After months of relative calm, COVID-19 has again been coursing through much of the Middle East and North Africa, posing a major challenge for countries with low vaccination rates and healthcare systems that were often in bad shape even before the pandemic hit.

This is not entirely unexpected: The World Health Organisation warned in mid-July that infections were rising across the region, with the particularly contagious Delta variant spreading fast. And that was before the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha, which this year ran from 19-23 July and traditionally includes large gatherings.

Since then, infections have shot up in Libya, Morocco, Lebanon, and Iran – where on Monday COVID-19 deaths hit a daily high of 665 – as well as in places like Tunisia and Algeria, where the numbers have since dropped off but have already had serious consequences.

Vaccination rates are low almost across the board, and for a variety of reasons: limited deliveries from the UN-backed COVAX facility, scepticism of the jabs, and the inability of many countries to purchase doses after their economies were hit hard by the pandemic. Israel (but not, for the most part, occupied Gaza or the West Bank) and the Gulf countries are notable exceptions.

In early August, Dr. Haytham Qosa, head of health in the Middle East and North Africa for the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), cautioned that vaccine inequity is a serious threat in a region already dealing with a litany of problems.

“Leaving countries behind on vaccines will only serve to prolong the pandemic, not just in the region, but globally,” Dr. Qosa said. “Many countries are facing other vulnerabilities, including conflict, natural disasters, water shortages, displacement, and other disease outbreaks. This makes people even more vulnerable to the devastating impacts of COVID-19. This alone should be a reason enough for global solidarity to ensure equitable vaccine access in the region.”

Libya: Soaring caseload amidst supply shortages

COVID cases: 286,894

Deaths: 3,956

Vaccinations: 764,233 doses

Percentage of population vaccinated*: 5.6 percent

As cases soar, health workers in Libya say they’re still struggling with the same overarching obstacle they faced at the start of the pandemic: a decade of armed conflict and chaos has crippled the country’s healthcare system.

“In our hospital, we have outdated and broken medical equipment. You can find dusty ventilators locked in a room. Nobody is able to use them,” said Dr. Nasser, a physician at Tripoli Central Hospital – the Libyan capital’s second largest.

Dr. Nasser, who asked that his surname not be published, said many doctors aren’t being regularly paid by the country’s six-month-old interim government, and that 17 months on from Libya’s first confirmed coronavirus case, “there is still a severe shortage [at his hospital] of lifesaving medicine and supplies, including gloves and masks.” Libya has not yet confirmed an official case of the Delta variant, but the WHO says it is “suspected” because of its presence in neighbouring Tunisia and Libya.

Libya, which has a population of around seven million, has so far received around 2.7 million doses of vaccines, including 292,890 doses of AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines via COVAX, as well as a reported 900,000 doses of Russia’s Sputnik V from third countries and two million doses of China’s Sinopharm. It has administered more than 764,000 doses so far, in a country of around seven million people.

Several Libyans told The New Humanitarian they were frustrated at how the government has organised the vaccination campaign. “My family and I signed up to get the vaccine, but we never heard back,” said a recent medical school graduate from the second city of Benghazi who asked not to be named.

Dr. Tamadur Almahdi, who works for Speetar, a Libyan telemedicine platform that offers online consultations, said “a lot of people are asking about the vaccine's safety, efficacy, effectiveness, and protection.”

COVID-19 vaccination is even harder for the more than 600,000 migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in Libya, with discrimination in accessing healthcare services a longstanding barrier for this population, who also face detention, torture, rape, and other abuses.

Mohammed Mussa, a Sudanese refugee from Darfur who lives in Surman, a town in northwestern Libya, said getting vaccinated is just not his top priority. “If I look at my situation, I don’t see where the importance of the vaccine fits in,” he told The New Humanitarian. “Right now, I don’t even have enough money for food, rent, or medical care.

