A confrontation is brewing in rural Italy over who should get to determine the needs of the most marginalised among the approximately 550,000 foreigners – including 150,000 undocumented migrants – working in the country’s key agricultural sector.

Growing tensions between aid workers and union organisers in the Apulia region highlight the divide over whether poor living conditions in dozens of informal settlements across the country should be viewed as part of Italy’s so-called “migration emergency” or as the product of rampant labour exploitation in a highly profitable industry.

On one side, aid workers and local officials say the informal settlements housing the migrant workers should be brought under institutional control. Dismal conditions in the settlements – where running water is often scarce and improvised electrical lines sometimes spark fires – have led to over 1,500 deaths since 2014, according to one estimate.

“It is necessary to have a third sector entity to best organise and direct the daily life in these communities,” Roberto Venneri, head of the Apulia government department tasked with dealing with migrant settlements, told The New Humanitarian.

Union organisers, on the other hand, say the migrant workers don’t need aid; they need a long-term solution, and the approach advocated for by local officials and aid groups is not it. They argue that Italy needs to address racism and the exploitation of migrants in its agricultural sector, and provide an effective pathway for the undocumented to regularise their status.

An amnesty law passed in May to address economic and public health concerns stemming from the coronavirus pandemic paved the way for more than 207,000 people to apply for six-month residency permits, but only 15 percent of applications came from agricultural workers.

The situation in Apulia boiled over mid-June when a group of aid workers set out on a routine visit to Torretta Antonacci, one of the largest informal settlements in Italy, also known as the Gran Ghetto.

The settlement is home to somewhere between 800 and 1,000 people depending on the season. Aid workers had been providing services there since the beginning of Italy’s coronavirus lockdown in March, but on this day found the road into the shanty town blocked by a picket line organised by a grassroots Italian labour union, the Unione Sindacale di Base, or USB.

Forced to retreat, the aid workers called on the police to take action against the union organisers, who they said instigated the protest.

A growing problem

Informal agricultural settlements have proliferated around Italy’s farmlands since at least the 1990s. But they have grown in number and size since migration to Italy across the Mediterranean spiked between 2014 and 2017.

Many who arrived during those years moved on to northern Europe. But others, particularly people from sub-Saharan Africa, stayed. Some ended up in legal limbo waiting for their asylum claims to be processed, or were stripped of humanitarian protections by security decrees passed in 2018. With little option but to work in the informal economy, many ended up in the settlements.

