In a small room in Kampala, over cups of coffee and quiet conversation, Sudanese refugee women gather to speak about what they have endured. War, displacement, and loss hang in the air – but so does something else: relief at having a safe space to speak.

These gatherings are part of Funjan Niswan, a grassroots initiative run by Aminat, a women-led organisation that offers psychological support to Sudanese refugees in the Ugandan capital.

I have encountered many such initiatives since escaping the war in Sudan and living in South Sudan, Uganda, and now Rwanda – a testament to the organising power and resilience of the Sudanese people. But as a photographer, I was especially drawn to this one.

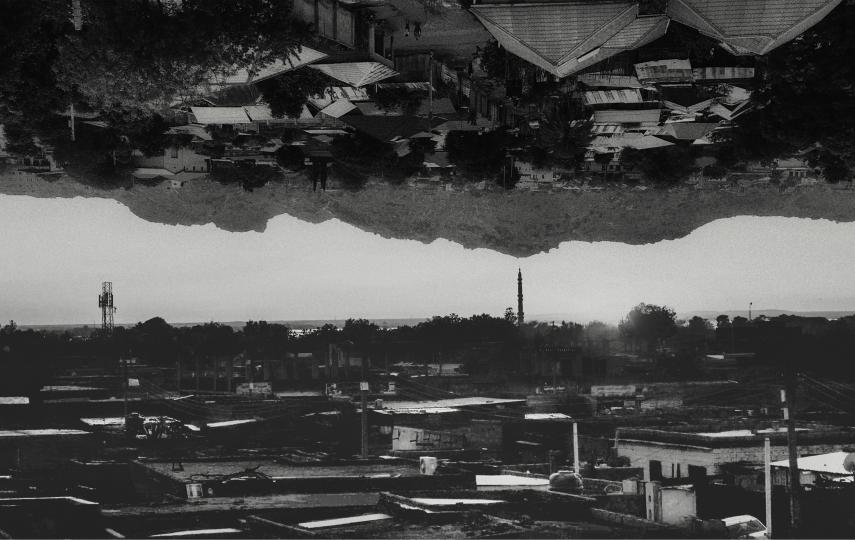

Born out of the war – which began in April 2023 and has created the world’s largest humanitarian crisis – Aminat was founded by a group of women, many from activist and civil society backgrounds. They met at a workshop in Kampala and decided to build something practical for Sudanese people in exile.

What stood out to me was their use of traditional coffee gatherings as the foundation for their sessions – informal, warm, and closer to friendly conversations than formal therapy. It reminded me of my mother’s weekly coffee meetings in our neighbourhood in Omdurman, a city adjacent to Khartoum.

For dozens of women carrying unprocessed trauma, I saw how these sessions became a lifeline. And after meeting the organisers and witnessing their work, I also realised that the healing goes both ways: The space nurtures the women who come to speak, but also those who facilitate the sessions.

As a refugee who also struggles with mental health issues, I wanted to share this story because it shows how powerful community-led spaces can be – and how healing doesn’t always have to look clinical or formal. Sometimes, it starts with coffee, conversation, and the simple act of being heard.

With the war in Sudan showing no signs of easing, and an estimated 11.5 million people now displaced – including more than four million who have fled to neighbouring countries – initiatives like Aminat are only becoming more vital.

Scroll through the photos and text below to meet the women behind the initiative and some of those who have found support through its sessions.

“Reaching people in their homes helps them become comfortable.”

Mona Gasim is one of the founders of Aminat. She studied medical engineering at a university in Sudan but was unable to work in the field after facing discrimination because of a disability. Instead, she turned to civil society, volunteering and leading awareness campaigns focused on the rights of disabled people.

Mona told me that Aminat began with 20 founding women as a broad campaign to educate Sudanese refugees about their legal rights and responsibilities, while also offering psychological support through Funjan Niswan, which roughly translates from Arabic as “women’s cup of coffee”.

What started as a multi-purpose initiative soon revealed a deeper need, and psychological support became central to the group’s work. Many participants – as well as the founders and facilitators themselves – were carrying unprocessed trauma they had not had the chance to address.

Funjan Niswan sessions are located in participants’ homes in different neighbourhoods of Kampala. “Reaching people in their homes, where they feel safe, helps them become comfortable enough to speak and open up,” Mona said.

In addition to the coffee sessions, she said Aminat runs an emergency psychological support room. When necessary, participants are connected with a psychologist. If further care is needed, they are referred to a psychiatrist to explore treatment options.

Mona said she has become one of Aminat’s core members because she feels a responsibility to represent people with disabilities, whose concerns she believes are too often overlooked. She is also committed to making the sessions as inclusive and representative as possible.

