John Ngah* is a keen amateur footballer, but at the end of each game, when his team mates head off to their families, he heads back to the Buea Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration Centre (DDRC) – his home for the past two years.

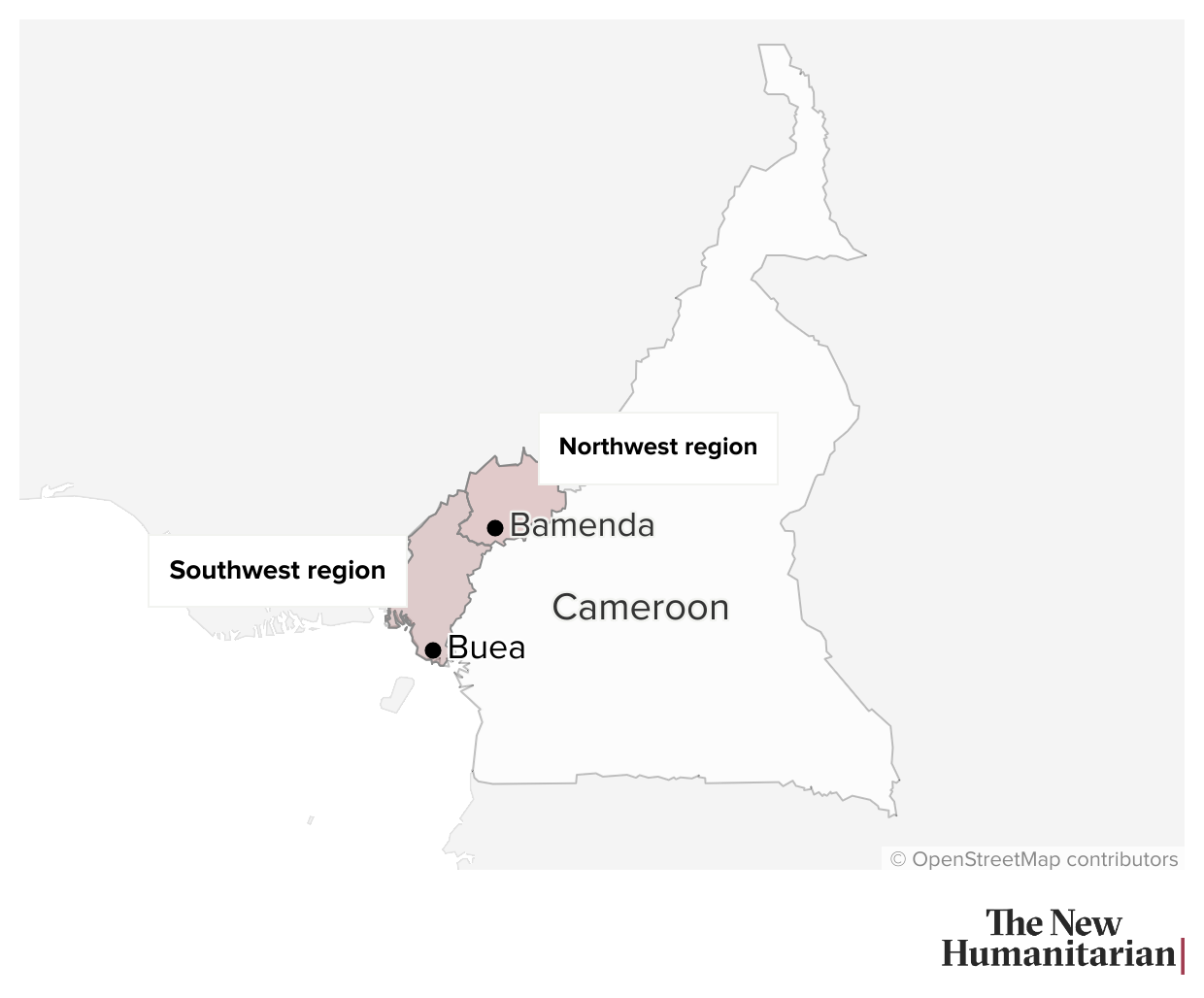

The 22-year-old is a former combatant in a separatist movement that since 2016 has been fighting for the independence of the country’s two English-speaking Northwest and Southwest regions, otherwise known as “Ambazonia”.

He joined the “Amba boys” in 2018, frustrated by what he regarded as the “marginalisation” of anglophones in the majority French-speaking country – especially when it came to finding public sector jobs – and the “intimidation” he said he witnessed of young English-speaking men by the security forces.

