The Colombian border town of Cúcuta is the main point of exodus for Venezuelans leaving their troubled homeland, with up to 40,000 people crossing backwards and forwards here each day.

Most arrive with hopes of new lives and new opportunities in Colombia, while others aim to travel, often by foot, on to other South American countries like Ecuador and Peru. Somewhere between three and four million Venezuelans have left since 2015.

Read more: International politics and humanitarian aid collide in Venezuela

Journalist Steven Grattan went to Cúcuta, once a thriving hub for Venezuelan tourists, and discovered how it is struggling to host hundreds of thousands of new migrants who have landed in a region where education and health institutions are now at breaking point.

Harsh realities greet many new arrivals, as their journeys and dreams of a fresh start become derailed by their own lack of resources and by the shortage of opportunities they find in Colombia.

Day-trippers

Some Venezuelans cross into Colombia simply to buy basic food and supplies to take back to Venezuela. They bring suitcases, like the man in this photo heading back along the Simón Bolívar border bridge – the main point of entry between the two countries. Flour, eggs, toilet roll, and toothpaste are hard to come by, or are extremely expensive. Many are now scared to migrate, knowing that Colombia and other nearby countries are saturated with their fellow citizens, as jobs and opportunities abroad have dried up.

Colombian refugees returning

As recently as a decade ago Venezuela was one of the richest countries in the region, playing host itself to more than a quarter of a million Colombians fleeing war and persecution during the armed conflict between Colombian government forces and leftist FARC rebels. Freddy Garzon, 49, was one of those whose family fled Colombia and moved to Venezuela, in 1974. He is now fleeing the other way with his children, aged seven and nine. “I can’t imagine going back [to Venezuela] again. It’s really affected my head,” he says.

Hunger

This is the priority line for parents with young children outside a church-run soup kitchen in Cúcuta. Some 7,500 meals are provided here six days a week, Monday to Saturday. There is a line for the elderly too. Many depend on these meals to help them through the first steps of their migration into Colombia. However, many Venezuelans who live near the border also cross daily and queue for rations as food on the other side is so scarce.

The cooks

Cooking plantain for 4,000 people’s lunch is no easy task. Elvis Baracho (at the front), 25, is a Venezuelan migrant who has worked at the soup kitchen for almost two years. His salary is minimal ($26 a month), but it allows him to pay for basic needs and he gets two free meals a day. Angel Jose, 25, (behind) lives in a tin house on the outskirts of Cúcuta with his wife and disabled child. In addition to his work at the soup kitchen, he cuts hair. He charges 2,000 pesos (63 cents) per cut, half of which goes to the woman who rents him the clippers.

Twelve to a room

Since migrating to Colombia six months ago, Lesther Lopez, 42, has been selling her Aloe Vera concoction around Cúcuta. It supposedly helps with liver, kidney, and cholesterol problems. She says that coming to the soup kitchen for lunch each day means the little money she earns can go toward paying the $95 in monthly rent she is charged for the one room she shares in Cúcuta with 11 others, including her children aged 22, 19, and 14.

Scraping by to send money home

Jesus Betancurt sits on the pavement in the sweltering heat on the Simón Bolívar bridge selling biscuits and sweets to passersby. He crossed over a week ago in search of a job. “I live with the hope of being able to send something back to my family,” says the 48-year-old from Carabobo State. “I’ve been trying to find work, but this is all I can get for now.”

