In late April, the German authorities notified Hidayet* and his wife and daughter that their asylum applications had been rejected. They were given one week to leave the country, their home for the past two years.

Three weeks later, German police raided the family’s residence in Hamburg. Nobody was home. With the help of a network of activists and supporters, the family had gone into hiding.

Hidayet and his wife are Roma – a dispersed ethnic minority group that has long faced segregation and discrimination in the Western Balkans. Their families originate from Kosovo, but the couple lived in Serbia before seeking asylum in Germany. Hidayet fears that if he is caught and deported to Kosovo, he will be targeted and attacked.

“I cannot return to Kosovo because in the time of [the Balkan] war, I was recruited to the Serbian military,” Hidayet told IRIN, adding that since he is Muslim and his wife is Christian they are not accepted either by Serbian or Kosovar society.

“I have only one wish: to stay in some place where we could be safe, and this for now is Germany,” he said.

More asylum seekers = more “safe countries”

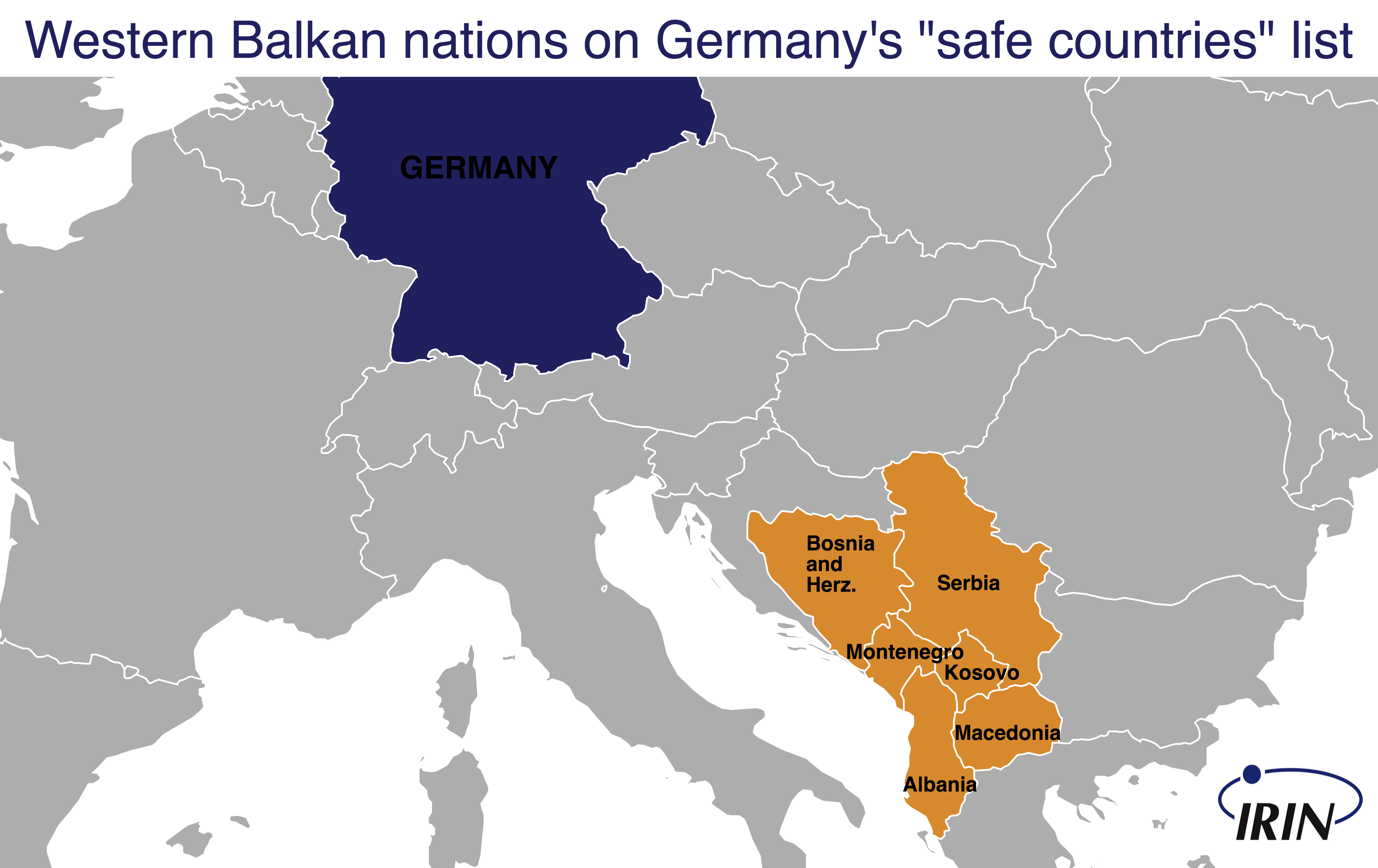

Germany carried out a total of 20,888 deportations in 2015. About three quarters of those were to Western Balkan countries, more than three times the number in 2014. The pace of forced returns has further increased in the first four months of this year, following an amendment to Germany’s refugee legislation last October that added Kosovo, as well as Albania and Montenegro, to a list of “Safe Countries of Origin”. Germany’s “Safe countries” list already included all the other Western Balkan nations outside the EU: Serbia, Macedonia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Designating the Western Balkans as “Safe Countries of Origin” was part of a strategy to address a huge increase in asylum applications in Germany, particularly in the latter half of 2015 when asylum seekers fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere poured into the country.

The German Constitution defines “Safe Countries” as those where in general “neither political persecution nor inhuman or degrading punishment or treatment exists”. Asylum seekers from those countries are channelled into a fast-track process, which critics argue gives them little opportunity to refute the default presumption that, due to their nationality, their claims must be unfounded.

Minorities aren’t protected

Nizaqete Bislimi, a lawyer and activist, says the legislation means that minorities from the Balkans in need of protection aren’t getting it.

“They started to divide the refugees into good refugees and bad refugees,” Bislimi told IRIN, adding that Germany’s refugee laws favour asylum seekers from the Middle East and discriminate against those from the Balkans.

Bislimi, who is Roma herself and was born in Kosovo, has lived in Germany since 1993. She has many friends and clients who have been deported or face the threat of deportation.

Amnesty International’s latest global report found that Roma people in Serbia face discrimination, racial segregation, and limited access to employment, while Roma in Kosovo “suffer institutional discrimination, including in access to social and economic rights”.

