#BlackLivesMatter and the COVID-19 pandemic are exposing the hypocrisies and structural problems that have long underpinned international humanitarian action, said activists, aid workers, and analysts during an online conversation recently hosted by The New Humanitarian.

In a departure from the diplomatic parlance that tends to dominate discussions about reform of humanitarian aid, they called for taking a “sledgehammer” to systems that perpetuate inequality, de-funding institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and abandoning the humanitarian principle of neutrality as ways of “decolonising” international aid.

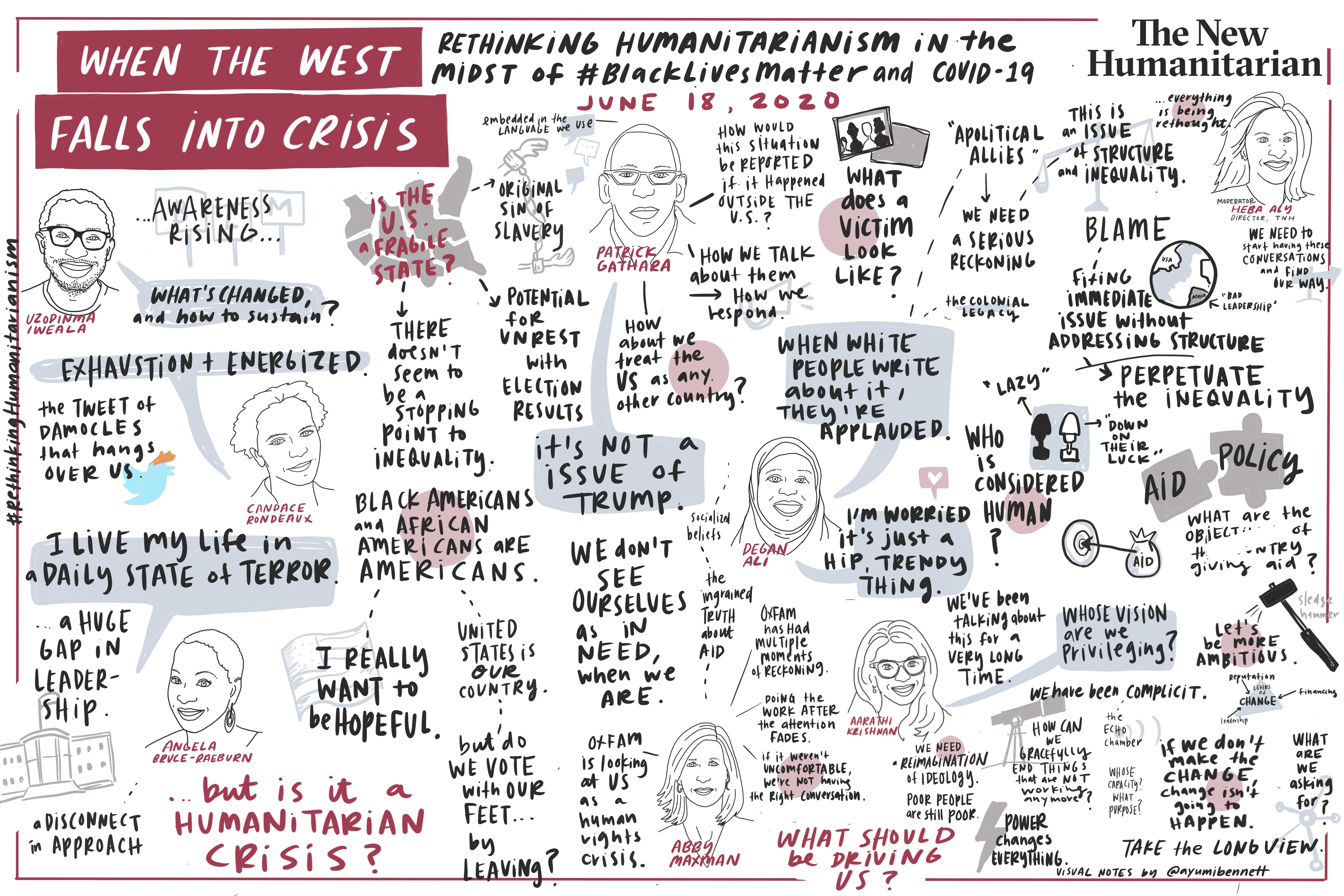

As police brutality in the United States and soaring coronavirus deaths in developed countries challenge assumptions of who is ‘in need’, TNH Director Heba Aly sat down with seven thinkers to explore how this historic moment is changing our definition of crisis; whether the traditional conceptions of humanitarian aid are still relevant; and alternative visions for international solidarity moving forward.

Here’s what they had to say during the discussion, titled When the West falls into crisis: Rethinking humanitarianism in the midst of #BlackLivesMatter and COVID-19.

