The warm welcome extended by the European Union to the nearly four million Ukrainians who have fled since the Russian invasion began in late February is putting a fresh spotlight on the bloc’s harsh treatment of people from other parts of the world who arrive to seek protection and opportunity. Among them are a growing number of Cubans who – hoping to avoid restrictive US migration policies – have been trying to reach Europe in recent years.

Like thousands of others, Castillo*, 30, who worked as an anaesthetist in Havana, left the Caribbean island nation to escape worsening economic stagnation and political repression. The vast majority of Cubans who undertake similar journeys head to the United States, which is around 150 kilometres away by sea. But hardening migration policies have made reaching the US more difficult and dangerous, and the prospect of eventually finding stability less certain.

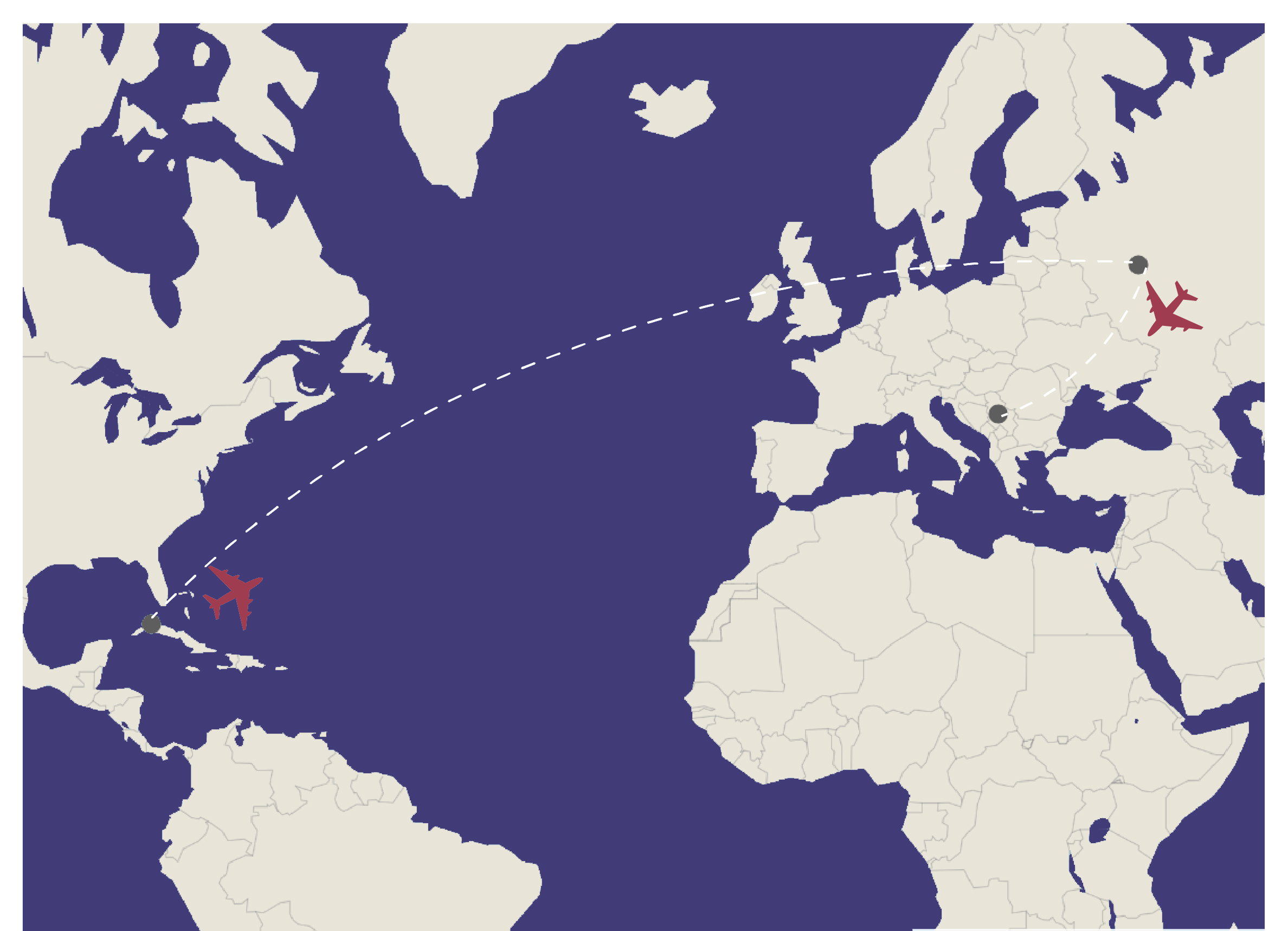

As a result, some Cubans are taking longer and more circuitous routes to try to reach countries where they hope they will receive a warmer welcome. For Castillo, this meant flying nearly 10,000 kilometres to Russia – one of the few countries where Cubans are able to travel without applying for a visa – and then taking a second flight to Serbia before trekking across North Macedonia to reach Greece.

