Millions of Syrians haven’t had enough fuel to cook their food and heat their homes this winter.

Syria’s severe fuel shortages have had far-reaching knock-on effects, including a rise in food prices, driven by higher transport costs and currency depreciation in government-run areas that had largely avoided such economic hardship. According to the UN, two thirds of Syrians live in “extreme poverty” and 90 percent spend at least half their income on food, so there’s limited ability to cope with these price hikes.

As frustration over the state’s inability to solve the shortages mounts, so does discussion of who or what is to blame. Syrian authorities accuse Western nations of “economic warfare”, while US and EU diplomats say the regime of President Bashar al-Assad is responsible. Experts tend to point to a combination of economic malfunction, corruption, and Western sanctions.

Over the past eight years of war, it has rarely been easy for Syrians to get the fuel that powers electricity plants, factories, hospitals, gas stoves, and home heaters. As Myriam Youssef, a Damascus-based researcher with the London School of Economics, wrote in February, “like many winters past, our days are drained by hours upon hours of waiting… we wait for fuel distribution vehicles to pass by our neighbourhood so that we buy a few litres, enough to warm the house for a couple of hours.”

But in the last few months, the fuel shortages and related price hikes in parts of the country controlled by al-Assad have become unusually severe. As a cooking gas cylinder in Damascus hit 8,000 Syrian pounds ($15) in January on the black market – more than three times the official price – Baath Media, a news site run by al-Assad’s ruling political party, showed long lines of people waiting for gas in the southern city of Izraa.

Even members of Syria’s rubber-stamp parliament, who have some leeway to discuss economic issues, complained about the gas crisis in their January session. Parliamentarians mostly blamed Western sanctions, but some also condemned corrupt officials – without naming names.

Industry collapse, new sanctions

Experts say this winter's scarcity is largely the result of new US sanctions, both related to President Donald Trump's withdrawal from the 2015 Iranian nuclear deal and to targeted measures against Syria's oil trade.

This hit at one of the main ways the Syrian government gets its oil, after domestic production was decimated by sanctions and war: Iranian shipments through the Red Sea, paid for with Iranian credits.

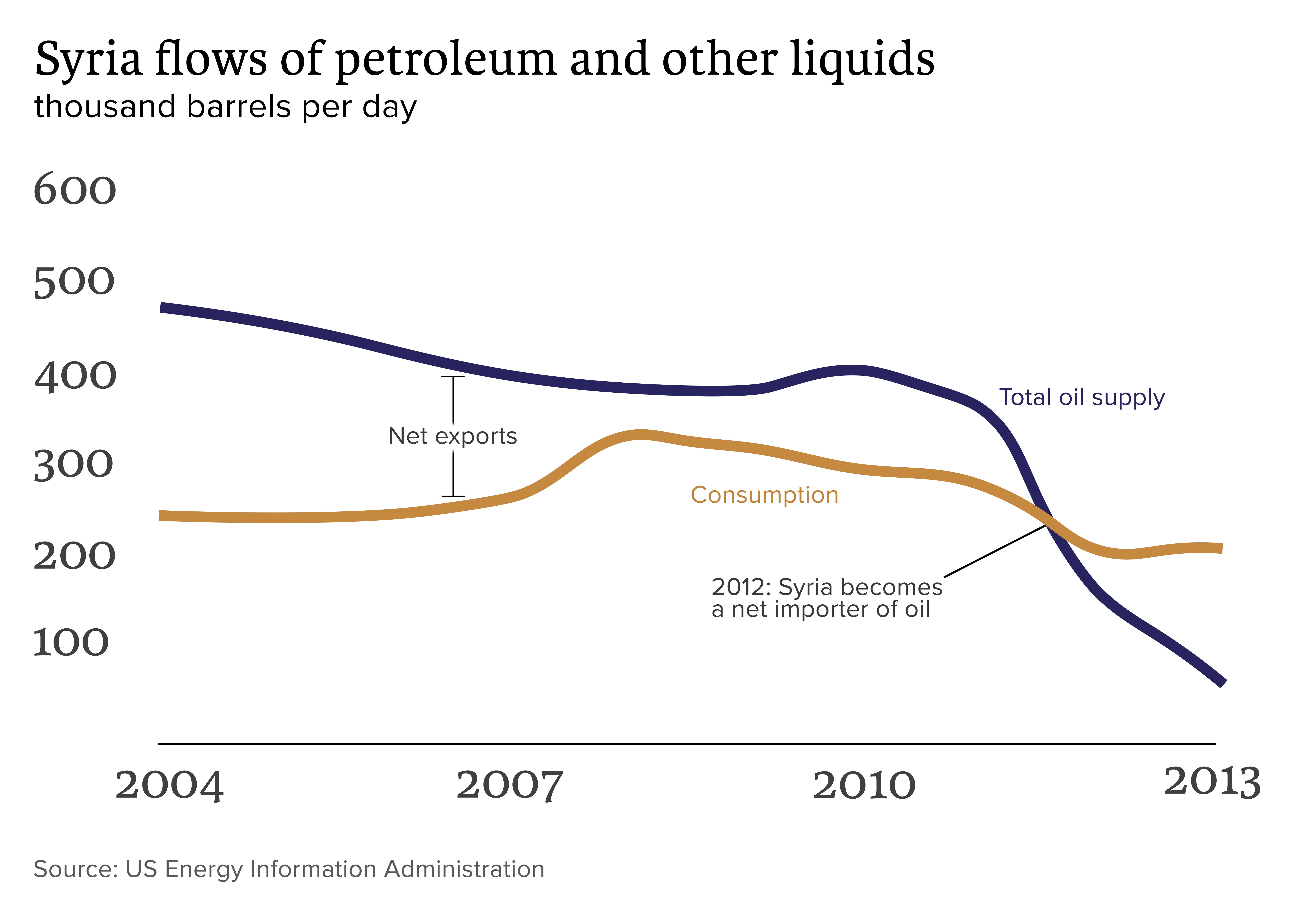

The United States and the European Union both banned the purchase of Syrian oil after al-Assad began a violent crackdown on protesters in 2011, while also sanctioning regime-linked individuals. The EU had taken in 95 percent of Syria’s crude exports before the outset of the war, so its September 2011 embargo hit the country’s oil industry hard, and much of what remained collapsed in subsequent years due to conflict, looting, and a breakdown in maintenance.

