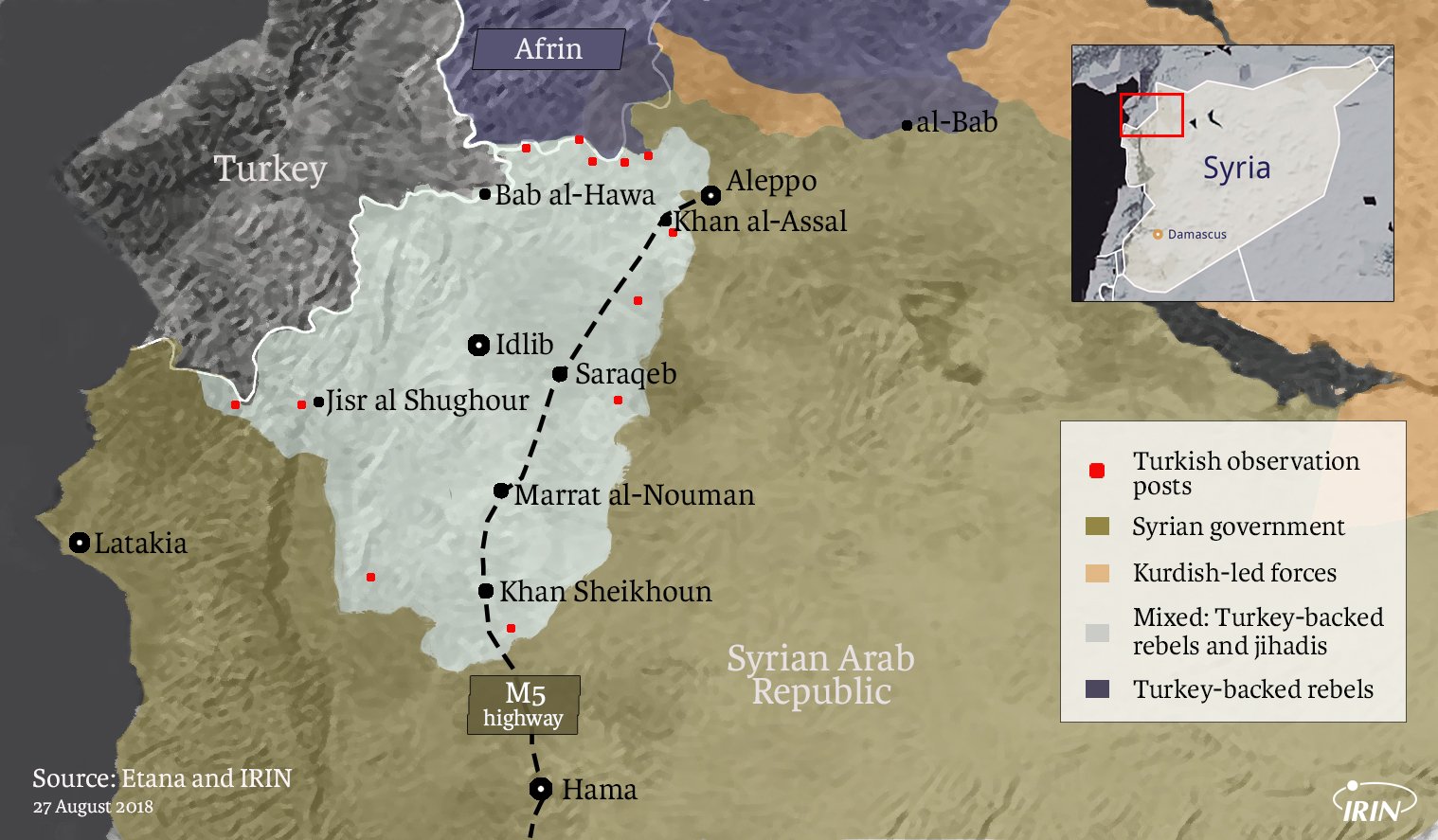

According to the published memo outlining the Sochi agreement, a demilitarised zone of between 15 and 20 kilometres will be established in Idlib province. No heavy weapons – such as tanks or howitzers – will be allowed inside that area.

