UK Development Secretary Penny Mordaunt has probably had better days. As the host of the 18 October London conference on steps to address sexual abuse in the aid sector, she went for a bumpy ride: a prominent activist conspicuously boycotted the event; a whistleblower interrupted Mordaunt’s keynote address, walking on stage and charging that victims were not being heard; and the agenda, speaker list, and planning process all came under heavy fire in private and across social media. On top of all that, critics charged that the event was elitist and white-dominated.

Before the UK-hosted international Safeguarding Summit 2018 even began, the flagship initiative for which the conference had been intended to serve as a launching pad had already come under sharp criticism. A preview of a £10 million government scheme to work with Interpol to vet aid workers against criminal records met with dismay from development sector analysts when it was announced the day before. Most often, those critics charged, even serious cases of misconduct do not end in a criminal conviction.

Commonly, the person is sacked or resigns, and the employer’s investigations may be inconclusive and prosecution difficult in third countries. What that means, several aid workers noted, is that any database of convicted criminals won’t catch predators.

“The list of bad guys will be very short,” one senior aid worker said. Another NGO official said the majority of cases aren’t even reported, so there would be no trail to follow. A spokesperson for Save the Children said the project was not a “silver bullet” but hoped to use Interpol “green notices”, which can provide alerts without necessarily requiring a conviction.

An overnight press release caused further dismay: Mordaunt announced a “coordinating” role in the vetting project – dubbed “Soteria” – for the NGO Save the Children. Several observers were surprised, others outraged: Save the Children UK is currently under investigation by UK authorities for its handling of sexual misconduct in 2015, both by its former CEO and a former senior manager. Whistleblowers have said there was a coverup, and the NGO admitted spending over £100,000 in legal fees this year to steer media reporting of the story. To award them funding in a new preventative structure “spits in the face of survivors," one experienced aid worker said.

A spokesperson for UK Department for International Development told IRIN that Save’s role in the project does not involve DFID funding. When pressed on the suitability of involving Save, the spokesperson said that the organisation’s “expertise in dealing with these cases” and “commitment to tackling this issue” in fact made it particularly suitable for a role on the advisory board of the project.

When told of that explanation, a senior aid worker who attended the conference sent IRIN a one-word message: “Bahahahaha”.

A spokesperson for Save explained that the NGO’s head of safeguarding, Steve Reeves, had conceived the idea for the vetting system and in 2016 had approached Interpol, which will participate in the vetting process. When viewed in that way, the spokesperson said, DFID was joining an existing initiative, supplying “money and leadership”.

Red flags

The event had been intended to highlight the UK’s attempts to drive efforts to address sexual exploitation, harassment, and abuse in the international aid sector. The issue leapt onto the international agenda after revelations about sexual misconduct by a senior Oxfam staff member were published in the London Times.

Then, #MeToo and, later, #AidToo scandals and revelations snowballed, rocking public confidence and the reputations of NGOs. Media and public investigations revealed that vulnerable women, possibly under-18, had been blackmailed for sex by aid workers and public outrage greeted news of the widespread use of sex workers by expatriates in the field. The litany of cases included accounts of workplace rape, assault, and harassment that were seen to be badly handled or had been denied or covered up.

Even in the runup to the conference, red flags were raised, according to several senior aid workers (most of them female) who monitored the planning and attended or followed the conference online. They, in messages with IRIN, pointed to criticisms that ranged from not allowing enough time for audience questions to a lack of diversity among speakers.

The confirmed agenda and speaker list was circulated only 48 hours before the event. An attendee noted that “inclusion is such a problem still,” pointing to “a lack of brown/black/southern voices”.

It was with a sense of “despair”, survivor and activist Megan Nobert noted in her address, that she felt the community needed to be reminded “that the voices and lives of those impacted people” should be at the forefront. “It is easy,” she said, “to get caught up in the technical aspects of safeguarding… redrafting policies, trainings, hotlines, worrying about the media and... funding”.

In an open letter, activist Paula Donovan declined to participate, calling the event “cavalier and offensive”. Donovan heads “Code Blue”, a campaign calling for the UN to crack down on sexual abuse amongst its staff and peacekeepers. Donovan claimed the agenda consisted of too many “powerful institutions’ appointed spokespersons”. The pain and suffering of survivors, she wrote, “should never be exploited by powerful institutions for public relations or damage control purposes”.