Moving on

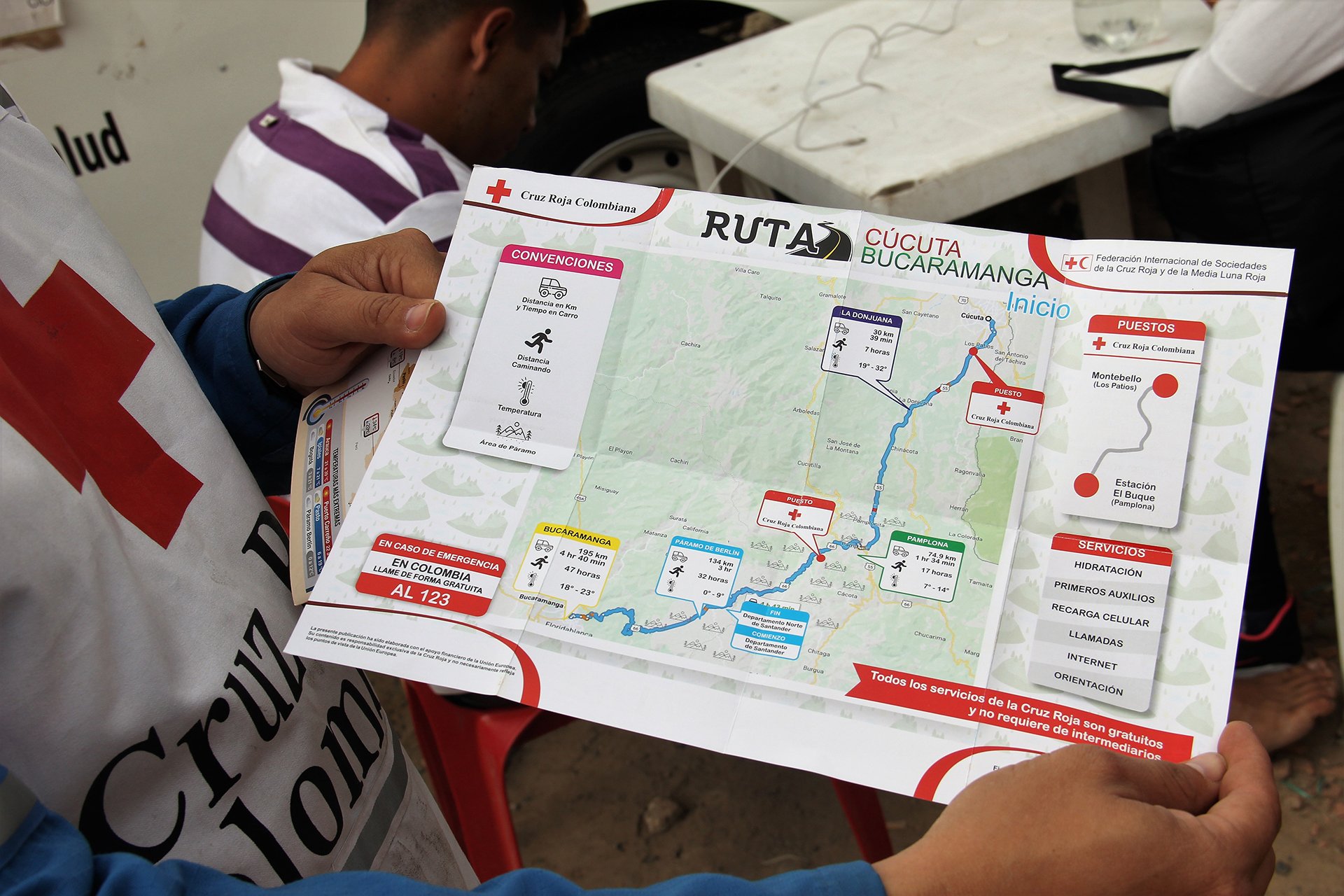

This map is given by the Red Cross to Venezuelan migrants walking into Colombia. It shows a 47-hour walk to the city of Bucaramanga, a small fraction of the route many will take on to Ecuador or Peru. The road winds high into hills, and people often have to sleep rough in cold nighttime temperatures.

Hitching a ride

For those leaving Cúcuta, the first stop is the hilltop town Pamplona. Many come on foot on their way to Bucaramanga. In the photo above, migrants leaving Pamplona are trying to hitch a ride from a passing lorry, The migrants often travel vast distances on from here on foot, through the Colombian wetlands, many with suitcases and few resources.

Escaping the heat

Most don’t get picked up, but these migrants are lucky enough to hitch a ride on the back of an empty lorry. The heat on the road is intense, so they are happy to catch a break. Most of these migrants are trying to leave Colombia for Peru and Chile because they believe there might be more opportunities for work in those countries. Others are searching for family members who have gone before.

...

For more on the situation within Venezuela, read our in-depth reporting: A humanitarian crisis denied.

(TOP PHOTO: Sergio Carmargo, 59, in the elderly line at the church-run soup kitchen in Cúcuta. CREDIT: Steven Grattan/IRIN)

sg/wp/ag