Towns like Langwenda in Kenya’s central Nakuru County still bear the scars of the post-election violence that rocked the country a decade ago. With new polls just six weeks away, could history repeat itself or have the lessons been learnt?

An estimated 1,200 people were killed and more than 600,000 displaced during the disputed 2007/08 presidential election, with most of the violence errupting in the central Rift Valley between the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin, the two largest ethnic groups in the region.

The area has been the centre of bitter land disputes since independence in 1964, with Kikuyu “settlers” accused of appropriating Kalenjin ancestral land.

As Kenya heads towards elections on 8 August, the derelict houses in Langwenda, a small community in Nakuru’s Mau Forest, are stark reminders of that troublesome past that still haunts the country.

“When the violence started, people came to Langwenda and looted this house,” recalled Christopher Towett, a Kalenjin. “They stole the sofa, the television, and other household possessions, and [they] stole our cattle.”

Towett escaped with his family and neighbours into the forest because it was too dangerous to stay put and risk Kikuyu violence. As Kalenjin retaliatory attacks on Kikuyu properties across the valley intensified, he returned to find his house reduced to rubble and his life shattered.

Since then, as part of a government initiative to resettle those displaced by the violence, Kikuyu communities were bought plots of land in Langwenda. “Kikuyus were compensated and given land here, but we [the Kalenjins] haven’t seen anything,” protested Towett. “I had to rebuild my house with my own money.”

Despite this, Towett believes the two communities can co-exist. His son has married a Kikuyu, and children from the two communities play together. “We learnt from the past and we’re very careful now,” he told IRIN. “The Kalenjins and Kikuyus are now at peace. We don’t want to spill blood again.”

Mutual suspicion

But is Towett’s confidence misplaced? After all, the differences between the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin are long-standing, going right back to when European settlers forced the pastoralist Kalenjin from their land and brought in outside labourers, many of them Kikuyu, to work their estates.

At independence, some of the land was redistributed, with Kikuyus the main beneficiaries. In the late 1980s, the Kalenjin-led, single-party government encouraged attacks on Kikuyu communities, seen as the bedrock of the opposition pro-democracy movement. Tensions have been stirred by politicians ever since.

“The land issue, which is always [at the heart of] the structural violence in Kenya, has not been dealt with at all,” said Maurice Amollo, who heads the Kenyan Election Violence Prevention Programme for the international aid agency Mercy Corps.

“There’s a lot of talk, but if you ask me what has concretely been done to make sure that history doesn’t repeat itself, my honest answer is nothing.”

The Kenyan government and civil society groups did undertake grassroots reconciliation efforts after the shock of the 2007/08 violence, but a political alliance between the Kikuyu and Kalenjin in the 2013 election papered over these cracks.

That “lulled many into believing historic foes were on an ‘irreversible’ course to overcoming animosities,” said a recent report by the International Crisis Group. “Yet Rift Valley reconciliation remains superficial,” it noted.

Amollo agrees. “This tension has been suppressed, but not eliminated,” he said. “I think that people are confusing a lack of violent confrontation between the two communities with peace.”

Pastor Joseph Maritim, a church leader in Keringet, a majority Kalenjin town in Nakuru, told IRIN that mutual suspicion still runs deep.

“Politicians stand for their own political mileage,” he said. “If they tell their people that the land was supposed to be theirs but ‘outsiders’ are settling there, they can set communities against one another. That’s why people fight.”

Others from the Kikuyu community, including Julius Oyancha, a church elder in Molo – one of the worst-affected towns in 2007 – also feel the politicians have let them down.

“The politicians and leaders that incited us and led us into violence left us behind with the problems,” Oyancha said. “We lost most of our belongings and our land, and we came to realise what we were told was not good for our community.”

Familiar story

Politicians are once again accused of stoking ethnic violence ahead of the August elections, especially at the county level in the contests for executive governors.

According to the ICG report, seven of 19 counties listed by the National Cohesion and Integration Commission as among potential violence hotspots are in the Rift Valley.

