The night of 10 December began in total calm, even if atrocities committed in the city’s Cibitoke district the week before still loomed large in the minds of many: at least five people had been killed, two of them recently sprung from prison, where they had been held for taking part in demonstrations earlier in the year against President Pierre Nkurunziza’s (eventually successful) bid to run for a third term in office. The authorities had deemed the protests to be an insurrection.

At around 4am, as the sun was about to rise, a crackle of automatic weapons echoed from a military base in Ngagara, and from the Higher Institute of Military Cadres, both in the capital. In the interior of the country, another military base was attacked, according to army spokesman Colonel Gaspard Barazuta.

Come daybreak, bodies again littered the streets. People stayed at home rather than head to work for fear of being caught up in the security forces’ hunt for the “enemies” – the vague term used by the army for the attackers, who were said to have tried to get their hands on weapons and to free prisoners held in Bujumbura’s main jail.

Eighty-seven people were killed during those few hours, among them four soldiers and four police officers.

Some of the bodies, many of young people, were found on Saturday and Sunday on the streets of the Nyakabiga district, some eight kilometres or more from the attacked military bases.

Witnesses said security forces ordered some people out of their homes and summarily executed them – an account repeated by the European Union.

“The young victims were executed at point-blank range, shot in the head. Some were tied up,” said Nibitegeka Cyriaque, a lawyer representing victims’ families.

Security agents “knocked on the door of our house in Nyakabiga,” said one man who fled the country the following day. “They told us to open up, but we refused. A little later we heard explosions in neighbouring houses and even in our house. We heard people screaming, our neighbours, and when we went out, we saw their bodies on the ground in a pool of blood.”

These operations took place in parts of the city known for their opposition to Nkurunziza’s third mandate.

Who was behind the attacks?

On Saturday, one David Nyenyeri, who described himself as a colonel and spokesman for the armed opposition, said such groups would continue to oppose the government with force. Nyenyeri, who was hitherto unknown to most Burundians, did not name the groups in question, but said there were several of them.

He was speaking on Radio Publique Africaine, which has operated clandestinely since it and several other media houses were destroyed after the May coup attempt.

Meanwhile, neighbouring Rwanda has repeatedly denied that it has been recruiting Burundian refugees on its soil into a new rebellion. This charge was extensively set out in a recent report by Refugees International, an advocacy group. It has also been made by authorities in Burundi. Kigali, meanwhile, has long complained that Burundi has turned a blind eye to, or even encouraged, the presence on its territory of members of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a rebel group led by remnants of those who carried out the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. The FDLR has since been based in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, which shares borders with both Rwanda and Burundi.

Aside from Nyenyeri, there has been very little communication from anyone within the armed opposition, and no one to reach out to discuss their motives, ideology or plans.

In June, General Leonard Ngendakumana, among those who staged a botched coup the month before, said from Kenya that he was behind a series of grenade attacks in Bujumbura. He has not spoken out since. The general was one of those targeted by EU sanctions in October.

Slow mediation

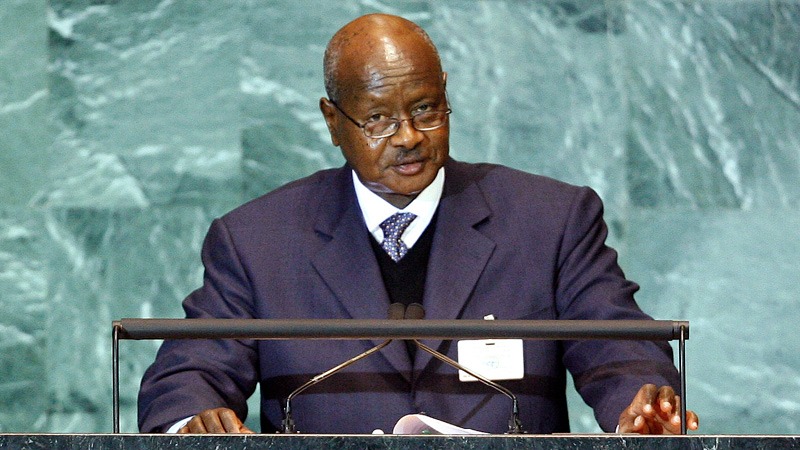

Last week’s bloodshed might well have been avoided had the mediator in Burundi’s crisis, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, fulfilled his role from the start. But the last time he visited this country was in July, a few days before the presidential election. Museveni, himself running for re-election for a fifth term, has since appointed his defence minister, Crispus Kiyonga, to take his place as mediator.

Last week, US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Linda Thomas Greenfield told a Senate panel that Museveni seemed “distracted” by his election campaign.

"Urgent and closely focused attention is needed to quell Burundi's internal conflict, but the East African Community’s efforts to promote negotiations have not borne fruit," she said. "We hope to see dialogue initiated in the very near future. If it is not, and the crisis deteriorates further, possibly into full-scale war, I fear that President Museveni and the EAC could end up being partially blamed, given the lengthy delays in getting the process started."

Ugandan State Minister for International Affairs Henry Okello Oryem responded by explaining that far from ignoring the crisis, Museveni had “kept an eye on Burundi because he receives intelligence briefs on the situation."

Meanwhile, diplomats quoted by RFI radio have expressed doubts over how inclusive the prospective talks will actually be, noting that of the 23 delegates put forward by Uganda to the AU, only two are drawn from the opposition. This failure to bring on board key stakeholders is unlikely to quell the spiralling violence in Bujumbura.

For its part, a coalition of Burundian opposition parties, CNARED, said it had no gripe with Museveni himself, but called for his mediation work to be supported by a panel drawn from the EAC, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, the AU, the UN, the US, former colonial power Belgium and the UK.

The EU has agreed to finance a process of national dialogue, but only if it is fully inclusive.

dn/am/ag