“As Sudanese, we love to live together within our communities and among people who look, talk, and share the same habits and heritage,” she said, explaining the importance of diversity.

“The war in Sudan has shown us how strong Sudanese women truly are.”

Nusaiba is another member of Aminat. She told me that Funjan Niswan has opened her eyes to aspects of Sudanese women’s experiences she had never known before. Through the sessions, she has learned stories of hurt, resilience, and strength.

“The war in Sudan has shown us how strong Sudanese women truly are,” she said.

For Nusaiba, the sessions are not only for participants; the facilitators also share their experiences and seek support. She believes trust is the foundation of the space, and she builds it by opening up about her own life. By sharing personal stories and vulnerabilities, she shows that she, too, has faced hardship, encouraging others to speak freely about their emotions and experiences.

She said she knew the approach was working when participants began talking openly, without needing prompts or invitations – the room simply became a place where stories could surface on their own.

“The more you talk, the more you lose a burden from your chest”

Tayseer Salih had mixed feelings about seeking support until one day she was invited to an Aminat workshop by her longtime friend from civil society, Mona Gasim (profiled above).

Tayseer said she found the session valuable. Hearing other women speak helped her realise that many had lived through struggles similar to her own and yet they were still finding ways to move forward and heal.

“The more you talk, the more you lose a burden from your chest,” she told me. “Lately, I haven’t been talking much, and I haven’t liked it. But through these sessions, I heard others telling their stories, and I felt they were similar to my own — even if I didn’t share mine.”

Tayseer believes psychological support requires more time than a two-hour talking and sharing session. “What we have been through is too big to be discussed in only a few hours,” she said. “Psychological expression needs more time.”

An agriculture and gardening expert, Tayseer has long been involved in promoting peace and human rights. After the war broke out, she moved from Khartoum to Al Gadaref, in eastern Sudan, where she co-founded an initiative supporting women and children. She also volunteered with a local emergency response room and organised peacebuilding workshops in her neighbourhood.

But authorities banned the workshops, and her activism drew harassment and threats. The emergency response room was shut down, and when she opened a kitchen to feed displaced people, she was falsely accused of receiving money from the Rapid Support Forces – the paramilitary-turned-rebel militia battling the Sudanese army.

Now in Kampala, Tayseer lives alone and has been deeply affected by exile.

“Since I arrived in Uganda, I haven’t been able to think properly, or work, or do anything. Nothing helped me return to a normal life. I don’t feel I’m living regularly. I was never someone who stayed at home — now I can sit in my room for 10 days without leaving.”