The deal further stipulates that all “radical terrorist groups” will be “removed” from the buffer strip by 15 October and the zone will then be monitored jointly by Turkey and Russia, though Russia will reportedly not maintain an on-the-ground presence there.

Last but not least, two key highways that traverse Idlib – the M4, which connects Aleppo to the Syrian coast, and the M5, which links Aleppo to Hama, Homs, and Damascus – will be reopened for traffic by the end of 2018.

Aside from these key points, the particulars of what was decided in Sochi have yet to be fleshed out or made public, including where exactly the zone will be and who will be allowed to remain in it. “The agreement itself is a bit ambiguous,” said Sam Heller, a senior fellow with the International Crisis Group.

So, as with so many other deals in Syria’s seven-and-a-half-year war, the devil will be in the detail.

What do the Syrians say?

That the announcement came out of a handshake between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is no surprise: the former’s support for President Bashar al-Assad’s government and the latter’s backing of al-Assad’s rebel enemies long ago pulled any real negotiations out of Syrian hands.

While Putin is supportive of al-Assad, he also wants to keep Turkey engaged in Russian-directed peace talks and maintain positive ties between Moscow and Ankara, in the hope of prying this important NATO member away from the EU and the United States.

As for Erdogan, his chief concern is to avoiding further fighting in the region, both in order to save Turkey’s rebel allies and out of fear of a massive refugee crisis flooding across his borders.

While there was no Syrian presence at the negotiating table, buy-in from all the forces on the ground will be key if the buffer zone is to hold or even come into effect in the first place.

At least for al-Assad’s part, this appears to be the case. The Syrian Foreign Ministry welcomed the agreement, noting that the diplomatic process must ultimately aim to rid “all of Syria’s soil from terrorism and terrorists as well as from any illegitimate foreign presence.”

The rest of the pro-Assad camp quickly got on side, with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif saying “diplomacy works”.

What do the rebels say?

Two major rebel factions dominate in the Idlib region: a pro-Turkey coalition called the National Liberation Front (NLF) and Tahrir al-Sham, a jihadist group that grew out of the Nusra Front, formerly al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch. Tahrir al-Sham controls key parts of Idlib, including the provincial capital and the Bab al-Hawa border crossing.

The NLF issued a statement on 22 September that lavished praise on Erdogan and said Syrians in Idlib welcomed the Sochi agreement with “great relief”. However, the group warned it would “keep our fingers on the trigger” to guard against treachery on the part of “the Russian enemy”. The NLF has since warned that it will not tolerate Russian patrols inside the buffer zone.

Heller told IRIN that while “at first glance [the NLF] looks intransigent,” he believes the coalition’s initial statement “likely signals their cooperation on implementing [the deal].”

“It seems the deal doesn’t require any of the NLF’s [member factions] to actually withdraw [from the buffer zone] or even to surrender their heavy and medium weaponry, just to relocate those weapons beyond the demilitarised buffer,” a move it looks like the NLF will be willing to make, Heller said.

To persuade fighters working under the Tahrir al-Sham umbrella to either withdraw or join Ankara-controlled rebel units, Turkey will likely have to wield both carrot and stick.

What’s less certain is how other groups present in the area likely to become the buffer zone will react come 15 October. While no groups are mentioned by name in the documents published so far, the Sochi agreement is understood to take aim at the NLF’s jihadist rival Tahrir al-Sham and other terrorist-designated factions.

Tahrir al-Sham under pressure

So far Tahrir al-Sham has taken an ambiguous stance, giving no clear indication if it will comply with the deal or try to wriggle out of it. The group clearly worries that accepting Turkish diktats would weaken its position, but also that rejection could draw a Russian-backed offensive by the Syrian army – or a Turkish-backed attack by the NLF.

Heller said he expects Turkey to try to push Tahrir al-Sham out of the demilitarised buffer by 15 October.

To persuade fighters working under the Tahrir al-Sham umbrella to either withdraw or join Ankara-controlled rebel units, Turkey will likely have to wield both carrot and stick.

