Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion on 24 February, UN agencies and major international organisations had a limited presence in Ukraine. Now, they’re scrambling to establish and scale up operations in the midst of escalating hostilities and spiralling needs.

Three weeks into the war, more than three million people have fled to neighbouring countries, an estimated 1.9 million have been internally displaced, and a total of 12 million are expected to need humanitarian assistance during the next three months, if the fighting continues.

Hundreds of thousands of people are trapped in cities under heavy Russian bombardment, and efforts to establish humanitarian corridors to evacuate civilians and allow for the delivery of much-needed aid supplies have so far had uneven results. At least 34 healthcare facilities have been damaged, often in deadly attacks, according to the World Health Organization.

The situation in the southeastern coastal city of Mariupol – surrounded by Russian forces – has become emblematic of the humanitarian consequences of the war: An estimated 350,000 people have been trapped for more than two weeks, facing severe shortages of food, clean drinking water, and medical supplies, and with limited access to electricity and heating.

The Ukrainian government says more than 2,500 people have been killed in Russia’s bombardment of the city. Casualty numbers are difficult to verify, but the true toll may be even higher. Authorities have had to resort to hastily burying the dead in mass graves. After several failed attempts, for the first time since the siege began, around 20,000 people were able to exit Mariupol in private vehicles along an evacuation route on 15 March.

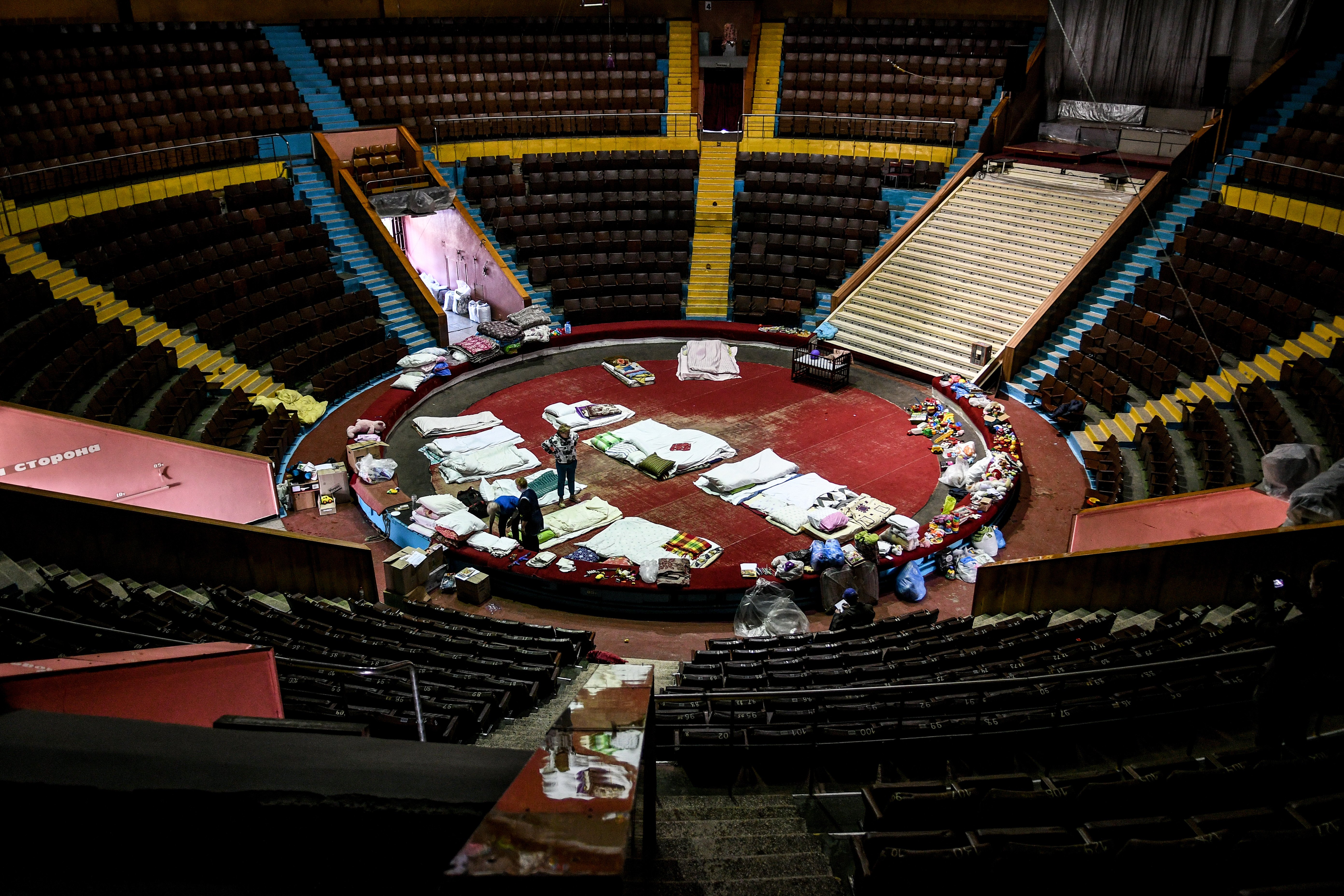

The humanitarian situation is similar in several other towns and cities in eastern and southern Ukraine. Under siege or bombardment, some civilians have been able to evacuate, but far more remain trapped – or are choosing to stay – amid worsening conditions.

