After increasingly dire warnings that Yemen is on the verge of (or in the midst of) famine, the Saudi Arabian-led coalition has announced it will reopen on Thursday a key port and airport for “humanitarian and relief efforts”, ending a partial blockade lasting more than two weeks.

Hodeidah port and Sana’a airport were shut down after Houthi rebels fired a missile at Riyadh earlier this month, and the coalition responded by closing all routes into Yemen, saying it was to prevent weapons smuggling.

The situation inside Yemen deteriorated quickly and was feared to get much worse, with a run on fuel, water shortages, and concerns that food stores would empty within the next few months. Humanitarians have been tweeting about the impending disaster with the hashtag #LetAidIn.

The semi-opening of Hodeidah and Sana’a is welcome news, if indeed the ships and planes full of food and vital medical supplies are really granted entry. But many Yemenis will need more than aid if they are to survive this crisis; they'll need commercial imports too.

The importance of Hodeidah

Forces loyal to internationally recognised (but deposed) Yemeni President Abd Rabu Mansour Hadi, backed by the Saudi-led coalition, have been trying to oust Houthi rebels and fighters who side with former president Ali Abdullah Saleh for more than two and a half years.

Even before the war, Yemen was the poorest country in the Arabian Peninsula, with 4.5 million Yemenis classified as "severely food insecure" in 2014.

Yemenis rely on imports for 80-90 percent of their food, including two key staples – wheat and rice – the majority of which comes through Hodeidah and the nearby smaller (and also shuttered) Saleef port.

Wheat is mostly shipped to Yemen unprocessed and in bulk and processed at Hodeidah, which, despite its diminished capacity thanks to airstrikes, still has working silos and grain mills. Vitally, there’s no indication yet that the Saudis plan to re-open this port to commercial imports.

Aden, under the Saudi coalition’s control, was re-opened last week for commercial trade and aid deliveries, but it only has 40 percent of the milling and storage capacity of Hodeidah. Other seaports were never really closed, but are too small to handle large-scale shipping anyway.

If traders are forced to use Aden for commerical imports, they may have to pivot to packaged flour or rice. A shift to flour would likely be costly, and that cost would be passed down to the Yemeni consumer.

But it’s not only rising prices that are a concern. A Yemeni source familiar with the matter told IRIN that Aden is also unlikely to be able to scale up quickly enough to handle the amount of imports that could soon be directed its way. Issues include the union that controls the boats and staffing, and the fact that the port’s customs department only works part-time – when the air conditioning in the hangar it uses is actually functioning.