Sara Creta, long-time reporter on Libya, currently in Darfur

Lebanon: Lights out, economic worries

COVID cases: 584,896

Deaths: 7,988

Vaccinations: 2,221,656

Percentage of population vaccinated*: 16.4 percent

With its economy in tatters and some hospitals now running out of electricity and medications because of subsidy cuts, Lebanon is barely able to respond to new COVID-19 cases, which have been increasing at a fairly steady rate since late June.

Two weeks ago, Dr. Abdulrahman Bizri, the head of Lebanon’s COVID-19 vaccination committee, said the new Delta variant had been identified in 60 percent of new cases.

Lebanon’s financial crisis, which began before the pandemic but was worsened by it, has been disastrous: The local currency has lost 90 percent of its value since September 2019, and food prices are up 400 percent, among the highest worldwide. Today, about half the population lives in poverty.

That may be among the reasons the country’s COVID-19 policy has mostly focused on mitigating the economic effects of the pandemic: Unemployment skyrocketed following its first lockdown in March 2020, and there have been few subsequent lockdowns despite rising cases. The government largely allowed the country to stay open in the summer and winter of 2020, when tourists poured in, and restaurants, nightlife, and hotels were allowed to function at almost full capacity.

This temporarily helped breathe life into the economy, but it also allowed for intermittent surges in cases, including this one – the largest since December 2020. “We never put into place an effective long-term strategy,” Dr. Jade Khalife, a Lebanese physician who specialises in health systems, told The New Humanitarian. “You have repetitive cycles of surges every five or seven months… with yo-yo partial or full lockdowns.”

Doctors and hospital administrators have cautioned that they would be unable to cope with a full-on Delta variant wave, should current trends continue. When cases skyrocketed last January, some hospitals treated patients on stretchers used as makeshift beds, and had to reallocate other wards for coronavirus cases. Due to the lack of capacity and oxygen shortages, patients with less severe symptoms were sent home.

Lebanon’s vaccine rollout has been slow, and one vaccination drive was postponed due to electricity issues, but rates are relatively high for the region: Just over 32 percent of the population registered for the vaccine, and less than 21 percent of the population is fully vaccinated (other sources put this number closer to 16 percent). According to data from UNICEF, Lebanon’s cash-strapped government has secured a total of 2.64 million vaccine doses, including 292,800 of the AstraZeneca vaccine from COVAX, and 588,510 doses of Pfizer. Some of the Pfizer doses have come from COVAX and most thanks to money from the World Bank, which reallocated $34 million in emergency funding from an existing healthcare project to pay for them.

Meanwhile, Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine is available through a private distributor, which has mostly been selling them to businesses. There may be more Sputnik V available soon: A Lebanese pharmaceutical company announced in early August it had signed a deal to produce the vaccine locally.

Dr. Khalife says Lebanon can’t just rely on travellers and sick people self-isolating, especially as mass vaccination hasn’t happened yet. “The weakness of over-relying on vaccines has been exposed already, because our access to vaccines was already quite weak, and we started later than other countries,” he said. “We need to focus on preventing cases, and adopt a policy of containment and move towards elimination.”

Kareem Chehayeb, Beirut, Lebanon

Tunisia: A deadly wave abating?

COVID cases: 626,750

Deaths: 22,025

Vaccinations: 4,690,354

Percentage of population vaccinated*: 20.3 percent

Tunisia’s dramatic third wave of COVID-19 became so catastrophic by late July that it sent protesters into the streets, with the country’s president dismissing the country’s then-prime minister and suspending parliament in a move denounced by critics as a coup.

President Kais Saied said his actions were necessary to fix the country’s faltering economy, and to put a stop to a coronavirus death toll and caseload that had soared to new heights: Morgues had been filling up, hospitals were overwhelmed and running out of oxygen, and grave-diggers were working around the clock.

While cases have since dropped off, Tunisia has the highest recorded death rate per capita in the Middle East and North Africa, with 22,025 deaths in a country of around 12 million. In early August, the WHO said more than 90 percent of the country’s infections were due to the Delta variant, and “being fuelled by low adherence to public health and social measures, as well as low vaccination coverage”.