Once in the EU, Castillo planned to continue on to Spain, but his journey took an unexpected turn. The day he irregularly entered Greece, Castillo and three other Cubans he was travelling with were detained by Greek police in the northern city of Thessaloniki and sent to a military warehouse. Inside the facility, there were already around 30 other Cubans, Syrians, Pakistanis, and Afghans.

“I could not have imagined that I would arrive in Europe only to be kicked out days later.”

Despite asking to apply for asylum, Castillo, along with the other men, was stripped naked and beaten with plastic oars before being forced at gunpoint to cross the Evros river, which runs along much of Greece’s border with neighbouring Turkey.

“The officers laughed at us when we told them we wanted to request asylum,” Castillo, who is now in Istanbul, told The New Humanitarian. “I didn’t expect any of this. When I left Cuba, I could not have imagined that I would arrive in Europe only to be kicked out days later to a country I had never been to.”

Greece — one of the main entry points to the EU for people from the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa — has introduced a sweeping series of hardline policies in recent years. Those include a dramatic expansion of the expulsion of asylum seekers and migrants without allowing them to claim protection.

Greek security forces have carried out expulsions at the Evros border for decades, but the practice – known as pushbacks, and which is illegal under international law – has increased significantly in the past two years, with potentially tens of thousands being pushed back from Greece’s land and sea borders.

The expulsions have also been taking place from deep within Greek territory, a tactic that began in 2020, according to Hope Barker, a policy analyst at the Border Violence Monitoring Network, a coalition of NGOs that documents human rights violations at the EU’s external borders.

“The Covid-19 pandemic made it easier for the Greek state to further demonise people on the move, presenting them not just as threats to security, but also to public health,” Barker told The New Humanitarian.

The vast majority of those who have been expelled are asylum seekers and migrants from the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa trying to enter the EU from Turkey. In that sense, Cubans like Castillo are an anomaly, but the fact that their attempt to circumvent hardline migration policies in the US ended with their expulsions from Greece highlights the proliferation of harsh migration policies that have made it more difficult for people to seek refuge in both North America and Europe in recent years.

The expulsion of Cubans to Turkey also adds a new and troubling wrinkle to the Greek pushbacks, according to Natalie Gruber, founder of Josoor, an NGO that monitors pushbacks at the Greek-Turkish border. “They had never set foot [in Turkey] before,” Gruber said.

Despite widespread documentation by human rights groups and journalists, the Greek government denies that pushbacks are taking place. A recent government investigation found “no documentary evidence” that the informal forced returns were being carried out.

Economic struggles and political repression

Migration from Cuba has ebbed and flowed with political and economic developments for decades. Most recently, the combined effects of renewed US sanctions and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have thrust the country into its worst economic crisis since the 1990s. Cuba’s economy shrank by 11 percent in 2020, inflation reached 70 percent in 2021, and shortages of food and medicine have been widespread.

“Everybody is affected by these shortages no matter what your profession,” Castillo said. Working in the medical profession did not insulate him from the crisis. “We had to work long shifts in ill-equipped hospitals for $52 a month. I could barely afford to buy food for myself,” he added.

Frustration over the situation led to the largest anti-government protests in decades last July, which Cuba’s communist government quashed with a wave of severe political repression. More than 1,000 people were arrested, and lengthy prison sentences – ranging from six to 30 years – were recently handed down to more than 100 people who took part in the demonstrations.

“It has become increasingly difficult for Cubans to receive asylum or be admitted as immigrants in the US.”

Cuba’s economic struggles and the fresh wave of repression have spurred a sharp increase in emigration from the country. Most who leave still try to reach the United States. For decades, the US granted most Cubans who set foot in the country permanent residency as part of its adversarial stance towards Cuba’s communist government. But in 2017, as part of a move toward normalising relations with Cuba, the Obama administration ended that policy.

Since then, “it has become increasingly difficult for Cubans to receive asylum or be admitted as immigrants in the US,” Jorge Duany, director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University, told The New Humanitarian.