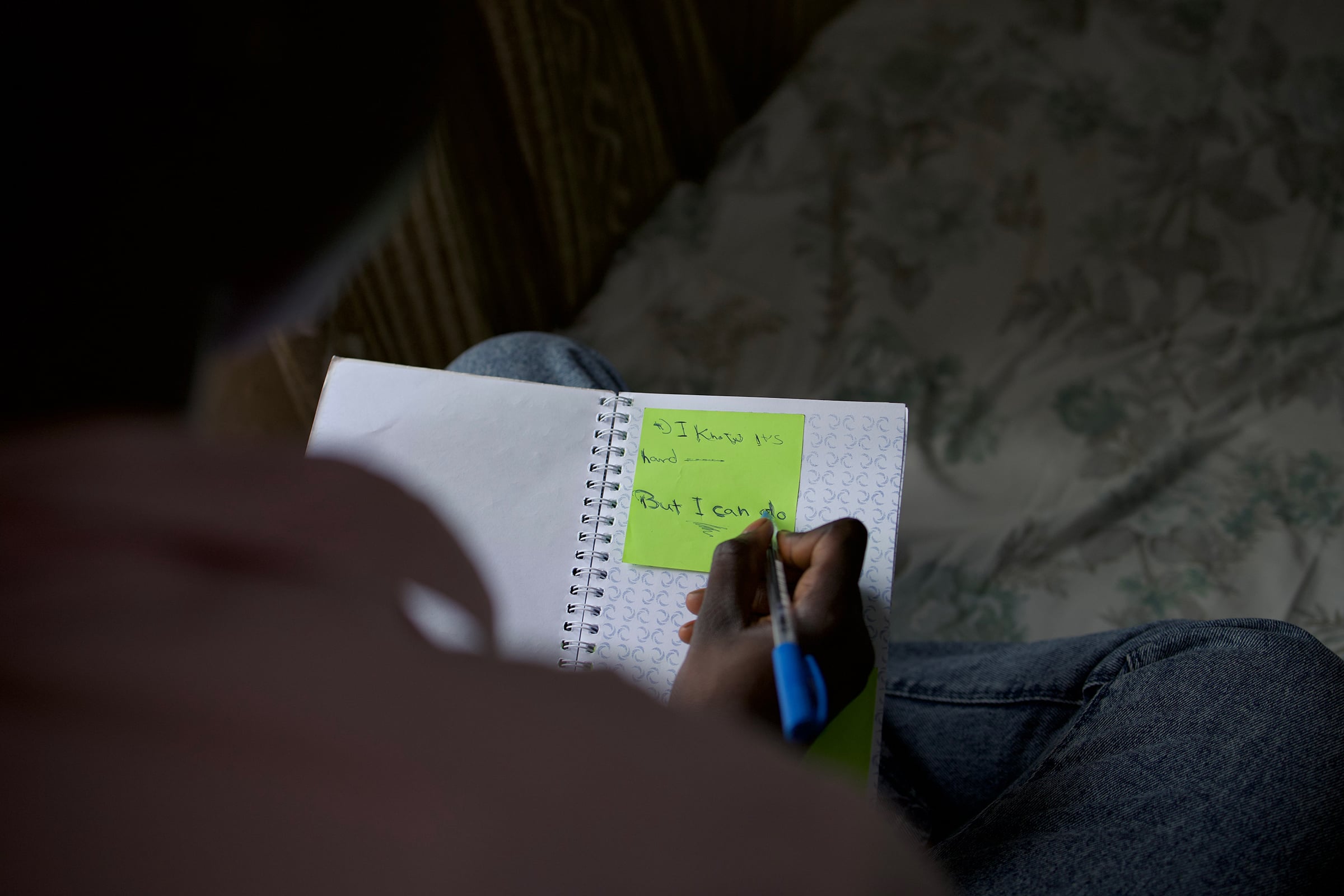

To manage stress, Tayseer said she often turns to sport. She keeps small mementos, like stickers collected after sharing ice cream with a friend. Creative practices such as bead-making and crochet also help her cope, making life feel more bearable. Some old habits, however, have become difficult to return to.

“I was a person who loved reading,” she said. “But I haven’t read a single book since this conflict began.” Even prayer, she added, has sometimes felt heavy.

“Women in exile are under more pressure than ever”

Rayan Nabil, 20, is another participant in the Funjan Niswan sessions. Originally from Omdurman – where she studied and volunteered with homeless children – she now works at a feminist centre called Their Voices in Kampala.

Her connection with Aminat began last year, after a friend introduced her to the initiative. Rayan was immediately struck by the way her friend spoke about it – with admiration, trust, and deep belief in the group’s work. She was later invited to attend a Funjan Niswan session, and although she could not stay for the full gathering, even that brief experience left its mark.

After the session, Rayan felt emotionally drained by the stories she heard and the amount of collective grief in the room. But the following day, she felt an unexpected sense of relief – as if a heavy weight had been lifted and negative energy released.

Aminat’s members continued to check in with her and other participants, she said, both privately and through a WhatsApp group, offering steady support that became crucial to her healing.

“Usually, I couldn’t express myself even to my friends because I felt they would judge me,” she said. “But I didn’t feel that at all in the sessions with Aminat.”

Rayan said writing in her notebook has become another important way of coping. Sometimes she records her feelings; other times she writes encouraging phrases to lift her spirits. Being separated from her extended family has left her feeling lonely and, as someone who values family deeply, she believes there needs to be greater awareness around emotional expression and mental health.

“Women in exile are under more pressure than ever,” she said. “That’s why they need to pay attention to their mental health – so they can take care of their families too.”

Rayan fled Khartoum after the war erupted on a perilous journey marked by threats from thieves and a frightening encounter at a military checkpoint. After reaching Al Gadaref, she fell seriously ill with dengue fever before continuing to Port Sudan, where she struggled to find shelter until a family took her in. When she arrived in Kampala, she spent months largely confined indoors before beginning the refugee registration process in a camp, where overcrowding, corruption, and harsh conditions left her sleeping on the ground.

She also carries deep trauma from threats made against her by unknown individuals after her mother publicly criticised both the RSF and state security online. Individuals warned they would rape Rayan to punish her mother – messages she discovered by accident, leaving her terrified and unable to sleep.

Cases like Rayan’s underline why initiatives such as Funjan Niswan are so vital. Organisers say the group has reached nearly 100 participants so far – a significant impact for a small volunteer-led initiative. Yet the needs among Sudanese women in exile remain vast, far outstripping the resources available to respond.