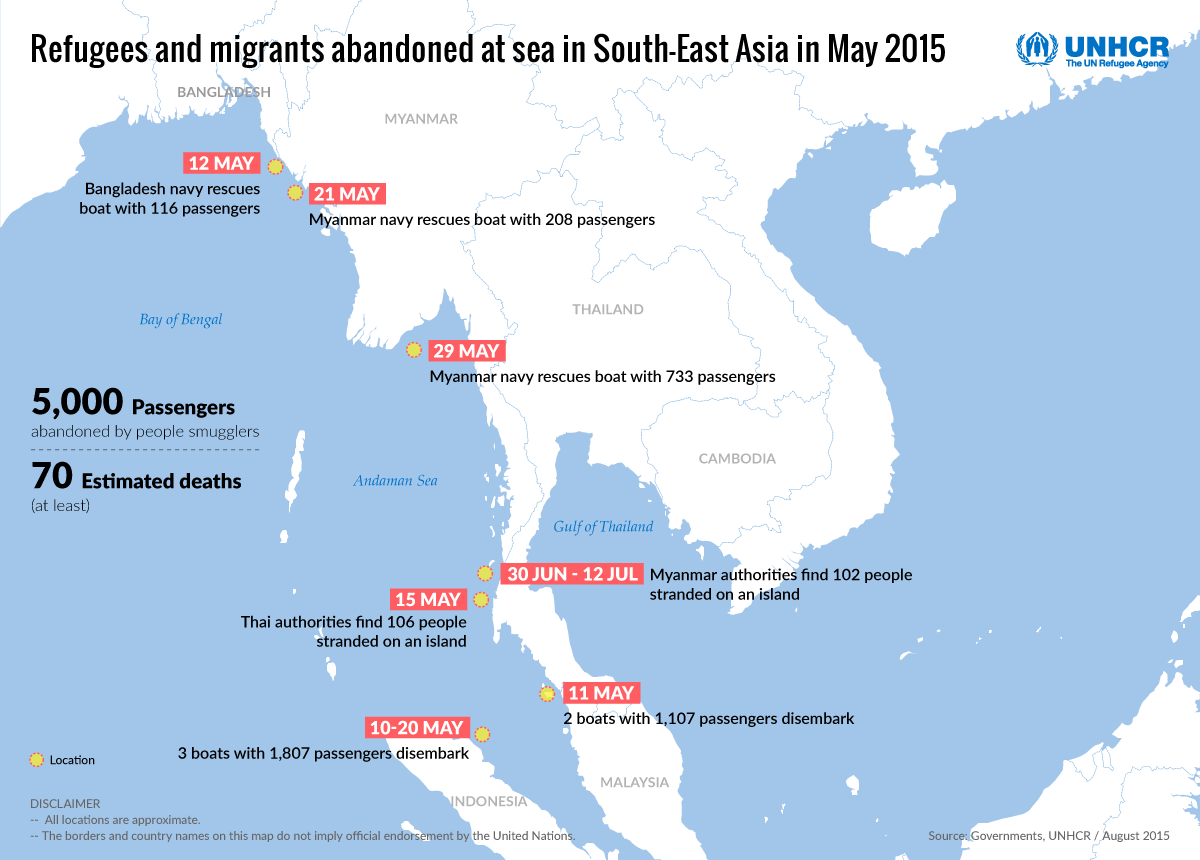

When Malaysia allowed hundreds of Rohingya and Bangladeshi migrants abandoned by their smugglers and left adrift on the Andaman Sea to come ashore last May, it marked the end of a regional diplomatic stalemate that had left thousands of lives in the balance and garnered international headlines.

Nearly a year later, a crackdown has successfully reduced migrant smuggling and trafficking into Malaysia to a trickle. But for hundreds of the Rohingya refugees from Myanmar who came off the smugglers’ boats hoping for a new life, their troubles are far from over and now no one seems to care.

“Malaysia got praised for opening up its borders and allowing them to disembark, but what happened is that the folks that were on the boat were pretty much immediately put into detention."

“Malaysia got praised for opening up its borders and allowing them to disembark, but what happened is that the folks that were on the boat were pretty much immediately put into detention,” explained Amy Smith, executive director of Southeast Asia-based human rights NGO, Fortify Rights.

The Malaysian and Indonesian governments finally agreed to allow the stranded migrants to come ashore but promised them only temporary refuge and assistance. They gave the international community a 12-month deadline to resettle or repatriate the mostly Rohingya victims of the crisis.

The majority of Bangladeshi migrants rescued from the boats opted to be returned home, but more than 370 Rohingya refugees who came off the boats in Malaysia have been held ever since in the Belantik detention centre in Kedah in the northwest of the country. Typically, detainees identified by the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, as Rohingya are judged to have clear asylum claims and released in a matter of weeks.

