The International Court of Justice in The Hague this week ordered Myanmar to “take all measures within its power” to protect its Rohingya minority from genocide.

It’s the first time a global court has pronounced judgement against Myanmar for the 2017 military purge of more than 700,000 Rohingya from their homes in Rakhine State.

Myanmar’s military is accused of massacring civilians, sexual violence, torture, and other abuses in a bid to force hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee. For years, authorities in Myanmar have stripped the Rohingya of citizenship and basic rights, and some 600,000 Rohingya still in Rakhine State live under apartheid-like restrictions.

Thursday’s ICJ order is an emergency injunction in a larger case, launched by The Gambia last year, that accuses Myanmar of violating the Genocide Convention. That case will likely take years, but rights groups see Thursday’s interim ruling – meant to prevent further violence and preserve evidence – as a significant step in pressuring Myanmar after years of global inaction.

The “decision sends a message to Myanmar’s senior officials: the world will not tolerate their atrocities, and will not blindly accept their empty rhetoric on the reality in Rakhine State today,” said Nicholas Bequelin, a regional director for Amnesty International.

The ICJ also ordered Myanmar to submit twice-yearly reports on what it’s doing to enact the ruling.

But it’s unclear what effect the ICJ order will have. Myanmar has largely denied most allegations levelled against its military, blocked UN investigators from setting foot in the country, restricted aid access in Rakhine, and refused to recognise the authority of the International Criminal Court, whose prosecutor is pursuing a separate investigation into alleged deportation crimes.

Earlier, Myanmar released a summary of its own enquiry on the Rohingya crisis: it acknowledged that soldiers may have committed “war crimes” but denied any “genocidal intent” against the Rohingya.

In an opinion piece published in the Financial Times before the ICJ ruling, Myanmar’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, suggested international investigations have relied on “inaccurate or exaggerated information”, and called “for domestic justice to run its course” instead.

Khin Maung, director of the Rohingya Youth Association in Bangladesh’s refugee camps, called Myanmar’s denials “yet another whitewash of the crimes against us”.

Here’s a selection of our reporting that explores the roots of the Rohingya crisis, its ongoing impacts in both Myanmar and Bangladesh, and the long path toward investigating and prosecuting rights abuses:

What’s behind a flurry of legal bids to prosecute Myanmar for genocide?

Three legal bids, three courts, and three separate roads to examining Myanmar rights abuses.

Q&A: How a legal challenge on Rohingya deportation could redefine the bounds of international justice

A war crimes prosecutor uses a legal loophole to investigate anti-Rohingya violence.

In a Myanmar village, a bamboo fence separates Rohingya and Rakhine neighbours

‘It's better we don't live together’: Rohingya families live with apartheid-like restrictions, but economic ties still bind divided communities together.

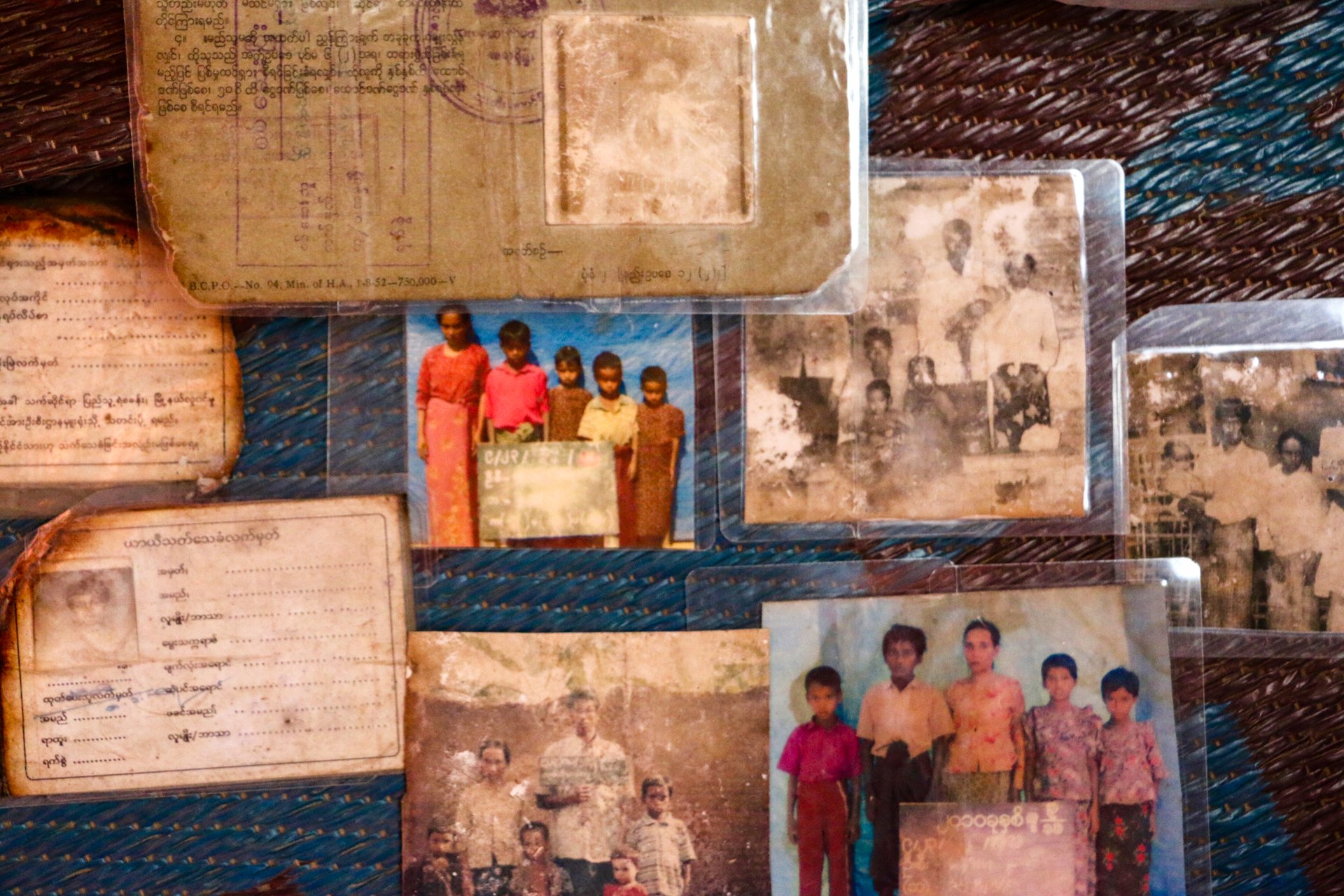

Identity and belonging in a card: How tattered Rohingya IDs trace a trail toward statelessness

After fleeing Myanmar, refugees cling to old documents as proof they belong to a country that now rejects them.

Male rape survivors go uncounted in Rohingya camps

Men and boys are also survivors of sexual violence. But they’re largely overlooked during crises – including in Bangladesh’s refugee camps.

Why Rohingya women and girls are risking dangerous smuggling routes

Years of rights abuses and restrictions, limits on education, and new safety threats are pushing more Rohingya women and children to risk perilous boat journeys.