Venezuelans have taken to the streets in their tens of thousands over the past seven weeks in anti-government protests that have left at least 43 demonstrators dead and hundreds injured. They show no signs of abating.

But lurking behind the political protests is a deepening humanitarian crisis that gets less press: Malnutrition has risen sharply, maternal mortality jumped by 65 percent last year, infant mortality by 30 percent. The protests are just the tip of a much more alarming iceberg. The truth is that many of the worst-off Venezuelans are too poor and too hungry to protest, even if they wanted to.

Over the past two years, falling oil prices have sent Venezuela’s economy into freefall. The result: chronic shortages of food and medicines, rampant crime, and an inflation rate estimated to be 720 percent and rising.

The anger on the streets is prompted in part by the denial of President Nicolás Maduro’s socialist government that there is a crisis (the health minister was sacked shortly after her department released the infant and maternal mortality figures) and its refusal to allow in international aid.

While the protest movement has been led by the predominantly middle-class opposition, those suffering the most from the food shortages and lack of functioning health services are the poorest households that once backed former President Hugo Chavez. While many no longer support the government, they feel little affinity with the opposition and are often too preoccupied by the daily search for food to join the protests. Their individual stories reveal as much about Venezuela’s crisis as the near daily scenes of protesters clashing with riot police.

Forced to choose: diapers or medicines

Barbara Mendez marks the end of each day in her mental calendar as another day that ‘Nely’, her eight-month-old daughter, has survived. Nelysmar was born with a heart condition resulting from a blood vessel that failed to close after birth. Blood now moves erratically between her heart and lungs.

“It is a miracle that she is still alive,” says Bárbara, who is only 16 but has the care-worn face of someone much older.

There is no treatment for Nelysmar’s condition. The only solution is a surgical procedure for which she has been on a waiting list since the day she was born. At the Children’s Cardiology Hospital in Caracas – the only hospital in the country that performs such procedures – less than half the operating rooms are functioning, due to a lack of maintenance. Nationally, less than 10 percent of operating rooms are fully operational and 40,000 people are now on waiting lists for surgery, according to the Venezuelan Health Observatory (OVS).

Nely’s condition often leads to infections that require antibiotics, a major expenditure for Bárbara, who dropped out of high school to care for her daughter and now relies on her boyfriend’s parents for support.

According to the Venezuelan Federation of Pharmacies, around 85 percent of medicines are unavailable here. People are forced to travel to neighbouring countries to find the medicines they need. Those that can be found within the country are often sold on the black market at prices unaffordable for people like Bárbara.

At a certain point, she had to choose between buying diapers or medicines. She chose medicines and substitutes rags for diapers. As a result, Nely suffers from painful rashes.

Bárbara and Nely have spent countless sleepless nights at the hospital because of Nely’s respiratory problems. Bárbara listens terrified as Nely gasps for breath.

“I'm well aware that she can die at any moment,” she says. “I'm praying every day for that call from the hospital.”

Teachers and pupils go hungry

Vanessa Posada, 36, grew up in what she describes as an average, middle-class family in Caracas. She went to university and then found a job as a school-teacher, before getting married and having a child. “Everything was on the right track. I was happy,” she says.

Then Venezuela’s economic crisis hit her family. Starting in 2014, the cost of food began to rise much more rapidly than the wages earnt by Vanessa and her husband, Adolfo. They sold their car and were forced to move into the house they had been building but couldn’t afford to finish.

Last year, Vanessa had an accident that damaged her right knee and kept her at home for four months. She was fired from her morning teaching job and left with only a few hours of teaching at another school in the afternoon. Her and Adolfo’s salaries combined had been just enough to buy food. Now, there wasn’t enough money even for that. First, the family eliminated meat from their diet; then they subsisted on rice and beans. Now, many evenings, the couple eat only one plantain or skip a meal to ensure their six-year-old son, Armando, can eat.

Vanessa has lost more than 10 kilos in less than a year and only weighs 46 kilos. According to an annual survey of living conditions in Venezuela conducted by three universities (ENCOVI), three out of every four Venezuelans lost an average of 8.7 kilos last year. The same study found that 93 percent of Venezuelans have insufficient money to buy food.

At the school where Vanessa works in the afternoon, the situation is no better than at home. Students are increasingly skipping school because they are too weak from lack of food. An estimated one million Venezuelan children are now out of school and classes are regularly cancelled due to teachers being absent.

A few weeks ago, one of Vanessa’s students stole her classmate’s lunch because she was hungry. Now, Vanessa shares her lunch with the girl.

“They’re like my children; I can't let them starve, no matter how hungry I might be.”