Criticisms and commitments

“It seems more about DFID and its public profile than real measures to address this long-standing problem,” one senior aid worker said, referring to the UK Department for International Development. The worker, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the issue, added that too little attention was paid to abuses in the field.

At the event, the audience of several hundred people who ranged from victims to government officials, heard from survivors, whistleblowers and activists and listened as a range of institutional and government commitments were made. In her remarks, Mordaunt called for “clear, ambitious commitments” and “coordinated global action” to combat sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment in the aid sector. She said Britain and other large donors would address four main areas: preventing abuses, listening to survivors, responding “decisively”, and learning to do better.

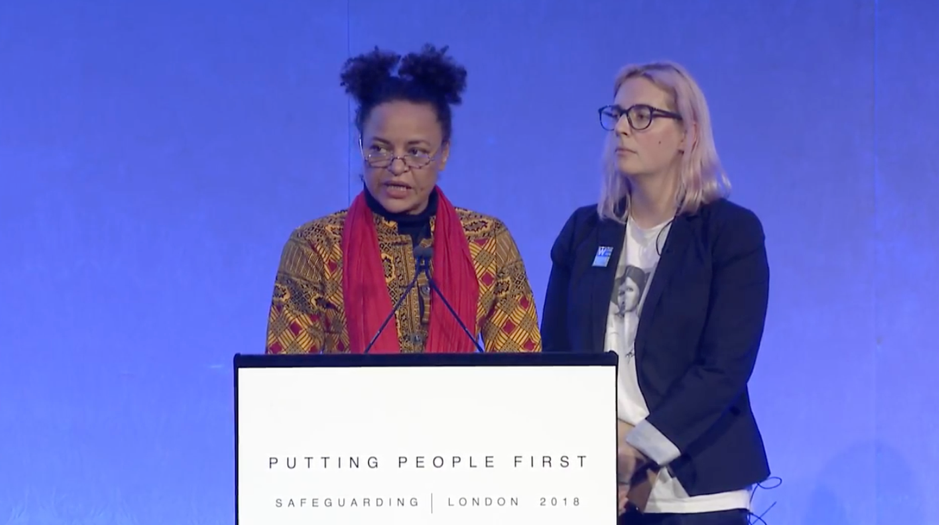

As Mordaunt spoke, a former Save the Children employee, Alexia Pepper de Caires, slipped onto the stage and interrupted with her own brief speech. De Caires said she was “disgusted” that Save the Children were selected for a new safeguarding role. De Caires has campaigned for the organisation’s CEO and board members to take more responsibility over its earlier failings. She said women who had worked on the issues “for decades” had been sidelined. “We do not need fancy new systems,” she noted. “We do not need technology, we need systematic change” and to understand issues of “sexism, racism, and abuse of power.”

In response, Mordaunt gave up a later speaking slot to de Caires and other whistleblowers and survivors; former Oxfam employee Lesley Agams; and former UN employee Caroline Hunt-Matthes.

In addition to the vetting system, several other initiatives were announced at the conference. They included a collective reference-checking system intended to prevent staff from circulating from one agency to another without their misconduct catching up with them. The effort, currently involving 15 agencies, will be coordinated by the Geneva-based aid agency consortium Steering Committee for Humanitarian Response.

The Dutch government is backing a proposed independent ombudsperson who could investigate allegations of misconduct and abuse that organisations can’t or won’t complete themselves. The next steps may be to find an institutional home for the project and define its scope before launching field-based pilot projects. Analyst Asmita Naik, author of a 2002 report on sex-for-aid in West African relief operations, said the“most pressing need“ was “somewhere for victims to make complaints and ensure these are investigated independently.”

A humanitarian passport scheme, in which accredited aid workers would be issued an ID card attesting to their clean records, has been backed by DFID and led by Save the Children, was also raised. Such a plan requires refinement on several levels, some conference attendees noted, as the legal and data protection issues are complex, as is the definition of “aid worker”.

bp/js