When Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – known as Lula – returned to Brazil’s presidential office in January, he faced myriad intractable challenges: a country still recovering from the deadly coronavirus pandemic, widespread hunger, unchecked police violence, and record levels of deforestation that is rendering some of the country’s farmland unusable and causing devastating floods.

After four years of rule by right-wing, populist leader Jair Bolsonaro, much of Brazil’s progress to combat inequality under Lula’s previous term in office from 2003 to 2010 had been reversed. The country was once again on the World Hunger Map, a measurement of undernourishment worldwide. There was also an increase in homelessness and in attacks against Indigenous people.

Lula campaigned on improving social justice, protecting the environment, tackling hunger, fighting inflation, and protecting the rights and territories of Indigenous people. But the current National Congress is considered one of the most conservative in Brazil's recent history – a leftover from the Bolsanaro era – and is inclined to oppose Lula’s agenda.

In the past three months, experts say that gains in social welfare and Indigenous rights have been significant, but slow.

“Answering the ongoing and urgent humanitarian crises demands a high speed of building and rebuilding structures and institutions that governments, as powerful and complex entities, don’t have,” said Wesley Matheus, a World Bank consultant and director of the Social Development Observatory in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais.

“One hundred days is too little to solve a crisis that comes from a global pandemic, the climate crisis, and four years of neglect,” he added.

Antônio Claret, an expert on poverty reduction in Brazil, said that Lula is relying on programmes that already exist and have been proven to work to chip away at the challenges.

“We don’t always need to innovate on everything. If we are to have perennial public policies that extend across governments, we need to revive – and strengthen – this apparatus,” Claret said.

Local authorities need resources and must be willing to enact Lula’s policies, which lack support in some rural areas, particularly when it comes to indigenous rights, experts said.

“We still have a ruralist bench [in the National Congress] that… wants to see our traditional rights destroyed,” Eric Terena, an Indigenous rights activist, and the co-founder of the Indigenous news organisation Mídia Índia, told The New Humanitarian.

How is Lula trying to ensure food security in Brazil?

Some 33.1 million Brazilians – about 15% of the population – faced some level of hunger during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey conducted by the Brazilian Research Network on Food and Nutrition Sovereignty and Security.

Luiza Dulci, advisor to the General Secretariat of the Presidency, said this was caused by the dismantling of anti-hunger programmes, including Bolsonaro’s decision to end the National Food and Nutritional Security Council (CONSEA) — a measure instituted by Lula during his previous term that is widely credited with reducing hunger in Brazil — when he took office in 2019.

Lula revived CONSEA on his first day in office, and created the Ministry of Development and Social Assistance, Family, and Fight Against Hunger, as well as the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Farming.

