A common refrain has been bandied about by many senior UN officials in the lead-up to the first-ever World Humanitarian Summit: the humanitarian system isn’t broken; it’s just broke.

If only there was more money, goes the argument, United Nations bodies and other aid organisations would be able to better support an unprecedented number of people – more than 125 million and rising – who are suffering as a result of natural disasters and man-made crises around the world.

If only it was so simple.

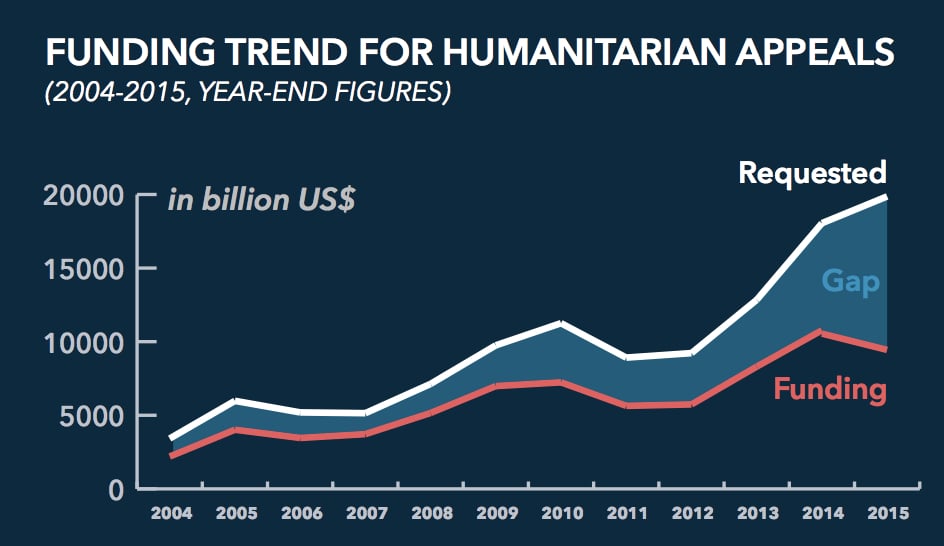

I co-chair the High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Finance, appointed last year by the UN Secretary-General to find solutions to a widening funding gap in responding to the world’s crises (the cost of responding to the number of people in need of aid skyrocketed from $2 billion in 2000 to $25 billion in 2014).

We estimated that gap to be in the order of $15 billion at the end of 2015. While more people than ever before are being reached with assistance, we are falling shorter and shorter of what is needed.

But here’s the catch: in months of consultations with fine, dedicated professionals from across the very wide field of humanitarian endeavour – many of whom risk their lives in the line of duty – as well as their colleagues and comrades in the development sector, refugees and displaced people, almost everyone with whom we spoke said that more money would not solve all the problems. Others went further by warning that such an approach may even entrench some of the dysfunctions in emergency response.

That’s because a dramatic growth in needs has transformed many simply structured, low-cost humanitarian organisations into complex trans-national bureaucracies.

We found evidence of competition between aid organisations in what resembles an over-crowded marketplace. Turf wars – where each organisation tries to position itself as the best implementer and therefore more deserving of donor funds – duplicate efforts and sap precious energy.

To be clear, humanitarians cannot solve political problems. The unrealistic expectations foisted upon humanitarians to “manage” protracted crises rather than finding solutions to them are the result of the actions – and often the failure to act – of those mandated to bring stability to the world.

However, humanitarians can better mitigate the effects if they find better ways to work together.

Our panel brought together people with vastly different expertise and strongly diverging opinions on what ails the global humanitarian aid system. For many months, we gathered our evidence and debated what does and doesn’t work.

A consensus emerged among our diverse panel members that it wasn’t enough to simply come up with additional funds. We felt strongly that more can and should be done to tackle the root causes of this tremendous humanitarian caseload to shrink the needs over time. But making the humanitarian sector itself more efficient would also go a long way.

As we note in our report, Too important to fail – addressing the humanitarian financing gap, putting humanitarian aid funding on a sustainable trajectory requires systemic change. And yet the ecosystem that has developed organically over many years, nurturing its own culture of vested interests, is resistant to change.

We ought to make the system simpler and more attuned to best practice. To make this happen, the donors and the implementers of aid need to come together to pioneer a model of collaborative efficiency that we decided to call (after much discussion) the Grand Bargain.

See: UN aid panel calls for 'grand bargain' on finance

The Grand Bargain is all about making more resources available on the frontline of needs, and spending less on administrative procedures that lead to waste because of duplications and overlaps. We desperately need to raise more money to fund humanitarian needs but this will only happen if we can get more bang for our buck.

The “sherpas” of a core group of donors and humanitarian and development organisations hammered out the fine detail of the Grand Bargain, which includes agreeing to less earmarking of funds by donors, joint needs assessments, harmonised reporting, joint procurement and increased use of cash as aid.

We agreed to targets, for example: by 2020, one quarter of humanitarian funding should go to local and national organisations directly and 30 percent of donor funds should be unearmarked.

This is a fine achievement and the proof so desperately needed that we are capable of changing our working practices and adapting our business model.

We can also take heart from the fact that, since the publication of our High-Level Panel’s report, the World Bank has partnered with the United Nations and the Islamic Development Bank to provide billions of dollars in financial support through leveraging grants to support refugees, host communities and recovery and reconstruction in the Middle East and North Africa.

But let me also issue a word of caution.

We found evidence of competition between aid organisations in what resembles an over-crowded marketplace. Turf wars duplicate efforts and sap precious energy.

The Grand Bargain, like other agreements likely to emerge at the Summit, is the beginning of the journey that must be made, not the terminus. Its purpose is to serve as a catalyst for the deeper system-wide change that we call for in our report. The UN and its 193 member states, the international organisations sheltering under its umbrella and those who cast their own shadows, the dynamic private sector, civil society and private individuals all have roles to play in reducing human vulnerability and our world’s fragility. Success will depend upon reaching a consensus around anticipation, transparency, research and collaboration.

I know it sounds like a tall order. But I am confident that if we can agree on the direction of travel and take the first steps together, our confidence will grow and we will reach the high ground. In a world increasingly vulnerable to shocks and strains, we can build confidence in our collective ability.

They say that Rome wasn’t built in a day. We must face up to the truth that it will take years of constant effort to accomplish what the WHS aims to achieve: a new start for humanity. We owe it to the more than 125 million people in need today of emergency assistance – and to all those risking their lives to deliver it – to make that start.

Kristalina Georgieva is vice president of the European Commission and co-chair of the UN Secretary-General’s independent High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Finance.

Other views on priority reforms at the World Humanitarian Summit:

Jan Egeland: The well-fed dead: Why aid is still missing the point