• Candace Rondeaux, who spent years as an analyst with the International Crisis Group before joining the Center on the Future of War and New America’s International Security Program as senior fellow

• Uzodinma Iweala, award-winning writer and filmmaker and CEO of The Africa Center

• Angela Bruce-Raeburn, aid worker and regional advocacy director for Africa at the Global Health Advocacy Incubator and member of Black Women in Development

• Abby Maxman, CEO of Oxfam America

• Patrick Gathara, cartoonist and political commentator

• Degan Ali, CEO of Adeso

• Aarathi Krishnan, humanitarian foresight advisor

American exceptionalism: ignoring problems at home

How can humanitarian organisations justify deploying to programs overseas while ignoring the myriad inequalities and injustices in their own backyards?

Angela Bruce-Raeburn, regional advocacy director for Africa at the Global Health Advocacy Incubator in Washington D.C, and member of Black Women in Development, recalled the disillusion she felt while working at Oxfam America.

It was 2015. The death of another unarmed black man, Freddie Gray, while in police custody had sparked riots in Baltimore. While responding to instability in Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bruce-Raeburn and her colleagues “had no conversation that there were black people in [Baltimore] getting tear gas and rubber bullets shot at them.”

Is the US a humanitarian crisis?

Following a crackdown on peaceful protesters and targeted attacks on journalists in the US, international monitoring groups, including the International Crisis Group, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, and the Center for Civilians in Conflict, condemned excessive shows of force and threats of domestic military employment in America.

“The US is an increasingly fragile state,” said Candace Rondeaux, who spent years as an analyst with the International Crisis Group before joining both the Center on the Future of War and New America’s International Security Program as a senior fellow. “The risk of [state] failure is highly dependent on how American citizens, as well as leaders, rise to the occasion that we're about to face in this pre-election and post-election period.” The good governance the US seeks to promote abroad, including free elections, democracy, and a representative government, could now be at risk of failing at home, she added.

The possibility of a failed US state and direct threats against Black Americans could see them seeking to flee elsewhere, said Uzodinma Iweala, CEO of The Africa Center in New York, and author of Beasts of No Nation. “What do you do in a state that is unable or unwilling to protect or realise your rights?” he asked.

The pandemic has further exposed the changing face of vulnerability, and some aid organisations have started to expand their focus to Western states. For instance, Doctors Without Borders has opened programs in Canada, Italy, Switzerland, and the US.

“We have had multiple moments of reckoning, and this is another one of them,” said Abby Maxman, president and CEO of Oxfam America. “We are looking at [the situation in the US] as a human rights [and] humanitarian crisis,” she said, noting that Oxfam is currently working in nine American states, including North Carolina, Mississippi, and Massachusetts, on a “social justice humanitarian agenda” in response to COVID-19.

Narratives of need

The fact that the US may not see itself as a country in need is a result of industry narratives that have labelled certain countries and people as the receivers of aid, panelists said.

“The way we talk about crises determines how we will respond to them, how we understand them,” said Kenyan cartoonist and political commentator Patrick Gathara. While certain countries have become the “home” of humanitarian situations, places like the US continue to be classified as exceptional.

But what if the tables were turned?

“Can we imagine the deployment of an African peacekeeping force to the US?” asked Gathara. The international community’s resistance to imagining such a change in roles demonstrates how entrenched the assumption is that humanitarian crises are “far away” problems for Western countries, the panelists noted.

Bruce-Raeburn also noted that white people who are on the welfare system are described as “just down on their luck”, while when Black people are on welfare, “it's a generational pattern”. This type of white exceptionalism also found in aid reinforces the idea that poor people are in need because of bad choices or because they’re lazy, she said, and overlooks the racism, colonialism, and legacy of slavery that put them in that position in the first place.

A structured design of injustice

The importance of addressing the systemic causes of inequality – and the aid sector’s role in propping up an international system that perpetuates them – was a touch point for every panelist.

For Iweala, the liberal, capitalist world order – including international aid institutions developed in the post-World War II era that are now charged with helping the world’s poor – was built on the backs of slaves, labour that amounts to at least $16 trillion if paid at minimum wage, according to one estimate.

Aid only works, he said, if people believe “that black people will always be an underclass… It’s buying into the system if we believe that the West or the North will always be on top – that it’s money coming from ‘rich countries’ or from the developed world to the developing world…

“This whole entire ecosystem was actually built off the backs of the resources [and human labour] that were extracted or… transferred to build up some of these systems.”

Degan Ali, the CEO of Kenya-based NGO Adeso, concurred that the language used to describe crisis situations obscures the UN Security Council decisions (or lack thereof) and Western-led extractive industries that have kept so-called developing countries in debt and in crisis.

On the current interest in discussing racism in aid, she said: “I worry that it’s becoming the trendy thing. Everybody is saying that they’re supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, but at the same time, I don’t see people having these really important conversations about the structure, the architecture of the aid system and how it’s been designed on purpose to ensure inequities and to ensure that we don't get out of poverty. This is part of the neocolonial imperialistic design.”

Humanitarian organisations were created to respond to emergencies, but in responding to what are now chronic crises, they risk becoming part of the system that perpetuates situations of precariousness, said Gathara. “We shouldn’t be building resilience – we should be removing the reason why we say they need resilience.”

Even when it comes to remedying emergencies, current structures of aid delivery fall short. Speaking about the humanitarian response in post-earthquake Haiti, Bruce-Raeburn wondered how many aid workers could say that the money thrown at the recovery effort was “anything other than a band-aid on a gunshot wound.”