Since then, the country has kicked off a massive vaccination drive, having received – or been promised – several million doses from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Algeria (which has been struggling with its own wave). Tunisia has also received 1.9 million doses of Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Moderna vaccines from COVAX.

Tunisia and neighbouring Algeria have also been forced to allocate limited resources to fight devastating wildfires in soaring summer temperatures. “Climate change is here. It impacts people across the globe every day,” Anne Leclerc, from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, said in a statement last week. “Combined with the recent surge of COVID-19 cases in the region, we are tackling multiple crises simultaneously. The combination of these is stretching already strained healthcare systems to their limits.”

Iraq: A third wave, and concern for the next one

COVID cases: 1,793,372

Deaths: 19,815

Vaccinations: 2,102,550

Percentage of population vaccinated*: 2.7 percent

In Iraq, health workers told The New Humanitarian they had been taking major risks to treat the sick throughout multiple waves of the virus, and that even the start of vaccinations hadn’t necessarily reduced their fears.

That’s because its public healthcare system – marked by dilapidated infrastructure, chronic underfunding, a shortage of medical staff, and a serious lack of trust – was recently hit by two deadly fires at facilities treating coronavirus patients. An April fire at a Baghdad hospital killed at least 82 people, and the death toll from a July hospital blaze in a COVID-19 isolation ward in the southeastern city of Nasiriyah is at least 92.

Iraq has received 2.9 million vaccine doses from COVAX, including 1.1 million doses of AstraZeneca and 500,000 Pfizer via COVAX, plus 550,000 more doses of Pfizer from other countries or agreements. It also has 750,000 of Sinopharm. Vaccination campaigns are mostly taking place in major cities and hospitals, which has raised some concern about crowding and the possibility of infection at these centres.

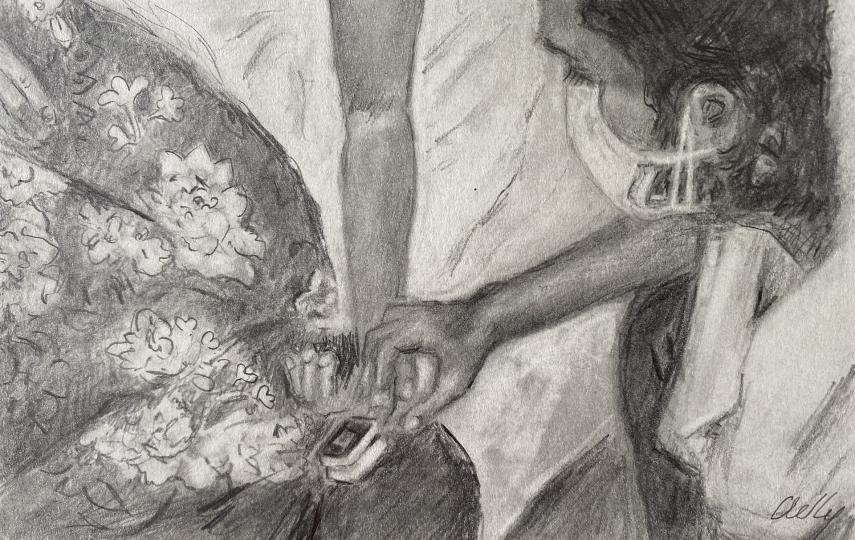

Noor Hazem, a nurse in Baghdad, told The New Humanitarian she has been constantly terrified about bringing the virus home. “I’m in direct contact with the infected, so since the start of the pandemic I’ve been preparing myself to say goodbye to my family forever.”

While Hazem said “the vaccine saved my life”, she added that the April and July disasters had raised new worries for her: “I now wonder about how to avoid getting burned in the hospital where I work.”

Not everyone has been as willing as Hazem to take the vaccine. Ali Kareem, 30, a doctor at Baghdad’s al-Yarmouk hospital, told The New Humanitarian that a worrying number of people have declined to be vaccinated. “We are still facing the height of the third wave, due to people refusing to be vaccinated,” he said. “The situation will get worse,” he added. “We don’t have enough beds for patients, and we’re unlikely to be able to provide them with oxygen or care” as the wave progresses.

