At a Glance: The UN’s troubled Tripoli centre

- Faced with rising disorder, the UN’s refugee agency has decided to halt most support.

- More than 1,000 people at the unsanitary and overcrowded centre face a difficult choice: whether to stay or go.

- The UN is urging them to leave, as its flagship initiative in Libya appears close to collapse.

- Roughly 100 people have been persuaded to leave since late November.

- Backed by the UN and funded by international donors, it has cost $6 million.

The UN says it is unable to help most residents of an overcrowded refugee centre in the Libyan capital it once touted as a safe haven. To encourage people to go, it is offering money and aid, even telling them they won’t be able to register as refugees to leave the war-torn country if they remain.

Originally intended as a temporary residence for a small fraction of refugees – just those who had already been vetted by the UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR) and were scheduled for evacuation or permanent residency in other countries — the Gathering and Departure Facility (GDF) now has some 1,150 residents, well over its stated capacity.

Most arrived over the last eight months of clashes in Tripoli, including 900 who UNHCR says entered “informally”; some even bribed their way in. As the fighting has intensified, numbers in the centre have risen and many of the people inside are hoping for, or demanding, a way out of the country – even though the UN says it can’t offer that to everyone.

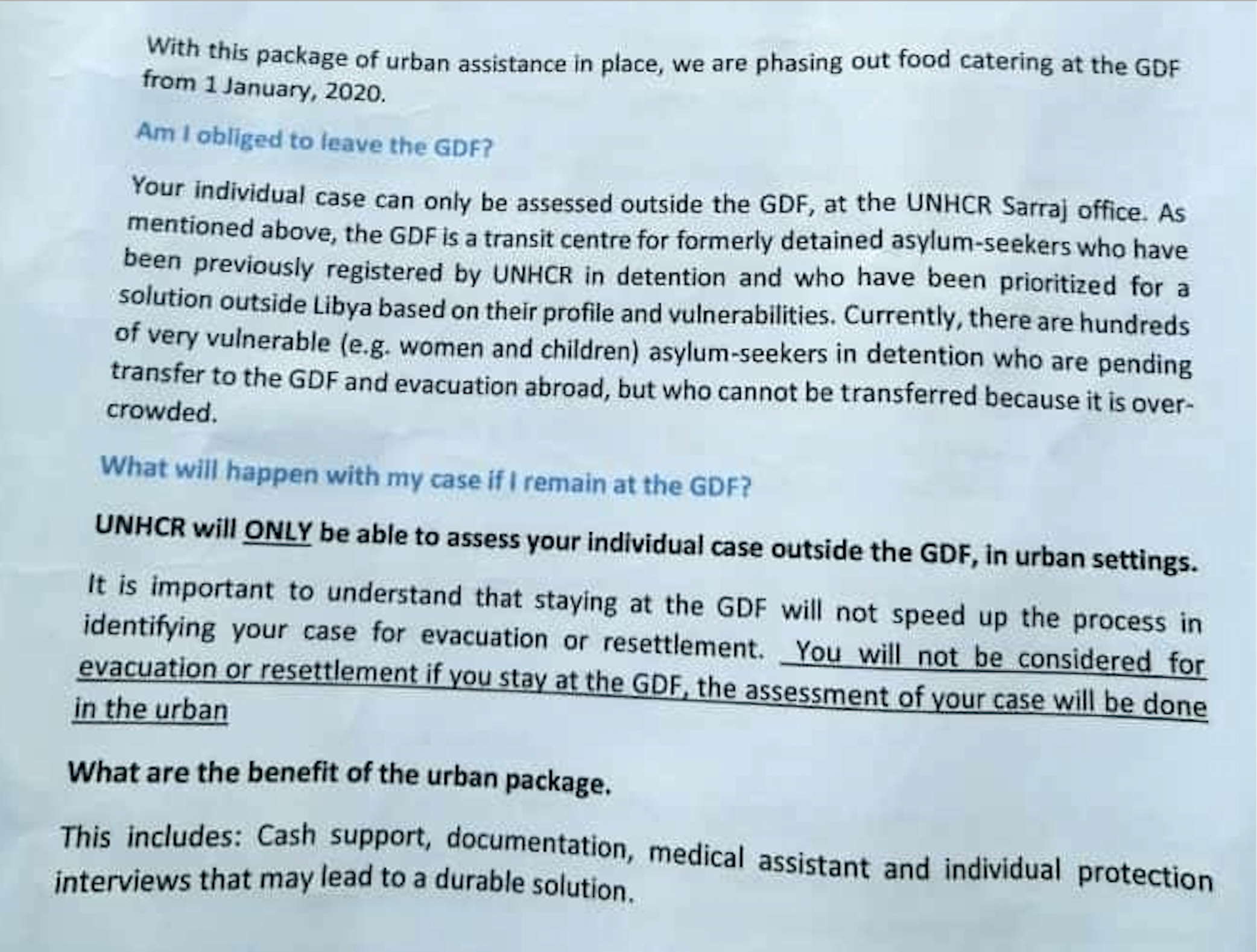

A flyer UNHCR began distributing late November at the GDF – seen by The New Humanitarian – offers food, cash, primary healthcare, and medical referrals to those willing to leave.