“We look at humanitarianism as a band-aid solution rather than looking at the interconnected risks and the structural issues of why those risks [are there] in the first place,” said Aarathi Krishnan, a humanitarian foresight advisor. “We say phrases like ‘leave no one behind’ as if it's an accident, not because it's actually a structured design of injustice in the first place.”

The old guard

The panelists noted that the discourse around international aid reflects who has the power to make choices on behalf of those in need, an exclusion that perpetuates inequality and dilutes the success of programs.

“When you're making decisions [about] where your money gets invested, it's not [done with] the people who are receiving that money,” said Krishnan. She added that while the aid sector has promoted funding for localisation, local people are continually left out of the conversation.

On the other hand, Bruce-Raeburn noted, pointing to what she described as a white supremacy culture in aid, “when white men talk in these NGO meetings, it's like [they are] the voice of God.”

“When white men talk in these NGO meetings, it's like [they are] the voice of God.”

The politics of being apolitical

Ali noted that the apolitical stance in Western conceptions of humanitarianism is particularly problematic when the very nature of crises themselves are political.

“The humanitarian system has been designed to be purposefully apolitical with these humanitarian principles [of impartiality and neutrality] as the backbone of it,” she said. ”We are asked to be neutral in a crisis while we watch people die and while we are not feeling a responsibility to save lives — [even] if that means taking arms.”

“The humanitarian principles are not fit for our future,” Krishnan added. “Our ideas of neutrality or even the UN Charter or human rights — we have a romanticized myth of remembering [them] and we forget the injustices in which [they were] raised.”

For Iweala, the UK foreign office’s recent absorption of the Department for International Development (DfID) was yet another indication of the illusion that humanitarian aid was ever apolitical. “DfID has always been an arm of British foreign policy and therefore an extension of what the state itself wants to achieve in the world.”

De-funding international institutions

While the panelists were encouraged that conversations about the structural problems underpinning aid are finally taking place, many were worried about whether this moment would lead to meaningful change.

Doubtful that large institutions could depart from the status quo, panelists suggested more disruptive tactics. “I think we’ve got to be more ambitious,” said Gathara. “Rather than trying to [create change] within rubbish systems, take a sledgehammer to the whole thing.”

“We need to unshackle ourselves from this idea that if we get more money, somehow we're going to resolve the problems of our people.”

Just like de-funding the police, Ali said, people working to alleviate international suffering should aspire to de-fund institutions created by the Bretton Woods Agreement of World War II allied countries — namely the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – which have been criticized for forcing their preferred economic policies on developing countries with little evidence of success.

“We need to unshackle ourselves from this idea that if we get more money, somehow we're going to resolve the problems of our people,” Ali said of NGOs in the Global South. “[We need to] start making demands on the system, saying ‘We want UN Security Council reform. We want you, the G77, our national governments to stop taking IMF and World Bank loans’.”

While Maxman was not ready to entertain the idea of withdrawing from international programs altogether, she said Oxfam does not accept US funding for its international work to maintain its independence.

Aid workers as activists

Moving away from a funding model that relies on Western donors would allow NGOs to stop acting like businesses and start acting like civil society, Ali said.

“The power is not going to be relinquished without a demand. We are too busy running after money to make that demand.”

She criticized aid workers busy in their “comfortable lives” doing “armchair activism” and called on them to be driven by social justice and their role as civil society.

Maxman highlighted Oxfam’s withdrawal from 18 countries, more meaningful partnerships with local humanitarian organisations, and a greater focus on solidarity and building a network of civil society “peers” as examples of how new ways of working could be built.

A diverse leadership pipeline in aid

Maxman, who led a transition from a leadership team at Oxfam that was predominantly white and male to one that is much more diverse, also pointed to leadership and governance as key levers for change.

Rondeaux noted that barriers to entry in the aid community, particularly in the form of unpaid internships, was hampering more diverse pipelines for leadership in humanitarian organisations.

By hiring like-minded individuals with similar professional and educational backgrounds, the aid sector has created an echo-chamber, Krishnan said, effectively eliminating the voices and experiences of those who do not have the same kind of access.

Krishnan also warned of the need for inclusivity in the development of whatever new vision of humanitarian action emerges from this moment of reflection. “There're so many of us that are talking about the future of humanitarian aid, but whose vision are we privileging in that re-imagination?”

The discussion ended with a concrete challenge from Ali to Maxman: to show leadership in supporting civil society in the Global South, to provide pipelines for local leaders, and to ask the questions required to reckon with the larger system.

“We don't need localization, which is in my opinion, is a very pejorative term,” Ali said. “What we need is a rather radical reckoning.” (Maxman responded that Oxfam is continuing to “push ourselves” in that regard).

More than 900 audience members shared their ideas on the way forward for an increasingly challenged aid sector. Read some of their thoughts and reactions to the panel here.

We will continue exploring the future of aid over the course of our #RethinkingHumanitarianism series this year. Stay tuned.

Illustrations by Ayumi Bennett.

ha-kp/js