Before the Russian invasion, 34 international NGOs and nine UN agencies had a presence in Ukraine. Their activities were primarily concentrated in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, where a conflict between Russian-backed separatists and the Ukrainian military had been simmering and driving humanitarian needs since 2014.

When the invasion began at the end of February, many international groups initially evacuated their foreign and local staff and temporarily suspended operations. Local volunteers stepped up to provide emergency relief in the first weeks of the fighting, but there are questions about how long their efforts can be sustained, and the international aid response is starting to pick up steam.

Read more → In Lviv, volunteers shoulder humanitarian response, but for how long?

International organisations that already had a presence in Ukraine have regrouped and are expanding and redirecting their operations to meet new and vastly expanded needs.

“It was difficult to immediately deploy our teams to provide assistance where it was needed,” Oleksandr Vlasenko, a media relations officer for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which has been operating in Ukraine since 2014, told The New Humanitarian. “Therefore, we focused on providing assistance in those places where our teams were already present [in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions].”

The ICRC is in the process of increasing its staff presence and establishing bases of operation in other parts of the country, while providing more support to the Ukrainian Red Cross, which already has a widespread presence.

Meanwhile, many other international organisations are setting up operations in Ukraine for the first time. “We are starting from scratch in a time of a heightened conflict,” said Jakob Kern, deputy chief of staff for the World Food Programme (WFP).

To deliver assistance to those most in need, these organisations, and others like them, face a series of logistical and security challenges – from the threats posed by ongoing fighting, to shortages of vehicles and drivers, to increasing congestion at an airport in Poland that has become a key landing point for humanitarian aid and other assistance bound for Ukraine.

Logistical hurdles amid a growing response

Ukraine is the second largest country in Europe – only Russia is larger. Under normal circumstances, it takes more than 20 hours to drive from west to east. With roads and bridges destroyed by the war and ongoing shelling, moving humanitarian aid across those long distances is no easy feat.

Most NGOs have set up their bases of operations in Lviv, in the far west of Ukraine, about 40 kilometres from the Polish border. Lviv has been relatively untouched by the fighting so far – although that may still change. The UN has established a travel route for humanitarian supplies to reach the city from Rzeszow, Poland – about 80 kilometres from the border – and has secured storage space in both locations.

As the number of humanitarian groups launching and scaling up their responses has grown, the airport in Rzeszow has become increasingly congested. There have also not been enough trucks and drivers available to move supplies across the border, while there’s stiff competition over the transportation and logistical resources that do exist.

To solve some of these issues, the UN is recommending that aid groups find alternative landing points for humanitarian supplies being flown into Poland and is looking into using the railways to transport supplies into Lviv and other parts of Ukraine.

Having supplies enter Ukraine via Lviv means having to move them over long distances to reach the populations in the centre and east of the country hardest hit so far. To avoid the logistical snarl at the Ukraine-Poland border and position themselves closer to those needs, some smaller organisations are setting up operations in the Black Sea port city of Odesa and moving supplies in and out of neighbouring Moldova.

“We chose Odesa because of the lack of response here,” said Tom Robinson, an emergency response manager with Swiss NGO HEKS. “A hub in Odesa makes sense in a forward-looking approach: You can access the frontline areas and not have to go across half the country to do it.”

Although the war has yet to fully reach Odesa, an attack may be imminent. Residents are preparing to defend the city as the Russian army moves westward along the Black Sea coast.

For the time being, HEKS has been able to support local aid initiatives by hiring Ukrainian team members, providing subgrants to build the capacities of local NGOs, and setting up supply lines to send provisions such as vegetables, grains, and medicines by train to hard-hit areas like the northeastern city of Kharkiv.

“To us, the most prevalent needs are the frontline needs… the needs of people who are not receiving any kind of aid delivery because it might be deemed too risky,” Robinson told The New Humanitarian. "If people are there, responding [to aid needs], and if journalists are there – then absolutely humanitarian emergency response organisations should be there.”

But as the conflict increasingly encroaches into the region and accessing resources around Odesa becomes more difficult, sustaining this effort will be a major challenge. “The main question is: Can we get supplies from these areas? Can we set up supply lines to ensure that the provision of supplies can be ongoing?” Robinson said.