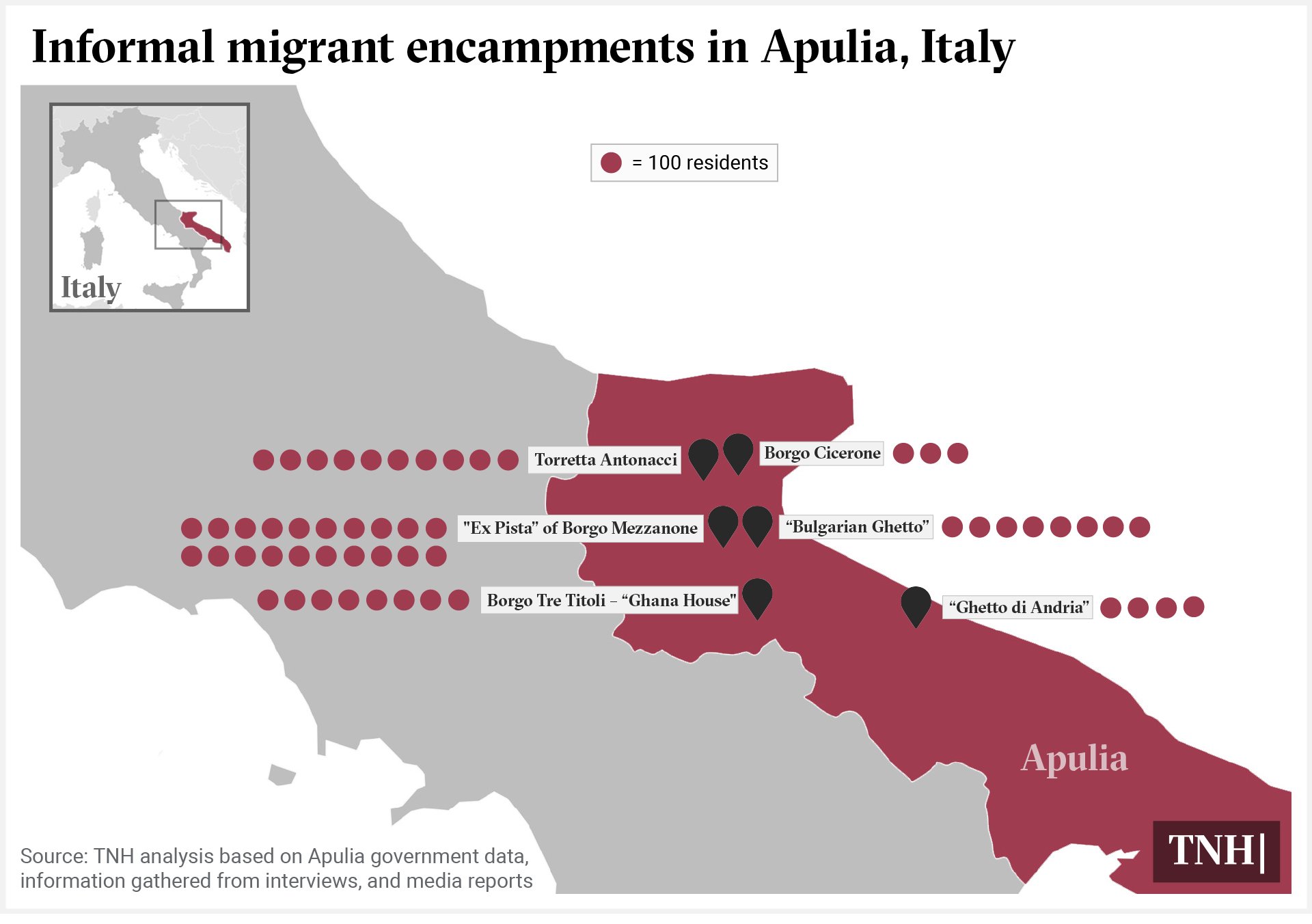

There are eight settlements in Apulia alone, hosting between 400 and 2,000 people each, according to regional government estimates. Stereotyped as hotbeds of criminal activity, the biggest actually take the form of robust, small communities: There are restaurants, shops, even nightclubs in some, and migrants living in nearby cities visit on the weekends to spend time in places that feel removed from the stigmas often attached to African migrants in Italy, according to migrants interviewed by TNH.

To find work, many residents have to rely on the caporalato system, a 17-billion-euro-a-year industry of illegal employment. Working conditions and pay vary, but migrant labourers who spoke to TNH say they are often required to work for up to 12 hours and can earn as little as 30 euros per day. Italy has laws prohibiting the practices the caporalato system relies on, but they are routinely unenforced.

In Apulia, the agricultural sector is estimated to be worth 3.6 billion euros, and it was assigned an additional 1.6 billion euros in farm subsidies and other agricultural funding from the EU between 2014 and 2020.

Union organisers want some of that money to go towards improving the treatment or living conditions of the people working in the multi-billion-euro industry.

“This place is a gold mine, but its profits don’t benefit us.”

Instead, help to improve the living conditions of agricultural workers comes from EU and Italian migration funds, and the Italian government leans on aid groups to oversee the projects it implements, according to Venneri, the Apulia government official.

“This place is a gold mine, but its profits don’t benefit us,” Aboubakar Soumahoro, a high-profile union organiser originally from Ivory Coast who has become a national symbol of the resistance to these policies, told TNH in 2017. “Subsidies [to farmers] should at least be tied to the respect of employment contracts… They want to force us into the dependency industry, where money goes to enrich aid cooperatives and not to benefit us.”

‘Troublemakers’ in the ghetto

Last December, a fire ripped through Torretta Antonacci, burning many makeshift shelters to the ground. In its wake, regional authorities installed 106 shipping containers as emergency housing, and issued a call for aid groups to use a new large tent they had pitched in the settlement for humanitarian projects.