“You will not be considered for evacuation or resettlement if you stay,” stresses the flyer – the latest in a series of attempts to encourage those who entered informally to leave. Aid, including cash, was also offered earlier. About 100 people have taken up the offer since late November, but others have also likely entered the facility.

A source within UNHCR Libya, who requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue, criticised the effort to push people out, calling it tantamount to “blackmail” to promise them help if they go and threaten their ability to secure refugee status if they do not.

“Asylum seekers are asylum seekers and can't be denied the right to seek asylum on the basis of their stay at the GDF,” they said, adding that the aid on offer had not included “any future consideration for their protection needs or safety” once they leave.

The agency has defended its actions.

UNHCR’s Special Envoy for the Central Mediterranean Situation Vincent Cochetel pointed out that there are only two locations in Libya, both in the Tripoli area, where people can officially register their claim as a refugee with UNHCR, and the GDF is not one of them.

Cochetel said the agency can no longer provide for or protect the people inside, given that it has become overcrowded and dangerous.

“We believe the urban environment is safer for them, as long as they have a roof over their heads,” he said, adding that his agency provides various services in Tripoli, where the vast majority of migrants already live and rent accomodations.

UNHCR “is not in charge of the GDF”, and never was, according to a spokesperson, who said that the centre was under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior, which allows UNHCR and a local NGO, LibAid, to provide services there – like healthcare and food.

But it was the refugee agency that proposed the project, and a statement released after the GDF’s opening late last year said the facility is “managed by the Libyan Ministry of Interior, UNHCR, and UNHCR’s partner LibAid.”

According to internal UN documents and several sources, the $6 million facility – paid for by international donors – has now become unsanitary and is in disarray.

Many of those inside are unsure whether to stay or go.

“UNHCR is putting a lot of pressure on us to leave the GDF,” one young Yemeni man who said he was in the centre told TNH by WhatsApp. “Should I leave the GDF no matter how dangerous the situation is for us?”

How it got this bad

There are more than 600,000 migrants in Libya, including 46,000 registered refugees and asylum seekers. Some came to work, but others aim to make their way to Europe, through a country that has become notorious for the rape, kidnap, and extortion of migrants, and for squalid detention centres run by militias and gangs.

Originally intended as a waystation for those on their way out of Libya, a UNHCR press release issued last December said the then-new GDF was a place to “bring vulnerable refugees to a safe environment while solutions including refugee resettlement, family reunification, evacuation to emergency facilities in other countries, return to a country of previous asylum, and voluntary repatriation are sought for them”.

The GDF is no longer the gleaming facility shown off in promotional videos and photos when it opened a year ago, when families posed with their packed bags, and kids smiled in a playground.

An internal UNHCR report from early November, obtained by TNH, paints a starkly different picture, as do the numerous accounts of those living inside the centre.

“Sewage water flooded days ago,” it says, adding, “the toilets in all the housing are extremely dirty… [and people] are complaining of the smell”. According to the report, some people had tuberculosis, scabies had begun to spread, and “food is stored in bad conditions”.

Some of this may be due to overcrowding, although the GDF’s capacity is not entirely clear: last December UNHCR said the facility could hold 1,000 people, but that number was adjusted in subsequent statements – in September, it was 700, and in October 600.

Numbers at the centre began to increase not long after it opened, although roughly in line with capacity until fighting broke out in Tripoli — with the internationally recognised government in Tripoli and the militias that back it on one side, and eastern forces led by general Khalifa Haftar on the other.

Thousands of people found themselves trapped in detention centres on front lines, and UNHCR began evacuations to the GDF, including some of the “most vulnerable people” who had survived a July double airstrike on a centre called Tajoura that killed 52 people.

Other people were evacuated to the GDF from other centres or flocked there themselves, from Tajoura or elsewhere – drawn by the decent living conditions (it reportedly came to be known as “hotel GDF”) or because they saw it as a first step out of the country.

UNHCR tried to reserve GDF places for people it had previously registered as having a claim to refugee status – but distinguishing between refugees and other migrants has been at the heart of why the centre ran into trouble.

In late October, hundreds of residents from a separate Tripoli detention centre called Abu Salim managed to leave, and they too headed for the GDF, even though UNHCR described the facility as “severely overcrowded” at the time.

The guards who surround the GDF eventually let them in. Several sources, including UNHCR’s Cochetel told TNH that the guards — provided by the Tripoli government’s Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM) — took bribes to do so.

Unrealistic hopes?

Libya is not a party to the international refugee conventions and does not accept refugees itself.

That leaves those who have not made it out of Libya and to Europe with limited options.