John Ngah – DDRC Buea

“There were [anti-government] protests and marching in Mbonge [in the Southwest region] in 2018. The military moved door to door, and when they [saw a young man] they would arrest you. But some people were also summarily killed – so the pressure was too much. It was the intimidation from the military that made me join. We used to say ‘It’s better to die as a hero’. Instead of waiting to be killed, we started fighting them before they came for us.

“The same year the crisis started, they launched the police [competitive entrance examinations] and so many went in for police, gendarme, and BIR [the elite Rapid Intervention Battalion] exams. Some who did not pass chose the other way [joining the separatists]. It was like they were taking only francophones. I myself wrote the exam for the police. I came to Buea to submit everything, but down the line either you don’t have money [to bribe] or you are anglophone [and they reject you].”

Two years on, disillusioned by his experience in the bush, and by what he saw as a secessionist struggle that had lost its direction, Ngah made his way to Buea, the main city in the Southwest region, and gave himself up – swayed in part by government promises of job training and reintegration.

“The movement has changed,” he told The New Humanitarian. “It’s now about kidnapping, stealing, and demanding ransoms [from civilians abducted on the pretext of supposed crimes].”

Both the government security forces and the separatist rebels are accused of killing civilians, sexual violence, and torture – violence that has forced more than 640,000 people from their homes. A splintering of the secessionist movement, with rival leaders either abroad or in prison, means local commanders enjoy considerable autonomy and impunity.

Does demobilisation work?

In November 2018, President Paul Biya issued a decree creating the National Committee for Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (NCDDR) for former anglophone separatist fighters, and for ex-Boko Haram fighters in the Far North region.

DDRCs were set up not long afterwards in Buea and in Bamenda, the main city in the Northwest region – part of a new government strategy to build what was touted as “peace and unity”. However, residents of the centres, who must stay there indefinitely, quickly grew frustrated, citing poor living conditions and a lack of training opportunities.

And there has been a more fundamental criticism: The demobilisation strategy has had little impact on slowing the conflict – a key yardstick. “The Bamenda and Buea centres have less than 500 residents combined,” said Arrey Elvis Ntui, a senior analyst with the International Crisis Group. “Meanwhile, deadly attacks against the army have intensified.”

Initially, anglophone communities “believed it could help as part of a package of [peace] measures in the pipeline”, Ntui told The New Humanitarian. “But fewer community leaders are referring their people there now.” They are concerned about the duration of the programme, “the intensifying conflict”, and allegations that some supposedly repentant fighters have subsequently become involved in banditry, he added.

The New Humanitarian received no comment when it reached out to the Cameroonian government with questions about the centres and the demobilisation programme.

Getting out

Ngah’s decision to quit was the relatively easy part. He then had to get to the DDRC from his separatist camp in the village of Kwakwa, about 90 kilometres north of Buea. For that, he needed to find intermediaries to link him to the authorities, and ease his journey.

He reached out to a pastor in the Kwakwa area who helped him escape to a church. From there, the government needed to be alerted about his intentions, so he was taken to meet a senior regional administrative official. The next step was a visit to the nearby gendarmerie, where Ngah’s statement was taken, and a short investigation was held to determine if he was genuine about quitting. Only then was he sent to the centre in Buea.

Like other ex-combatants, Ngah had heard the government’s promises of a fresh start and hoped to learn a trade at the Buea centre. But the reality has been frustrating delays, he said. Although the men in the programme are free to move around the city – and some have found odd jobs – the centres are not yet properly equipped to provide the long-term skills training that had lured them in from the bush.

“I came here because the government promised us a better life,” said Ngah. “I was hoping to learn a trade and get some support to start up a business of my own.” Two years later, he’s still waiting. “And even more disturbing,” he added, “I don’t know when I will leave.”

Broken promises

Fighters, many of whom had missed critical years of schooling, were encouraged to surrender and take advantage of skills programmes – from computer training to poultry farming and tailoring. The idea was that they would then graduate as young entrepreneurs, capable of starting businesses on their own.

Job prospects are extremely bleak for most ex-combatants, and skills training would give them a leg up. “The national economy – especially in the conflict regions – is floundering, so there aren’t jobs available for these former fighters,” explained Chris Fomunyoh, regional director at the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs think tank.

Hundreds of young men like Ngah took up the government’s demobilisation offer when it was first made in 2018. But a year later, ex-combatants in the centres in Buea and Bamenda began to complain about the poor living conditions, the lack of training opportunities, and uncertainty about when they could leave.