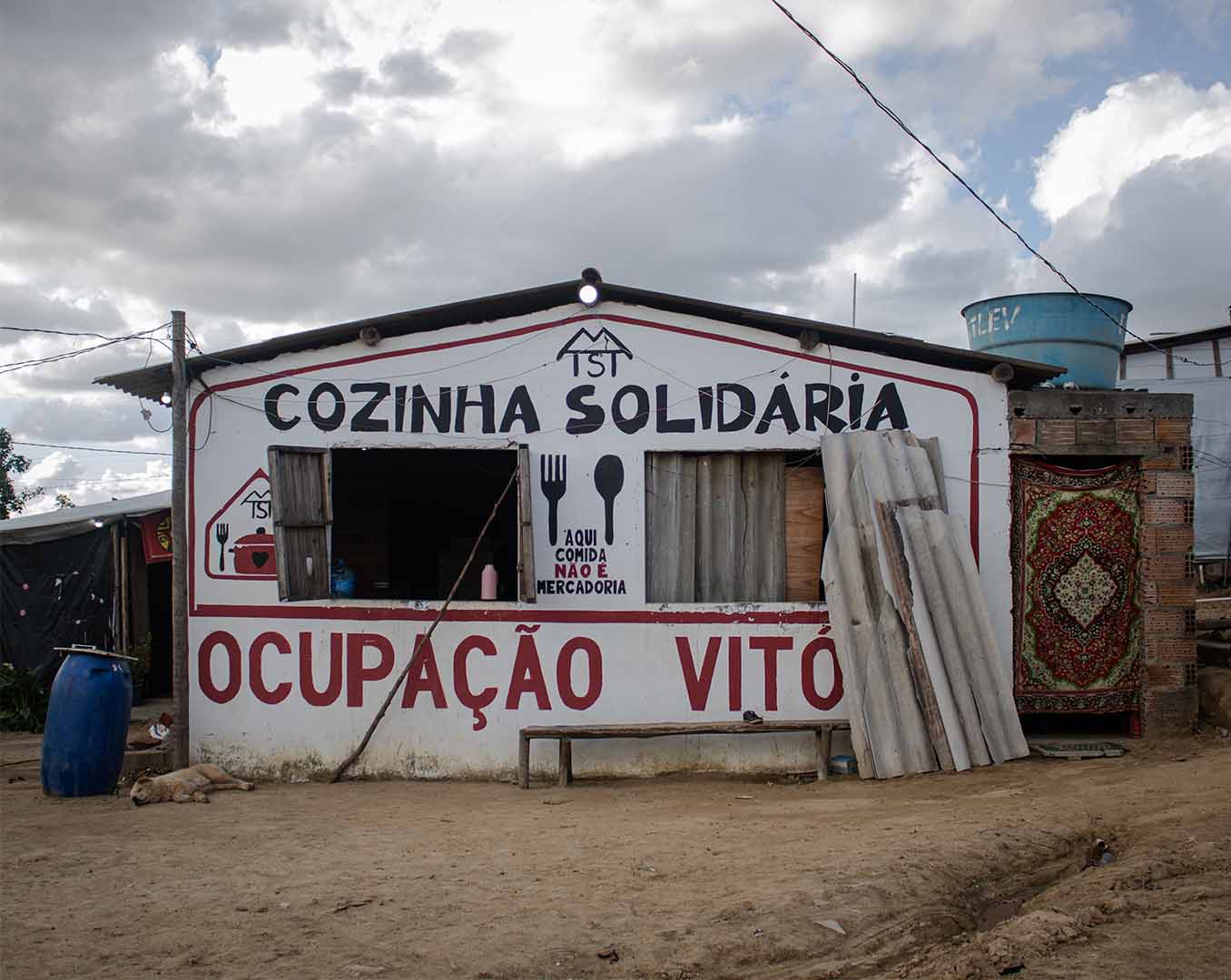

He also restored the Food Acquisition Programme (PAA), which allows the government to buy agricultural goods produced by family farms and provide them to people in need through schools, day care centres, and community restaurants.

Why is Lula extending protections to Indigenous people?

During the Bolsonaro presidency, reports of violence against Indigenous peoples multiplied.The Yanomami, the largest – and a relatively isolated – Indigenous group in the Amazon, saw an estimated 20,000 illegal miners invade their lands, bringing armed conflict, disease, and environmental devastation.

In 2022 alone, malnutrition killed almost 100 Yanomami children, and Greenpeace declared that the group is facing a humanitarian crisis.

The Ministry of Health declared a public health emergency in the Yanomami territory in late January, and since then some 200 illegal mining camps, eight aircraft, and 84 boats used in illicit activities have been destroyed.

In the past two months over 9,500 Indigenous people have received medical assistance, and around 12,700 food baskets will be delivered to indigenous families in May. They will also receive advance payments from “Bolsa Família”, a government social welfare programme.

Despite an 88% decrease in alerts about illegal mining near the Uraricoera River — an area targeted by miners — in other parts of the Yanomami territory that are only reachable by plane, 94 new mining incidents have been reported since 20 February this year.

A letter obtained by Agência Pública, via the Freedom of Information Act, revealed that the Ministry of Defence refused to fix 46 airstrips in the Amazon that are needed to provide quick humanitarian aid to the Yanomami. In January, the mortality rate of children under the age of five on Yanomami lands was still at 1.8 deaths per day. Indigenous leaders believe that military units aligned with Bolsonaro are deliberately stalling the airstrip repairs.

What did Brazil learn from the São Paulo floods?

Torrential rains that hit the coast of São Paulo in February laid bare the unequal impact of the warming climate. Over 60 people died and roughly 2,000 were forced to evacuate their homes, all from poorer families. According to a survey by Brazil’s Civil Defence, the service in charge of disaster responses, four million Brazilians reside in zones at high risk from climate change.

Earlier this month, the Ministry of Integration and Regional Development and Microsoft Brazil launched the ClimaAdapt platform, which identifies regions vulnerable to extreme weather.

But Matheus says these steps are insufficient. “When it comes to climate policy, there is still no clear distribution of prerogatives,” he said.

How is the housing and homelessness crisis being addressed?

Between 2019 and 2022, coinciding with Bolsonaro’s time in office, Brazil's homeless population increased by 38%.

Márcia Melo, national coordinator of the Homeless Workers Movement (MTST), lives in a spontaneous settlement in Diamantina, in Brazil’s southeast. During the pandemic, she says, authorities tried to eradicate the camp, demolishing shacks and cutting the water supply for 30 days.

But Lula’s return to office has changed the dynamic, according to Melo. “MTST has regained a place inside the government,” she told The New Humanitarian.

Lula revived “Minha Casa, Minha Vida”, a subsidised housing programme, earlier this year, and in April the government announced it would deliver nearly 9,000 units by May. The goal is to reach two million units by the end of Lula’s term at the end of 2026.

“The programme depends on city halls to be implemented, and the interest is not always there,” Melo said.

Why is the future of Operation Welcome uncertain?

Since 2018, roughly 426,000 Venezuelans have arrived in Brazil, mostly through the Amazonian state of Roraima. Migrants and refugees are welcomed to the country by military-led “Operação Acolhida” [Operation Welcome]. With Lula expected to restore ties with Caracas, many refugees feel their future is uncertain.

For Ronildo Rodrigues, executive director of Caritas in Roraima, not much has changed in Operação Acolhida over the past 100 days, but there's reason for optimism.

“There has been more dialogue, and we – the civil society – are being heard like we never were in the previous government,” Rodrigues told The New Humanitarian.

In March, a government task force visited Boa Vista, capital of Roraima, to better understand the migratory phenomenon, establish partnerships, and ensure assistance to homeless people.

Yet, it is unclear if Venezuelan migrants will maintain their refugee status. “We still haven’t been given an official position,” said Rodrigues.

Edited by Daniela Mohor and Tom Brady