The UN’s migration agency, IOM, coordinates “voluntary humanitarian return” for migrants who want to go back to their home countries: nearly 9,000 people have opted for this option in 2019.

UNHCR, meanwhile, registers asylum seekers and refugees in Libya for possible moves to other countries, including permanent resettlement (774 people this year), or evacuation to countries who have agreed to take them, but not as citizens, like Rwanda (1,410 in 2019).

Until recently, UNHCR said the Libyan authorities had only allowed it to register people from nine countries for refugee status, but Cochetel said this had now changed and the agency could take the details of people of any nationality.

In addition to cash and healthcare, UNHCR says people who leave the GDF are eligible for “documentation,” and a spokesperson said “there is a commitment from the authorities not to detain asylum seekers holding UNHCR documents.”

But, even after registration, these papers do not confer the right to work, nor do they guarantee safety: Libya is a divided country with multiple authorities, none of which are party to refugee conventions and officially recognise UNHCR documents.

Kasper Engborg, deputy head of office for OCHA Libya, the UN body that coordinates emergency response, explained how those flocking to the GDF often have expectations that go beyond just shelter.

“They all went there in the hopes that this could be the first gateway to Europe, and they have obviously left [their home countries] for a reason. We are not in a place where we can judge what reasons people left for.

“They believe as soon as they are in the GDF they are halfway on their way to Europe,” Engborg said, pointing out that not many countries have so far stepped up to offer spots to people who claim asylum in Libya, many of whom come from sub-Saharan Africa.

A UNHCR report says 6,169 resettlement places have been found since September 2017, and over 4,000 of those have already been allocated.

“At the end of the day it is the countries who decide who they want to take and how many people,” Engborg said.

UNHCR’s Cochetel put it differently: “[Many] people believe UNHCR is a travel agency and we should resettle them all.” With limited spots available, he asked, “how do we do that?”

While much of the blame for the current chaos in the GDF appears to have been placed on the new influx of people and a lack of resettlement spaces, others say the current situation points to problems that were there from the start.

The GDF is across the street from the headquarters of the DCIM and a detention centre it runs, allowing people to slip between the facilities.

That means, according to multiple sources who work in Libya’s aid operation, all of whom requested anonymity, that physical and administrative control has largely been dictated by local authorities, and occasionally the militias that back them and provide armed security.

UNHCR’s Cochetel said the agency had limited choice in who it would work with in the GDF, and which firms to contract for services.

It’s “costing us enormous amounts of money; we cannot choose the partners”, he said. “We pay for food four times the level we should be paying.”

Two sources, both of whom requested anonymity, said part of the problem at the GDF stems from the fact that UNHCR never had a clear-cut agreement with the Libyan authorities – who are themselves split – on how the agency and its local partner, Libaid, would be able to operate inside the facility.

What’s next?

As controversy for the centre continues to swirl, it’s not clear what’s next for the GDF, and more importantly, for the people inside.

A UNHCR spokesperson said a catering contract that provides hot meals to the people who entered the centre without vetting will end at the start of next year, but the UN denies it will let GDF residents go hungry. It says, too, that it will not shut off the electricity or stop providing aid altogether.

“People are not going to be left in a starving situation,” said Engborg. “[If people do not leave] then other solutions will be found.”

But those solutions – one floated by a UNHCR spokesperson includes the possibility that the facility could “be run as an open centre, administered by the Libyan government, where different UN agencies and partners could provide various services” – would have to be approved by the authorities in Tripoli.

If conditions don’t improve, the UN could pull out altogether.

The spokesperson said that “for the UN to remain engaged, the centre would need to be a purely civilian facility where agencies and residents would have unhindered access and freedom of movement”.

One DCIM source, who requested anonymity because they were not authorised to speak to the media, said Tripoli authorities were unlikely to allow an unguarded centre on their doorstep.

So far, there is little sign of others stepping in. Several international groups involved in providing aid to migrants and refugees declined to speak on the record about the GDF or say if they would pitch in to help those currently there.

In the meantime, emotions are running high inside the centre, as desperate texts sent out to various media outlets lay bare.

“It is a very confusing situation, and it is also a very difficult situation, because you are dealing with people’s hopes and emotions,” Engborg said. “Therefore, whatever rational decision that we often need to take, we are up against people’s legitimate hopes and emotions.”

Leaving the GDF may mean a registration appointment, cash, and other help. But for some, staying may keep some semblance of safety and the dream of a new life elsewhere alive.

Only around 100 residents have taken the UN up on its offer since it began distributing flyers, according to an aid worker in the centre. But the UN’s attempts to coax people out of the GDF and dissuade others from entering have largely proven unsuccessful. And, with no agreed resolution, it might get worse still.

While “some people are leaving… new people are coming in”, said Cochetel. “They bribe, pay their way in… I have the feeling that more people will go there, thinking they will get better assistance at the GDF. [But] it’s not true.”

Additional reporting by Ben Parker.

sc-as-bp/ag