According to Professor Albert Scherr, a sociologist at Freiburg University of Education who has done extensive research on Roma communities in Germany and in Eastern Europe, Roma people in former-Yugoslavian countries face not just discrimination and poverty, but open aggression.

“They have no chance at all to live a normal life, to find a job, to send their children to school, to get medical care,” Scherr told IRIN. “It’s an overwhelming situation of discrimination, which does not allow a reasonable life. That's why they come here.”

Past and present

On 3 June in Berlin, a group of protesters demonstrating against Germany’s “Safe Countries” policy marched past the Reichstag building and convened next to the memorial commemorating Roma and Sinti Holocaust victims.

Among them was 15-year-old Victoria Zenkulovic Veselovic, a Serb Roma who arrived in Germany with her mother and brother in 2011. Their asylum applications were rejected and they were assigned a tenuous legal status known as Duldung – which means that deportation is temporarily suspended. Veselovic told IRIN she is afraid to go back to Serbia.

"I hope I stay here because I don't have a future in Serbia,” Veselovic said. “If we go there, I will face discrimination and attacks."

In 2015, Roma people accounted for around 30 percent of all asylum applications from Western Balkan countries, according to estimates from the Ministry of the Interior, but very few were recognised as refugees. Last year, less than one percent of all asylum seekers from the Western Balkans were granted protection status in Germany.

What is persecution?

German authorities have emphasised that the “Safe Countries” classification does not mean that asylum applications by individuals from these countries are always rejected. Tobias Plate, a spokesman for the Federal Ministry of the Interior told IRIN that each asylum application is reviewed individually, and applicants have the opportunity to describe their situation and provide any evidence to back up their claim. “This applies, without exception, to all asylum applicants from safe countries of origin, including members of the Roma ethnic group,” he said.

Plate said the German government was aware of discrimination against minorities in Western Balkan countries, but added that this did not necessarily amount to persecution, which would be grounds for asylum.

“There are no facts that justify the assumption that the situation in the Western Balkan countries forces the Roma ethnic group and other groups of persons to leave,” he said.

But a spokesman with the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, in Germany, Martin Rentsch, said the social, economic, and cultural disadvantages experienced by Roma people in some Western Balkan societies can be considered a form of persecution under the 1951 Refugee Convention. He added that Germany has been upholding its obligation to review every application individually.

The “Safe Countries of Origin” policy appears to be having the desired deterrence effect. In recent months, there has been a steady decline in the number of Western Balkan citizens coming to Germany and applying for asylum.

*Not his real name

yb/ks/ag