Security concerns, humanitarian corridors, and local partners

The biggest challenge to the rollout of the international humanitarian effort, however, is the ongoing fighting, which puts the delivery of aid at risk. “Access and security of staff has always been an issue, and has not become easier,” said Kern, from the WFP.

Hundreds of tonnes of aid, including food, medicine, blankets, hygiene products, medical trauma kits, and – ominously – more than 5,000 body bags, has started arriving. Some of it is already being distributed across the country, but safe passage for humanitarian supplies is still limited by “sporadic fighting and indiscriminate attacks on roads and infrastructure”, according to the UN.

On 14 March, a humanitarian convoy en route to Mariupol had to turn around due to shelling – the latest in a string of such incidents – and another convoy was reportedly looted on 12 March.

The ICRC and UN agencies are engaged in negotiations to try to ensure safe passage for aid supplies as well as humanitarian corridors for civilians to leave areas being bombarded. “This issue is constantly discussed with each of the parties to the conflict,” said Vlasenko, from the ICRC. “For us, the key is the safety of people who want to leave unsafe cities.”

As of 14 March, more than 150,000 people had been evacuated through humanitarian corridors, according to the Ukrainian government. For its part, the Russian government says it has evacuated around 270,000 people towards Russia. The UN, which reported the numbers, said it does not have the means to verify their accuracy.

Meanwhile, there have also been reports of Russian soldiers firing on evacuation convoys, and hundreds of thousands of civilians are still living in frontline cities and towns, either by choice or because they have no way out. The effort to deliver aid to those most in need in these areas is a race against time, and the easiest point of entry for many international aid groups is through partnerships with Ukrainian NGOs and local civil society organisations.

“The biggest challenge for operations inside Ukraine, especially in conflict areas, is the lack of presence of humanitarian partners for the distribution of food and vouchers,” said Kern. To address the issue, “WFP is in discussion with NGOs, civil society, and churches to find ways to fill the gaps,” he added.

The NGO World Vision is following a similar approach, as it provides assistance to refugees crossing into neighbouring Romania through its existing network while looking to launch operations inside Ukraine. “We have a national office with 200 staff established [in Romania] for many years, [so] it made sense for us to start supporting the refugees coming here from Ukraine,” said Isabel Gomes, the group’s global director of humanitarian operations.

To provide assistance to those still in Ukraine, World Vision is working with partners who cross the border to deliver aid and then return to Romania. “What we’re looking for moving forward is having partners [inside Ukraine],” Gomes said. “Right now, it’s in and out. But we have to have a better presence on the other side.”

Eventually, the group wants to set up a base in Lviv, but the quickly evolving war makes that kind of longer-term planning difficult. “The situation is so fluid,” Gomes added.

Even for NGOs with a long-standing presence in Ukraine, like the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), the sheer scale and fast spread of the conflict has led to the rollout of new programmes. The group is now using WhatsApp and SMS to conduct large-scale needs assessments, coordinate the distribution of cash and non-food items, and to provide counselling and legal aid.

NRC started mapping out different scenarios in December, but considered a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine the least likely outcome.

“This is an incredibly fast-developing displacement crisis,” Ole Solvang, NRC’s director of partnerships and policy, told The New Humanitarian. “This came as a surprise to us, as it did to the entire humanitarian industry. In hindsight, it's easy to say we all should have been better prepared, but I’m not sure that everybody believed that this would happen.”

Little respite

Aid is beginning to trickle into hard-hit areas.

Rita, a 51-year-old caregiver whose full name is being withheld to protect her identity, lives in Selyshche Zhukovsʹkoho, a residential area on the outskirts of Kharkiv. Russian shelling has pounded the neighbourhood for weeks, and many of its buildings have been severely damaged. Rita and her husband have been living for the most part in a basement with about 20 other people from surrounding buildings and occasionally coming to the surface to stock up on food.

In a recent phone call with The New Humanitarian, Rita said food aid boxes from international donors were now being distributed in the neighbourhood. Electricity had recently been restored, and there was still running water – although it was sometimes interrupted and hot water hadn’t been available almost since the beginning of the invasion. “We wash once every two or three days because it’s impossible in the apartment; it’s so cold,” Rita said.

“I think now no one is starving because some food is being brought in; not necessarily something expensive, but for porridge,” Rita continued.

However, the arrival of a few basics offers little respite from the physical and psychological toll of the ongoing war. People’s nerves are frayed. In Selyshche Zhukovsʹkoho, there are fights over limited grocery supplies, and some women come out onto the streets and yell in rage. After weeks of constant shelling, Rita said it was getting to her too: “I can't stand it anymore.”

Additional reporting by Lidiya Huzhva in Dnipro, Ukraine. Edited by Eric Reidy.