Extrajudicial killings

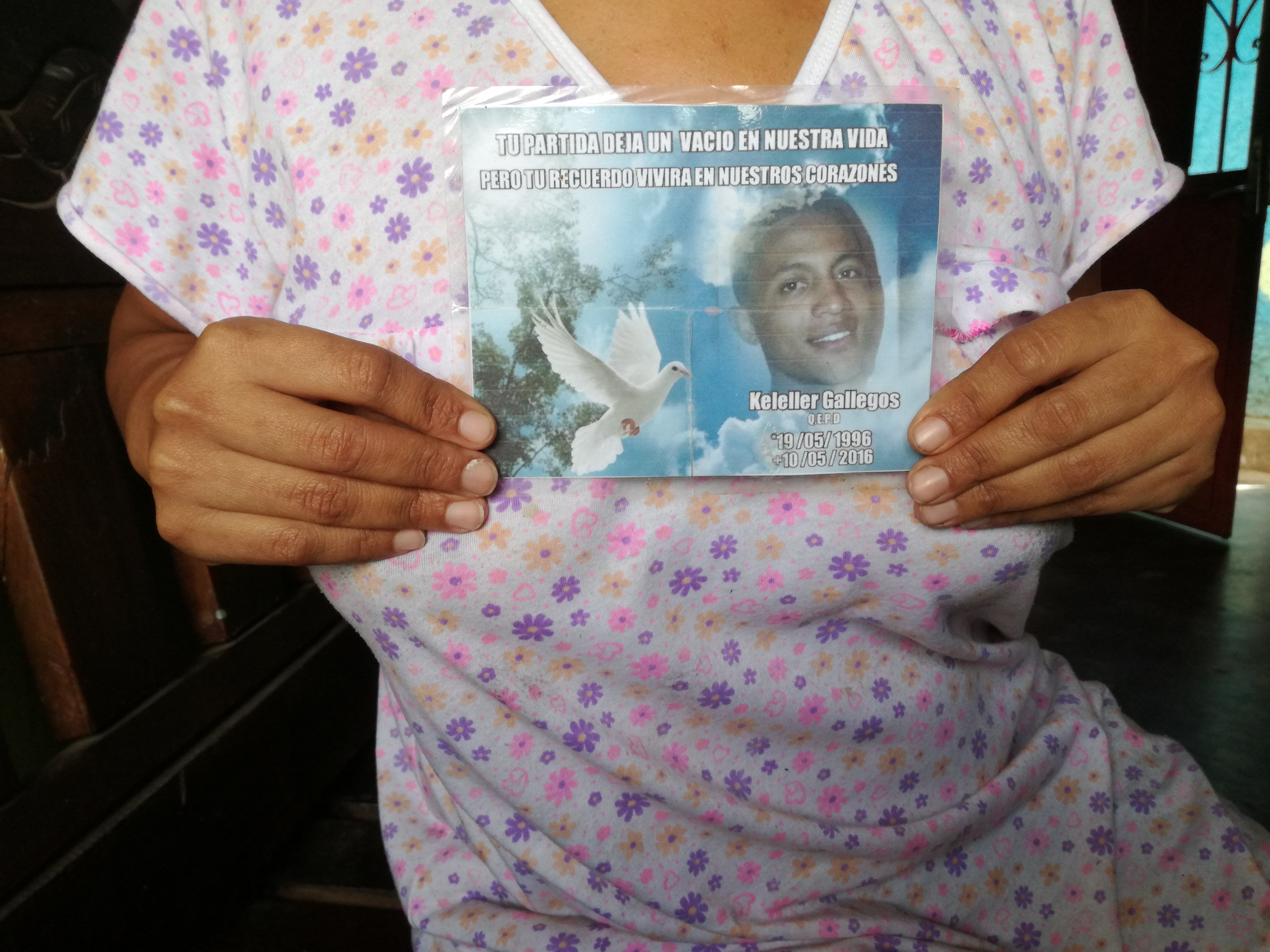

His name was Keleller Gallegos Reverte and he died one morning last May when a group of 12 soldiers burst into his house and shot him as he woke up next to his wife. He was 19.

The raid on Keleller’s house was part of an anti-crime offensive called OLP (Operation Liberation and Protection of the People), which launched in 2015 with the goal of reclaiming neighbourhoods controlled by criminal gangs. Critics of the initiative say it has spread more violence and fear in the country and has been responsible for grave human rights violations.

Keleller was innocent, says his mother, Natalie Gallegos, who suspects the soldiers were looking for her brother, Luis Carlos Reverte, aka El Coqui, a well-known criminal in the area who has been dodging the authorities for more than 10 years. “Nobody picks their family,” says Natalie with a sigh.

Venezuela’s crime rates have been climbing in recent years, as the financial crisis has deepened. They are now among the highest in the world. The Venezuelan Observatory for Violence estimates there were 28,479 violent deaths in 2016, including 5,281 classified as resulting from “resistance to authority”.

The security forces’ heavy-handed response to crime has been blamed for decimating Venezuela’s poorest neighbourhoods. Local human rights group Proveo claims the OLP was responsible for the extrajudicial killings of more than 700 people between July 2015 and September 2016. Many of the victims were innocent young men with no criminal records like Keleller. According to Natalie, after killing her son, the soldiers fired bullets all over the room to make it look like the scene of a confrontation.

A year after his death, the complaint she lodged with the Attorney General's office has gone unanswered. Amnesty International has noted that only three percent of complaints relating to the OLP result in the culprits facing criminal charges.

“In this country, there's no justice,” says Natalie.

[TOP PHOTO: A tearful woman shaking a bag of flour was among hundreds of people who'd been waiting in line for hours outside a supermarket in western Caracas, only to be told there was no food left for them to buy. Meridith Kohut/IRIN]

mz/ks/ag