Last year, 32-year-old Ana Maria* and her four children were forced to flee for their lives after guerrillas entered their village in Tumaco, southwestern Colombia.

“They said they were going to kill us, so I had to take my children and leave. We had to leave immediately; we did not even have time to get our things,” Maria told The New Humanitarian.

Maria’s first thought was to seek refuge in Bogotá. But after finding it too expensive to live in the capital, she and her children ended up in Soacha Alta.

Situated in the barren mountainside above the million-strong city of Soacha, which is on the outskirts of Bogotá, this illegal slum is overrun by criminal gangs hawking drugs to children on street corners.

“I do not feel safe here,” Maria said. “My children are not safe here. I am worried about the micro-traffickers [dealers who sell drugs in small amounts for home consumption] recruiting my children.”

She and her children are part of a new wave of displacement in Colombia, as thousands flee a reconfigured armed conflict that has intensified since the landmark 2016 peace deal that was lauded for bringing an end to Colombia’s 50-year war.

Jozef Merkx, representative in Colombia for the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, explained how the power vacuum left in rural areas by the demobilisation of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) has seen other armed groups battling for a greater share of the lucrative drug and coca-growing trade. They include the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia.

“We are still seeing a number of people fleeing [rural] areas, due to the violence there, especially in areas such as Chocó, Cauca, and Arauca, where groups are fighting for control,” Merkx said.

Read more → In Colombia’s Tumaco, the war isn’t over, it’s just beginning

Colombia has the largest population of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the world – almost 7.7 million people, according to 2018 estimates by UNHCR.

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC) states that about 145,000 new displacements associated with conflict and violence were reported across the country in 2018. And some 40,000 people were newly displaced in the first quarter of 2019 alone.

‘The population is exploding’

Those who flee violence in rural coca-producing regions often head for Bogotá and end up in slums like Soacha Alta.

“Rents are minimal, and it is easier to set up camp there than to try and find proper accommodation [in the city],” Merkx said.

Soacha Alta is classified by the government as an illegal settlement. As Merkx explained, that means there is next-to-no infrastructure – no water mains, no sewers, and only ad hoc electricity siphoned off the grid. Makeshift housing, built without government approval and covered in tarpaulins, sits alongside unpaved streets.

UNHCR works in specific neighbourhoods in Soacha Alta, such as Altos de Cazucá and Altos de la Florida, but could give no official population figure for the settlement as a whole or for displaced people who have fled here since the 2016 peace agreement.

Susana Arévalo, the 30-year-old founder of Fundación Las Pulgas, the only other NGO aside from the UN working in Soacha Alta, estimates that a total of 4,000 families live here now.

“Around 25 to 30 families are arriving every week,” said Arévalo, who lives in Bogotá and has been volunteering here for more than seven years.

People arrive in Soacha Alta with as many as three generations in tow. Entire families survive on less than $100 a month, often sleeping together on the same mattress, said Arévalo.

She was unable to provide figures from before the post-2016 influx, but said: “The population is exploding and the government is turning a blind eye.”

A 2017 IDMC assessment says that 80 percent of displaced people in Colombia live below the poverty line, with one in three living in extreme poverty and in surroundings where “levels of crime and violence are high”.

In Soacha Alta, the post-2016 displaced are considered the most vulnerable. “The new IDPs aren’t settled – they don’t have close community networks; they don’t have resources; they are the ones who are more vulnerable [to drug trafficking],” said Merkx. “They’ve had to leave everything behind and they arrive with nothing.”

Drugs to curb hunger

Maria is one of many mothers here who makes a four-hour round trip to Bogotá most days to find what menial work she can to support her family. “I cannot look after my children,” she said. “I have no choice.”

She often left her eldest child, a 13-year-old, in charge, spending days at work terrified for the safety of her children.

“There is nobody in this town to protect my children while I am at work. We have no water; it is hard to find food. The police will not even come here, it is so dangerous,” Maria said.

Requests to the Bogotá police for comment about the absence of a security presence in Soacha Alta went unanswered by the time of publication.