“To this call, we responded: ‘we are in’,” Domenico La Marca, director of Baobab Experience, an Italian NGO, told TNH.

Baobab Experience has been providing legal advice and help accessing healthcare to migrants in the nearby town of Foggia for more than 10 years. La Marca saw the opening of a humanitarian centre in Torretta Antonacci as an opportunity to expand the group’s activities in a location where they were sorely needed.

Baobab Experience was joined by the local chapter of the Catholic charity Caritas and a labour union called FLAI-CGIL, which advocates for the removal of informal settlements and the provision of alternative housing.

The three groups started making weekly trips to Torretta Antonacci to teach Italian classes, provide legal and health assistance, and run leisure activities like football matches or games of draughts (checkers).

“Since our first visit – when 30 people signed up for our Italian classes – I was approached by some people tied to USB,” La Marca said. “They told me very clearly that they are not children, that they didn’t need us, and they invited us to collect our toys… and go away.”

La Marca said tensions escalated week by week until the picket line in June, and claimed the USB organisers were pressuring people to participate. “[They] were inciting these poor boys, who didn’t believe, themselves, in what they were doing, screaming ‘libertà’ [‘freedom’]. Some couldn’t even pronounce it properly,” he said.

‘We are all equals here’

In July, when TNH visited Torretta Antonacci, a police car was parked at the far end of the dirt road leading to the settlement, “a form of long-distance policing, to ensure the safety of aid workers,” the officers said.

Workers were returning from the fields, and the shops, grocery stores, and informal night clubs in the makeshift part of the encampment that survived the fire were busy with clients. One of the containers in the new section was draped in USB flags.

“Why do they have to keep coming when we no longer need help? We are all grown-ups here; people who work hard to take care of their families.”

Inside, Sambaré, a USB organiser who is originally from Mali, was blunt. “We organised a roadblock, and we stand by what we did,” he said. “When Caritas brought us food during the coronavirus [lockdown], we were grateful for that. But why do they have to keep coming when we no longer need help? We are all grown-ups here; people who work hard to take care of their families.”

When local authorities installed the containers, union organisers initially celebrated it as a victory, or at least as an acceptance of their right to stay – in the past, the regional government had taken an antagonistic stance towards the settlement, even bulldozing it in 2017.

But now Sambaré fears the installation of the containers, and the aid projects that came along with them, might be the first step towards turning the informal settlement into a government-administered camp.

When this has happened elsewhere, local authorities have hired private security companies to control access to the sites by checking residency documents, which forces people without legal status out. Government control also means aid groups provide food and other supplies, which can choke off the informal economy, an important source of income for inhabitants.

“This space needs to remain self-managed,” Sambaré said. “We won’t accept any distinction based on who has documents and who doesn’t. We are all equals here.”

But local officials and aid groups reject the idea. “We are not looking for police control… [but] it is unthinkable to go down a path of self-management,” Venneri said, adding that it’s essential for aid groups to manage the settlements, and that EU funding isn’t used to host undocumented people, who he referred to as illegals.

After the bulldozing of Torretta Antonacci in 2017, most residents refused to move into government-sponsored housing because they didn’t want to give up their personal autonomy. “I also would like to live comfortably, to take a hot shower, but at least here nobody rules over you,” Galoume Madourie, a long-term resident of Torretta Antonacci, told TNH at the time.

‘The will to speak for themselves’

For now, the aid groups have resumed their weekly visits to Torretta Antonacci. And as long as the response to the living conditions in the informal settlements is being viewed by officials – and funded – as part of the migration crisis, their approach will likely win out.

But Soumahoro isn’t backing down. After resigning from the USB in July, he launched a new union, the “Lega dei Braccianti”, specifically focused on organising agricultural labourers.

The group is headquartered in another shanty town in Apulia, and organisers like Sambaré have followed Soumahoro into it. They are aiming to build a coalition to push for an immigration amnesty that will benefit agricultural workers and address the marginalisation of migrants, not through aid but through structural change.

When Soumahoro announced his new initiative, he stressed the importance of self-representation. The struggle for the rights of the invisible, he wrote, “must be accompanied by the will to take the floor and speak for themselves”.

lda/er/ag