Veteran jihadists and foreign fighters dominate Tahrir al-Sham’s leadership, but much of the rank and file are young local men who may be more interested in their families’ survival than ideological principles. According to the Syrian pro-opposition newspaper Enab Baladi, one faction of Tahrir al-Sham has already signalled its readiness to withdraw from the buffer zone, over the objections of a more intransigent rival wing.

While the Sochi-friendly members of Tahrir al-Sham are being courted by Turkey, their rejectionist rivals are supported by smaller jihadi groups like Hurras al-Din, a Tahrir al-Sham splinter that has positioned itself on the most extreme fringe of Idlib’s politics. Hurras al-Din has already come out against the agreement.

Given that Tahrir al-Sham has fractured before, Ahmed Aba-Zeid, a Syrian researcher and supporter of the non-jihadist opposition, has previously told IRIN he anticipates “additional splits as Turkish pressure on the group to dissolve increases, but this time from its non-ideological contingent.”

A Free Syrian Army-flagged group known as Jaish al-Ezzah has also protested the agreement, raising the heat on radicals in Tahrir al-Sham, who stand to lose face if they bend to Turkey’s orders.

Although several prominent members of Tahrir al-Sham have attacked the Sochi deal in the media, it has issued no public statements as of yet, and the group’s representatives say they are still discussing the matter internally.

Behind the scenes, Tahrir al-Sham appears to be pleading with Turkey to water down the demands placed upon it, or to help find some other face-saving solution.

“Some of this [outward] rejectionist rhetoric may be part of a negotiating pose,” Heller noted.

A Tahrir al-Sham spokesperson did not respond to IRIN’s request for comment.

Turkey’s options, Russia’s decision

Rebel infighting could be as devastating for Idlib’s civilians as a Russian-backed Syrian army offensive, and may spark unpredictable splits and fissures on both sides of the divide.

Should Turkey fail to get Tahrir al-Sham to comply, or if some faction of the group tries to obstruct implementation of the Sochi deal, it’s possible Ankara will shift gears and support an NLF attack against Tahrir al-Sham, Hurras al-Din, and other jihadist rejectionists.

Rebel infighting could be as devastating for Idlib’s civilians as a Russian-backed Syrian army offensive, and may spark unpredictable splits and fissures on both sides of the divide.

Aware of the distaste most Syrians feel for foreign-inspired infighting, Tahrir al-Sham is already doing its best to appeal to a shared sense of hostility against al-Assad and the Russians.

“Dividing the factions between moderates and terrorists and making them strike each other is a stratagem of the Russian occupation,” warned Tahrir al-Sham’s online news agency, Iba, in a 25 September statement distributed across Syrian social media.

The following day Erdogan insisted that the withdrawal of “radical groups” from Idlib’s demilitarised zone was already underway. But the Turkish president provided no detail and so far there’s little evidence of movement on the ground.

As things stand, the stalemate seems unchanged: Turkey keeps prodding Tahrir al-Sham to play by the Sochi rules and Tahrir al-Sham is still trying to bridge its own internal divides.

With only two weeks left to go, it’s unclear if Erdogan can implement his side of the Sochi deal – or at least persuade Putin that whatever the situation is like on 15 October, it’s better than a battle.

It’s a holding pattern for humanitarians too, with the UN estimating that as many as 800,000 people could be displaced by an offensive.

“Any solution that removes the immediate threat of military action is welcome,” Cynthia Lee, a Damascus-based official with the International Committee of the Red Cross, told IRIN. “We now have to wait and see how the announced ‘demilitarised zone’ around Idlib will be implemented.”

(*Population statistics in Syria are uncertain and humanitarian sources have in the past overstated numbers in rebel-controlled regions, but there’s no disputing that many vulnerable civilians live in Idlib. Major aid agencies estimate there are as many as 2.5 million people in the wider Idlib region, an area that includes parts of the Idlib, Latakia, Hama, and Aleppo provinces but not Afrin or areas further along the Turkish border.)

This work was supported in part by a research grant from The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation.

al/as/ag