The situation is not helped by rumours that the vaccines cause infertility and are a way for Western countries to spy on the population. However, the recent increase in infections and the government’s insistence that people entering official institutions show a vaccine card appears to have increased uptake.

One aid worker, who requested anonymity to speak freely, said the aid community was trying to immunise the more than 248,000 refugees and asylum seekers and 1.3 million internally displaced people in Iraq; but she said refusal rates had been high (although it’s hard to know the actual vaccination rates among these groups because they can’t register independently for the jabs). “We are working hard through awareness sessions about the virus,” the aid worker said. “The infection inside the camps is considered a time bomb… [because] people share cooking tools, food, and bathrooms.”

Health workers were also concerned they would see more cases of the Delta variant because of Muharram, a month that has particular significance for Shia Muslims and began this year on 10 August. This period sees tourists flock to Iraq from Iran and Pakistan, a millions-strong pilgrimage to the southern city of Karbala, and gatherings elsewhere in the country.

Sanar Hasan, Baghdad, Iraq

Yemen: A divided country and denial

COVID cases: 7,308

Deaths: 1,405

Vaccinations: 311,483

Percentage of population vaccinated*: 0.5 percent

Yemenis have suffered at least two serious waves of COVID-19, with treatment options extremely limited by a healthcare system that has been decimated by six years of war, and fear of seeking help compounding the problem.

Officially, infections and deaths in both the Houthi rebel-run north (including the capital city of Sana’a) and the internationally recognised government-run south are relatively low and stable at the moment. But recent reports say the Houthis have opted to keep the real case numbers secret (they suggest that releasing this information would generate unnecessary fears), and when vaccines arrived in the country – 360,000 doses of the India-produced Covishield (licensed by AstraZeneca) via COVAX in March – they allowed only 1,000 doses into the part of Yemen they control.

Dr. Abdurrahim al-Murri, who works at the COVID-19 isolation centre at Sana’a’s al-Kuwait hospital, said what appeared to be a second wave had slowed by the end of Ramadan – on 12 May – but had begun to rise again by the start of Eid al-Adha, on 19 July. He said it’s hard to know exactly how many people have died because the Houthis haven’t released any data, but “we think it’s higher than at this time last year”.

The centre where he works closed temporarily in October because admission rates were so low, but now it is full. Dr. al-Murri said it has enough supplies, and that the “main challenge now seems to be the virus’ mutating nature”.

Still, he said, the local community doesn’t trust isolation centres, in part because of widespread rumours last year that Houthi-run hospitals were killing patients on purpose with a lethal injection.

“Most patients arrive too late; we can’t help them survive [at that point],” said Dr. al-Murri, adding that when he asks patients why they waited so long to get help, they mention the lethal injection rumour.

In the south of the country, where in April and May 2020 Aden was believed to be one of the cities with the highest infection rates in the world, cases also appear to have been rising since Eid al-Adha. Dr. Yaser Alwai, director of the COVID-19 isolation centre at Aden’s al-Sadaqah hospital, said that while he has more cases than this time last year, “the team is a bit more organised and prepared.”

Still, he’s concerned about another wave, what the Delta variant will mean for Yemen, and an ongoing shortage of ICU supplies. As in the north, he said, patients often “arrive too late for treatment”.

Dr. Alwai said that when vaccinations began – targeted at health workers and people who need to travel outside Yemen – people were reluctant to get their jabs. “The common person, even some medical staff, were concerned about possible side effects and complications [from the vaccine]. A lot panicked.” Uptake increased, he said, when Saudi Arabia began requiring people who work in the country to show proof that they had been vaccinated.

Still, Dr. Alwai said, misinformation and rumour remains a problem: “A significant portion of the population is denying that COVID even exists. They also have a great deal of fear of seeking treatment at isolation units, until they experience it firsthand.”

Shuaib Almosawa, Sana’a, Yemen

*Numbers for percentage of population vaccinated use the assumption that every person needs two doses.

Data source for reported infections, deaths, and vaccinations.

Edited by Annie Slemrod.