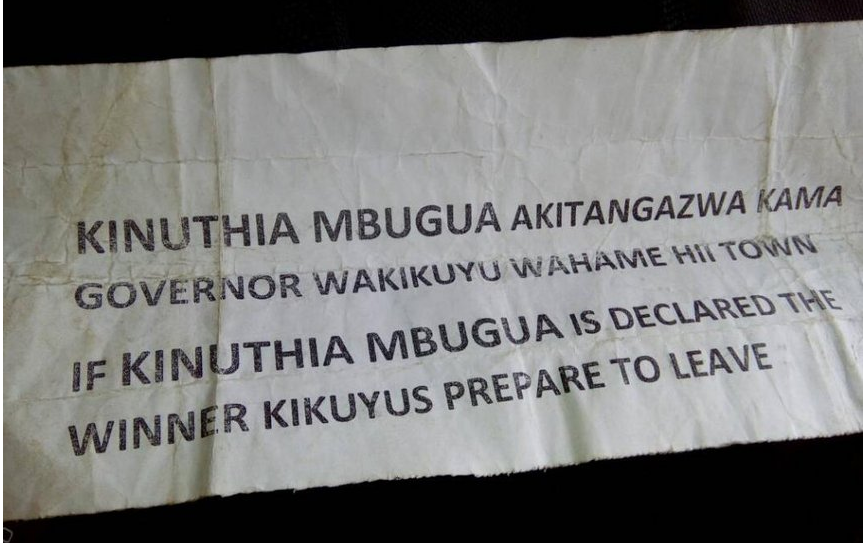

During party primaries in April, leaflets containing hate speech began to appear in Nakuru. They encouraged Kalenjins to cleanse Kikuyu-majority towns in the country should Kikuyu aspirant Kinuthia Mbugua win the Jubilee Party’s nomination to run as governor in August.

In Uashin Gishu, a neighbouring county, Governor Jackson Mandago, a Kalenjin, has explicitly called for Kikuyus to be kicked out should he win in August. With his opponent, Bundotich Kiprop, ahead in the polls, a return to violence in the county remains a real threat.

Though a power-sharing deal under the Jubilee Party is in place between President Uhuru Kenyatta, a Kikuyu, and Deputy President William Ruto, a Kalenjin, it is fragile, argues Murithi Mutiga, a senior analyst at the Rift Valley Institute.

“The fundamental problem in the Rift Valley is that the government has relied too much on a political alliance between elites from the Kikuyu and Kalenjin communities to maintain peace there. A fracture in that pact could obviously lead to instability.”

The pivotal point in that deal will come in 2022, when the Kikuyu are supposed to swing their support behind Ruto. There is unease among some senior Kalenjin that they may not. Failure to do so “almost inevitably would trigger major instability in the Rift Valley”, said the ICG.

Impunity

Kenyatta and Ruto were both indicted by the International Criminal Court for their alleged roles in the 2007/08 electoral violence, but, courtesy of their political pact, they were able to whip up domestic opposition to the court in The Hague. The case was eventually dropped in 2014, a setback that has hurt the fight against impunity.

Most Kenyan IDPs displaced by the many rounds of political violence remain forgotten – without compensation or resettlement. IDPs like Mark Kipkemboi Korir, a Kalenjin, wait in vain. “The Kikuyus went to camps [after the 2007/08 election] and were easily identified and resettled. Because we came to stay with our relatives, it was difficult for the authorities to identify and resettle us,” he explained.

Korir is a member of a lobby group that has found and identified around 1,500 Kalenjin displaced throughout the 1990s who are yet to be resettled, much less win justice through the courts.

“We have written letters for a very long time, but we’ve not heard anything back,” Korir said. Even his personal messages to Ruto have been ignored. “We’ve been left to fend for ourselves,” he added.

The question of impunity, which remains a vexed issue in Kenya, was recently revived by a statement from the ICC that under a more favourable government, it could re-evaluate the dropped cases.

Korir is opposed to such a move. “If the ICC cases are brought forward again, it would open old wounds when we already sat down among ourselves and forgave one another,” he said.

But Mercy Corp’s Amollo, also a Kenyan, believes the perpetrators of ethnic violence must be brought to justice.

“I found it very, very sad that all of the cases at the ICC collapsed. That was a sad scenario because if we had even a handful of people punished that would have changed the way we do our politics in Kenya, permanently.”

He suggested that re-opening old wounds may be the only way to allow proper healing. Otherwise, he said, “it’s just a suppressed conflict that’s waiting for a spark.”

ce/oa/ag

TOP PHOTO: Christopher Towett outside his home