Arévalo said the precarious circumstances of many post-2016 arrivals offer organised criminal gangs an easy opportunity to recruit children whose families sometimes can’t afford to feed them.

The dealers promise freedom from hunger, either through drug use or by paying the children to smuggle the drugs to neighbouring villages. Locals and community leaders told TNH the police in the area rarely stop and search the children.

“The children don’t have enough to eat here,” Arévalo said. “And so the gangs offer them basuco, to curb their hunger… that’s how they get hooked.”

Basuco is a concoction of base cocaine that is smoked. It is impure and unrefined, then mixed with brick dust, chalk, and paint scraped off walls. It is toxic, but also cheap – one dose costs just 30¢ ($1 is equivalent to 3,308 pesos).

Local charity fills the gap

In 2012, Arévalo founded Las Pulgas – an affectionate Colombian term for small children that literally means “the fleas” – to feed the children in Soacha Alta.

The local charity now has a daycare for 20 children and a kitchen that feeds 70. Aside from feeding and caring for the children, Las Pulgas also runs workshops to teach the children and their mothers about nutrition and how to cook.

“We wanted mothers to know their children would be safe somewhere, so they could go to work,” Arévalo said.

Since Maria discovered Las Pulgas, her youngest two children stay there during the day, and her older two go there after school.

For now, the daycare at least offers Maria some assurance.

“Now there is Las Pulgas, it is better, and I feel less nervous when I go to work. But it is still a horrible situation,” she said.

The conditions in Soacha Alta are not unique.

“Of course, this is happening across Colombia – both with IDPs moving to big cities and micro-trafficking,” said Merkx. “This is happening to all the big cities – Medellín, Cali, all of them.”

For UNHCR, a key part of any long-term, sustainable solution that could offer some protection and stability to residents here and in other illegal settlements is to convince the government to redefine the communities as legal residential areas.

“The government sees these areas as slums, but if they were actual towns, the government would be forced to take responsibility to provide basic services,” said Merkx.

Compensation and reparation

Maria does not currently receive aid from the government but could apply for it.

The 2011 Victims and Land Restitution Law, commonly referred to as the Victims' Law, allows Colombians affected by conflict the right to apply for compensation.

Gustavo Quintero Ardila, head of the victims, peace, and reconciliation unit in Bogotá’s city government – the person in charge of reparations – told TNH that anyone can apply if they are a victim of conflict, from before or after the 2016 peace agreement.

Ardila said the government is considering extending the effect of the law beyond 2021 but that it currently lacks the financial support it needs. "The magnitude of efforts and aid should be much more than it is now,” he said.

According to Martha Aviña, head of communications at the victims’ unit, the law allows for immediate humanitarian assistance and has provisions for accommodation, food, and medical and psychological services. It also includes provisions for identification documents, health, education, family reunification, funeral assistance, occupational orientation, and income generation.

As of 2017, 106,833 applicants had filed for compensation, according to the Forced Migration Review.

But Julia Zulver, an Oxford University academic and expert on displacement in Colombia, told TNH that “only 12 percent of those registered… have been awarded any reparations by late 2018”.

“I feel like the government has just forgotten us.”

“There is also a feeling of powerlessness shared by many IDPs when it comes to making claims on the state," said Zulver, adding that she has heard stories of claimants travelling several hours to their nearest victims’ unit office only to be told they should return in a few months.

Aviña said that just 270 new victims are listed on the registry since the peace agreement in 2016. She said the responsibility to assist IDPs lies with various entities that make up the National System of Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims, and that establishing coherence among these different institutions remains a challenge.

Until the system becomes more effective, victims will complain of “feeling marginalised and of having a lack of agency when it comes to interactions with state institutions”, said Zulver.

Maria said she didn’t see the point in applying for compensation she was unlikely to receive. “I feel like the government has just forgotten us,” she said. “We were supposed to get help from [the government], but nobody has come here to help us.”

(*Name changed upon request of interviewee due to fears over safety.)