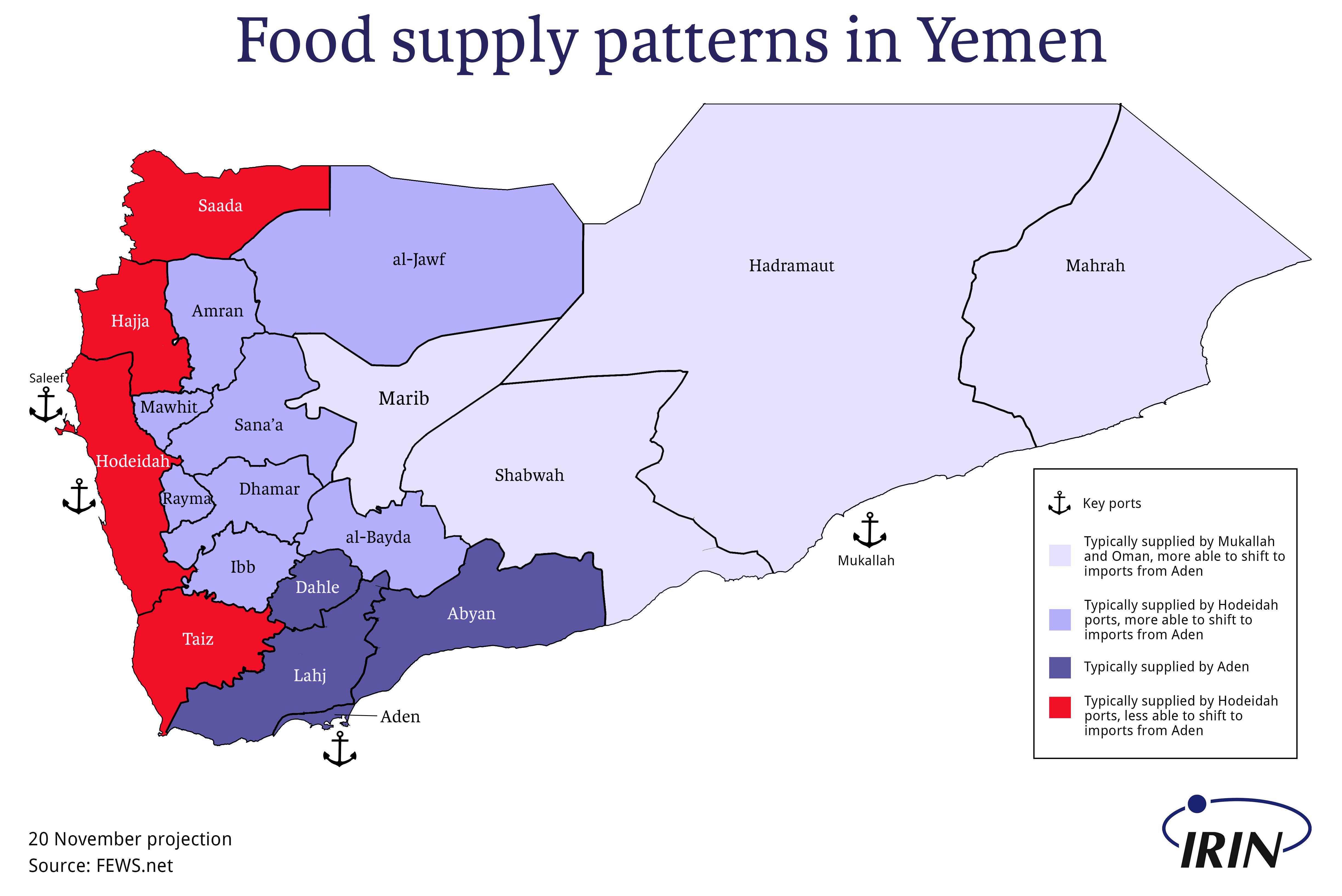

Then there’s the problem of location. By UN estimates, 71 percent of the nearly 19 million Yemenis who need assistance are in Houthi-Saleh controlled areas. Getting food – or aid for that matter – to them from Aden, which is in the hands of various competing forces nominally loyal to Hadi – is extremely difficult. The source told IRIN there are dozens, even as many as 100 checkpoints on the route that can handle lorries between Aden and Houthi-Saleh run Sana’a. Hodeidah and Saleef, which fall in Houthi-Saleh territory, are the natural fit for bringing food to this population.

The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), which is funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), recently reported that “even if throughput [through Aden] improves significantly, famine will remain likely, once stocks are depleted, in areas that had relied on food imports from [Hodeidah] ports, but that are less able to shift towards Aden as a source of staple food.”

It added that even for areas that are able to access imports from Aden, the famine risk remains, given the likely increased competition for goods.

There was already a blockade

All of this is not to mention that getting aid and commercial goods into any Yemeni port has been incredibly difficult since the war began in 2015.

A September Human Rights Watch report said the coalition’s restrictions on imports “have delayed and diverted fuel tankers, closed a critical port, and stopped life-saving goods for the population from entering seaports” controlled by Houthi-Saleh forces.

Even before the deterioration of the past two weeks, large parts of the country couldn’t get enough food to eat – although the use of cash aid and vouchers has reportedly increased demand (or rather, increased the purchasing ability of people who already had the demand), meaning traders are more willing to risk sea or land routes and bring food in.

The Houthis are also accused of diverting aid and denying humanitarian access (especially in Taiz), but they do not control the entry of large amounts of aid and food imports to coalition/Hadi-run parts of the country.

Diplomacy at work?

The re-opening of Sana’a airport (mostly for aid workers and medicines) and Hodeidah port would seem to represent a preliminary success in a two-stage UN plan: Get aid running again first then step up negotiations to try to break the deadlock on commerical imports.

Before the Saudi announcement on Wednesday, UN humanitarian coordinator in Yemen Jamie McGoldrick told IRIN the world body had proposed “the separation of humanitarian and commercial shipments right now, because there can be no threat or risk on anything humanitarians have brought in”.

But the premise of the Saudi blockade has also been called into question, even if Iran is widely accused of supplying the rebels with some weapons.

A UN panel of experts found, before Aden and other coalition-held ports were reopened, that there was no evidence that a short-range ballistic missile of the type fired at Riyadh had been transferred to the Houthis by Iran (as alleged), and accused the coalition of using a 2015 Security Council resolution intended to prevent arming the Houthis "as justification for obstructing the delivery of commodities that are essentially civilian in nature".

McGoldrick said the UN mechanism to inspect commercial ships could be possibly strengthened – in fact UN Secretary-General António Guterres sent a letter to the Saudi envoy to the UN on 16 November asking him to end the blockade but also offering to send a team to Riyadh to discuss the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) that screens all cargo headed for Yemen.

It also offered to send a senior UN team to discuss arrangements at Hodeidah port and Sana’a airport.

At the time of publication, IRIN understood that the Saudis had not replied to the letter.

However, in its statement announcing the easing of the blockade, the coalition said it “renews its call for the United Nations to urgently send a team of experts to meet with their counterparts… to review and enhance… UNVIM… in order to implement the best practices that will protect the people of Yemen, and facilitate the entry of aid and humanitarian shipments, while preventing the Houthi militias from smuggling missiles to target neighbouring countries.”

As of Wednesday night, IRIN could not confirm if and when much-needed aid (including vaccines and medication) would begin to flow back into Yemen.

But the fact remains that there are massive shortfalls in food, fuel (key for pumping water), and medical supplies that the humanitarian community will never be able meet on its own.

Yes, #LetAidIn, but also, and urgently, #LetTradeIn.

(TOP PHOTO: An 18 month-old with severe acute malnutrition and respiratory problems in northern Yemen. Save the Children)

as/ag