David Butter, a Middle East energy expert with the Chatham House think tank, told IRIN that according to official figures, Syria’s crude production has tumbled from a pre-war output of 385,000 barrels per day to around 24,000 today. With local consumption in government-held Syria at an estimated 125,000 barrels per day, that leaves a shortfall of more than than 100,000 barrels daily.

The 5 November re-imposition of sanctions on Iranian energy and shipping assets meant that Iranian oil tankers could no longer buy insurance on the international market. They were followed by a 20 November warning from the US Treasury Department that it would “aggressively target” shipping companies if they continued to carry oil for the Syrian government.

According to Butter, the 20 November notice, which targeted “the entire supply chain for fuel sales to Syria,” had an instant impact. Many of the oil tankers that serve Syrian ports appear to have responded by pulling out of the trade altogether.

Jihad Yazigi, a Syrian economist and editor-in-chief of The Syria Report, also told IRIN the warning was “the main factor behind the recent shortages,” but added that it was important to take into account that demand for energy and oil products has been high because of the winter season.

Even after the loss of much of the tanker trade, there is still some oil coming in on trucks from the Kurdish-held northeast. This supply is organised by regime-linked middlemen who have bargained for access to oil wells controlled – at various times – by Western-backed rebels, the so-called Islamic State, and US-backed Kurdish fighters.

Butter estimates that this trade makes up around 20-30,000 barrels per day of crude oil – much less than the country needs.

Oil and the economy

The oil and gas shortages have hit both individuals and the wider Syrian economy.

Idriss Jazairy, the UN Human Rights Council’s rapporteur on sanctions, reported last year that the US and EU oil embargoes had “dramatically raised the cost of fuel oil for heating, cooking, and lighting,” noting that the state’s gradual reduction of subsidies since 2011 had further impoverished Syrians, and that fuel shortages have second-order effects on the wider economy.

“Iranian oil supplies to Syria play an important role not only in the sense that they supply oil products to the Syrian economy,” Yazigi explained. “They are also a major source, if not the main source of revenue for the Syrian government.”

Since Damascus purchases oil from Iran on credit, the state gains from sales to citizens even when prices are subsidised. That makes oil an important revenue source, which, Yazigi said, “both enables the government to fund its war effort, if you want, but also government and public services.”

Despite this trickle down impact on citizens who live under government control, European diplomats defend the sanctions. They told IRIN the Syrian oil sector is sanctioned because the government uses fuel for military purposes, such as to run helicopters that drop barrel bombs, and point out that there are exemptions for humanitarian purposes.

They reject the suggestion that EU sanctions are responsible for civilian suffering.

“It’s a much broader political economy that has caused those fuel shortages, or that determines who is having shortages and who doesn’t”, said one European diplomat, who spoke to IRIN on condition of anonymity.

“There are people in Syria who have got plenty of access to what they need”, the diplomat said, pointing to the fact that people close to the regime do not appear to have been impacted by the shortages. “The EU can only control what it can control.”

A diplomat from another EU member state insisted al-Assad’s government only has itself to blame for Syria’s predicament this winter.

“The regime takes every opportunity to paint the picture that the EU and the ‘West’ is responsible for the suffering of the Syrian people”, this diplomat said. “However, the regime continues to wage war on its own population, adding to the massive suffering it has already caused.”

An EU spokesperson told IRIN the sanctions, both on regime-linked individuals and on oil, are “a clear signal that the repressive policies of the al-Assad regime against the civilian population of Syria, including the expropriation of land for political purposes, as well as the production and use of chemical weapons, are considered unacceptable by the EU.”

The spokesperson said the al-Assad regime must “change its behaviour and contribute to a lasting settlement of the conflict.”

The US State Department did not respond to IRIN’s requests for comment.

What next?

Syrian authorities have repeatedly promised that the crisis is about to be resolved, advertising a series of high-level meetings, police raids, and emergency measures to combat waste and corruption. That may be easier said than done given the involvement of top regime figures in the illicit economy.

A new rationing system allows citizens to buy their allotted 450 litres of subsidised gasoline using a “smart card” that keeps track of purchases. But the rollout has been marred by problems, adding to the frustration of Syrians forced to wait in lines for fuel.

In January, a Damascus official announced that an old, parallel distribution network for public sector employees would be shut down. In a hint at government corruption, he said it had incentivised officials to request “large quantities” that were distributed in an “unclear” manner. The following month, the government also ended a decades-old state monopoly on cooking gas imports.

Fuel needs will soon be reduced with warmer spring weather, but as the US Congress discusses more comprehensive sanctions, Syria’s oil and gas shortages are unlikely to go away any time soon.

(TOP PHOTO: Ghada, 12, lights a fire to cook at her home in Aleppo this January. Khudr Al-Issa/UNICEF)

This work was supported in part by a research grant from The Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation.

al/as/ag