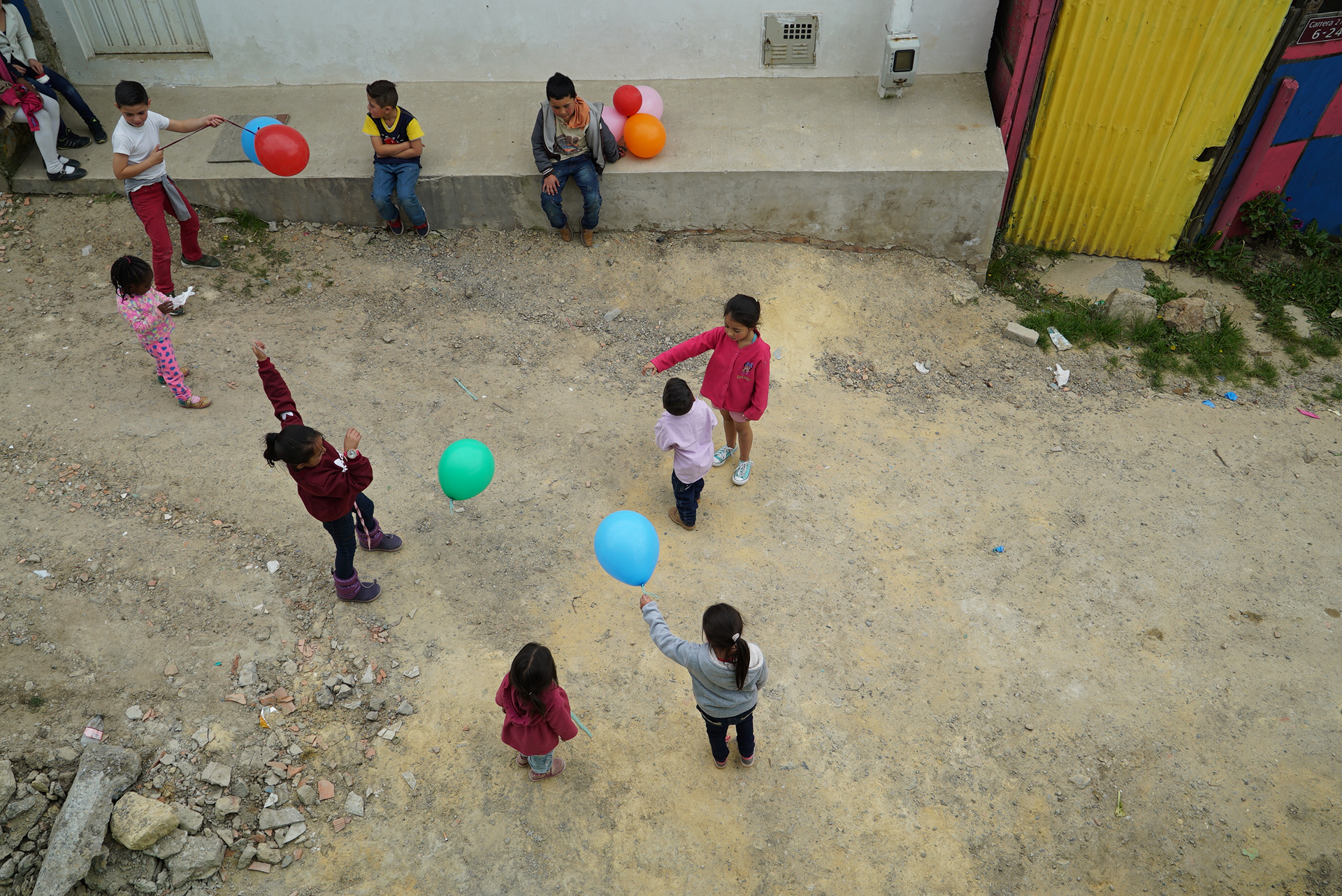

(TOP PHOTO: A small crowd of children gather in the dusty streets of Soacha Alta, waiting for Fundación Las Pulgas to open.)

ls/na/ag