Frustrations boiled over: There were protests in Buea in January 2021, and again in February and March. Residents of the centre in Bamenda followed suit, with the ex-combatants there also urging the government to fulfil the commitments it had made.

Moses – DDRC Buea

“If the government wants the boys to come out [of the bush] peacefully, they should reorganise the integration strategy. If you are coming from the bush, you should know that ‘I am coming to be here for one month, two months, then I will be reintegrated’, rather than coming and [just being dumped] here.

“We at the centre have been making so many calls to try to help some of our brothers in the bush, but they challenge us. They say that ‘If all is well, what are you still doing at the centre?’ We are appealing to the government that this [DDR] is a way to stop the struggle. We know most of the boys are tired. But some are doubting Thomases – they need to see something concrete [from the government].

“They made us believe that our stay here was going to be for six to seven months… But I’m not regretting coming because I’m alive. When there is life, there is hope.”

Fomunyoh thinks the programme is back-to-front: Demobilisation, he suggested, should come at the end of a formal peace process, “when communities and the country are in a state of recovery, reconciliation, and reconstruction”. While lives may have been saved by some fighters giving up their guns, the overall programme “looks like a futile exercise for now”, he added.

The go-betweens

Ngah still believes he made the right decision in surrendering. “At least I’m alive,” he said. “I could have long been dead, like most of my friends who stayed behind.” He has been in contact with other fighters. They were initially keen to quit but eventually demurred due to uncertainty around life at the centre, and fear of being labelled a so-called “black leg” – a “traitor” – by their comrades, and possibly killed.

Elie Smith, secretary-general of the All-Anglophone General Conference (AGC) – a network of religious organisations – has been instrumental in helping ex-fighters leave the battlefield. “When a fighter wants to surrender, he or she secretly reaches out to a pastor, an imam, a priest, or any other religious authority in the area for guidance,” he told The New Humanitarian.

Of those who do make it out, only a few opt to enter the DDRCs, said Smith. The majority prefer to relocate to other parts of the country, searching for better opportunities or a more anonymous life. There is no clear idea on numbers of those who have quit clandestinely.

Helping the fighters is a risk. Smith and his team are branded as traitors by the secessionist movement and have received death threats. The late Cardinal Christian Tumi, one of the co-founders of the AGC – and a vocal supporter of dialogue to end the war – was kidnapped for 24 hours by separatist fighters in 2020 before being released.

Hurdles to going home

Ngah knows that when he eventually leaves the Buea centre, he won’t immediately be able to return to his home in the Ndian Division of the Southwest region. Reconciling ex-fighters with their former communities remains an uphill task for the government’s demobilisation programme.

“Some of these armed men committed [atrocities], often abusing the same communities that supported them,” said Ntui. “There would have to be proper programmes to address not only [the ex-fighters], but the large number of civilian victims who need healing after experiencing conflict crimes first hand.”

Timothy – DDRC Buea

Even for people who support the broad goals of the secessionist movement, the policy of rebel-ordered school boycotts – which have kept more than 700,000 children from attending classes – has been particularly contentious. Teachers and students defying the ban have been assaulted, and on occasions killed.

Still, Timothy, for one, felt able to justify the approach.

“When we were in the bush, they said we should stop people going to school. They made us think it was important [to shut down schools]. I was also jealous of my friends when they came back on holidays… The General [his commander] told us that they are there schooling while we are here fighting. He said that when school is going on, the world is thinking that there is no crisis, that there is no war in the country.

“Our hatred for teachers is because they were the ones teaching the students, and they are mature enough to [understand our struggle]. So when we said ‘We don’t want school’, we knew that when the teachers come, the students will come, and when the teachers [are too afraid] the students will not come.”

Despite hefty criticisms of the demobilisation programme, the government remains wedded to it, as a viable hearts and minds approach to preserving the country’s “sacred union”, while the stick of military measures is simultaneously wielded. In April 2021, a new “ultra-modern” centre in Bafut, in the Northwest, was opened. That will be followed by brand new facilities in Misselele, in the Southwest, and Mémé, in the Far North.

All ex-fighters will eventually be moved to the new sites, and Ngah and his comrades are excited about the prospect. “We’ve been told we’ll have comfortable dormitories [in Misselele] and standard workshops to learn trades of all types,” he said.

“I will finally be able to undergo my training in poultry, so that upon graduation I can fulfil my dream of becoming a poultry farmer.”

*The names of all ex-fighters have been changed as a security precaution.

Edited by Helen Morgan.