In 2018, when the Trump administration introduced the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the “remain in Mexico” policy, Cubans were among the nationalities included in the programme. MPP required them to wait in Mexico – often in unsafe conditions – for the duration of their asylum processes. And since March 2020, access to international protection at the US southern border has been severely restricted under Title 42, a heavily criticised pandemic-related public health order that allows anyone who enters the US irregularly to be immediately expelled without being able to ask for asylum.

Despite these barriers, the deteriorating conditions in Cuba have led to an increase in Cubans trying to enter the US. The number of US Border Patrol apprehensions involving Cubans jumped from around 9,800 in fiscal year 2020 (which runs November through October) to more than 38,000 in fiscal year 2021. As the US has put pressure on Mexico and Central American governments to crack down on migration, Cubans have resorted to taking longer, more dangerous routes to try to reach their destinations – such as trekking across the infamous Darién gap that connects Colombia and Panama.

‘I am stuck’

As an alternative to the US, some Cubans have started looking toward the EU, and particularly Spain, which has been the second most common destination for Cuban asylum seekers and migrants for a number of years.

For those who could not secure a visa to travel to the EU, the flight to Russia, with its visa- free entry for Cubans, proved one of the most accessible first steps. From there, Cubans have tried to enter the EU in different ways, including by crossing the Polish-Belarusian border – where a political showdown last year led to a sharp increase in migration and humanitarian needs – and by floating down a river from Russia on air mattresses to try to enter EU member state Estonia.

But until recently, the route to Serbia and then Greece was the most common. International sanctions and airspace bans on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine have since made travel from Cuba to Moscow more complicated. “Since the Ukraine war started, I have not heard of any more Cubans coming to Russia,” said Castillo. “Actually, many Cubans already in Russia are now trying to reach Europe via Belarus.”

“I cannot go back to Cuba because I would be punished for leaving, but I also cannot live here illegally.”

Alvaro*, a 26-year-old who used to work for Cuba’s National Office of Tax Administration, told The New Humanitarian that before the war, Cuban friends who had already travelled the Russia route explained “that if I went to Russia, I would then be able to get in touch with smugglers who organise your trip to Spain through Greece. We would have received more information from the smugglers once we arrived in Athens, but we never made it there.”

Alvaro, like Castillo, was expelled from Greece to Turkey shortly after entering the country in October last year. They are now part of a growing community of Cubans who have ended up in Istanbul after being pushed out of Greece. “There are well over a hundred of us Cubans in Turkey,” Castillo estimated. “I am stuck. I cannot go back to Cuba because I would be punished for leaving, but I also cannot live here illegally in a country that I never chose to come to.”

Attitudes towards refugees and asylum seekers have also soured in Turkey in recent years. The country hosts around four million refugees – the largest refugee population in the world. Around 3.6 million are from neighbouring Syria and have been in the country, in some cases, for 10 years. Like Cuba, Turkey is in the midst of a severe economic crisis, and waning enthusiasm for hosting refugees has turned into outright hostility. That has manifested in protests, attacks against Syrians, and the Turkish government coercing some Syrians to return to Syria – despite human rights groups arguing that the country is still unsafe.

It is not an easy setting for a comparatively small number of Cubans who never intended to be there to get their footing. Turkey only grants international protection to asylum seekers from non-European countries on an ad hoc basis, and, so far, it does not have a specific policy for managing the Cubans

Alvaro said he reported his pushback to the Turkish police. “Instead of providing any help, they issued a deportation order and made me sign a two-year restriction to enter Turkey,” he told The New Humanitarian. Three other Cuban nationals who are in the same situation as Alvaro confirmed that they had also received deportation orders when they reported their pushbacks to police.

Alvaro and the other Cubans are undocumented after Greek authorities took their passports. The risk of destitution and deportation is an anxiety that adds to the trauma of the pushbacks. “It is very difficult to have a place to stay, because nobody rents to you if you are undocumented, and to pay the rent is also hard,” said Castillo.

Cubans in Castillo’s and Alvaro’s situation have little choice but to find informal work in factories or restaurants, often for less than $2 an hour. “My first job was washing dishes for 3,000 Turkish Lira [about $200] a month,” Alvaro said. “But my family and partner also sent me money. I wouldn’t survive here without their support.”

As Castillo explained: “I was hoping to have some kind of respect and protection within Europe. But it turned out to be the most dangerous place I have ever been.”

*Castillo and Alvaro are pseudonyms used to protect the identities of the people interviewed for this piece.

Edited by Eric Reidy