For months, the government prevented UNHCR, and humanitarian groups, from accessing the Belantik detention centre. By August, when UN staff were finally admitted, many refugees had fallen ill with tuberculosis, said Richard Towle, the UNHCR representative in Malaysia.

“All of that group is still in detention,” Towle told IRIN. “Some have suffered enormously during their journeys to Malaysia and many of them were in poor shape before they left Rakhine State [in Myanmar]. Now superimpose nearly one year of detention — these detention facilities in Malaysia are a tough place.”

TB infections have prolonged the already slow and complicated process of refugee status determinations, and then resettlement applications. Towle explained that resettlement countries won’t accept a refugee until six months after they complete treatment for the infectious disease.

Where can they go?

The United States has promised to resettle an unspecified number of the refugees, while Australia has declined to accept any.

“Australia is not accepting any Rohingya refugees, full stop,” Towle said. “The caseload doesn’t fit within current policy criteria for resettlement, so we have to look further afield for resettlement options.”

The government restricts access to detention centres, but humanitarian organisations and refugees who have spent time in detention described the conditions to IRIN as severely overcrowded and rife with disease.

UNHCR is trying to convince Malaysian authorities to release the refugees and allow them to live in one of the country’s sizeable Rohingya communities, but so far to no avail.

Neither Malaysia nor Indonesia is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, meaning that Rohingya refugees are treated as undocumented migrants with no right to work or access to public services.

The Malaysian government is now working with UNHCR to establish a pilot programme that would allow 300 Rohingya with refugee status to legally work, but for the majority, life in Malaysia remains a struggle.

They live in neighbourhoods like Ampang, where apartments are affordable and an established Rohingya community offers support to new arrivals. But undocumented Rohingya say they can only secure the most dangerous and low-paying jobs. Others spend their days hiding from their smugglers, many of whom live in the same community and demand repayment for debts.

“Unfortunately, the hope of Malaysia falls quite flat,” Smith said. “For Rohingya, it is a very difficult situation because they are basically treated as illegal undocumented migrants and are subject to arrest, exploitation [and] extortion by the Malaysian authorities.”

In Indonesia, most of the Rohingya refugees who had been rescued last May off the coast of Aceh Province in the north have since disappeared from the temporary camps where they were being hosted. They are thought to have put their lives in the hands of smugglers once again in an effort to reach Malaysia and its better prospects for working in the informal economy. It is not known how many successfully made the journey, but some have approached UNHCR’s Kuala Lumpur office and applied for asylum. Towle declined to give specific numbers, but confirmed that “a considerable percentage of the people who finished up in Indonesia have drifted across, under their own devices, towards Malaysia.”

Long-term solution

The Muslim Rohingya have been described as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world. Claiming they are don’t belong to a genuine ethnic group but are Bengali migrants, the government of Buddhist-majority Myanmar has restricted their freedom of movement and denied them citizenship, access to education and the right to vote.

The situation in Rakhine State, where most of Myanmar’s Rohingya population are confined to camps, remains tense, but fewer are choosing to leave. Chris Lewa, coordinator of Thailand-based human rights group, the Arakan Project, believes many are waiting to see if Myanmar’s new government, led by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party, will improve their situation. Others may have been put off by news from Malaysia of frequent immigration raids to catch undocumented migrants.

“The Rohingyas are sort of trapped in Rakhine nowadays,” Lewa said. “However, for the time being, there seems to be less urgency for them to flee due to hope with the new government and due to the deteriorating situation in Malaysia.”

Related stories:

All at sea: what lies behind Southeast Asia's migrant crisis?

Kept afloat by hope: the endless odyssey of the Rohingya

While the first half of 2015 was marked by an estimated 33,600 Rohingya and Baghladeshi migrants taking smugglers’ boats across the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, the highly-publicised crackdown on smuggling networks has reduced arrivals dramatically – UNHCR reported just 1,600 departures in the second half of the year. Others continue to travel overland, crossing the Thai-Malaysian border on foot.

UNHCR estimates that 370 Bangladeshi migrants and Rohingya refugees died during boat crossings during 2015. The remains of more than 220 others were unearthed in people trafficking camps along the Thai-Malaysia border.

The Bali Process, a regional framework set up in 2002 to tackle people smuggling and trafficking, has done little to address the root causes of irregular migration. At a ministerial meeting in March, regional leaders pledged greater cooperation on search and rescue efforts and providing temporary protection and legal pathways for refugees and migrants.

“The Bay of Bengal [crisis] was a wake-up call for the people of the region about the need for greater cooperation,” said Towle. “The Bali Process is a step towards that, but there is still a [long] way to go, otherwise we’ll see another crisis again with the same response as before.”

jv/ks/ag