A months-long investigation by IRIN into the secretive intelligence-linked firm Palantir, reveals a cosying up to aid organisations large and small, including a bargain-basement contract with a sensitive UN agency, and a flirtation with the international response to the Ebola outbreak. But how close is too close?

- UN nuclear watchdog IAEA, dealing with Iran and North Korea, has contracted Palantir at rock-bottom rates

- Palantir was close to a role in the UN's Ebola response, but walked away

- The UN's humanitarian arm engaged Palantir on a proof-of-concept analysis in the Philippines

- The Silicon Valley "unicorn" explored the non-profit sector as hedge against a decline in counter-terrorism opportunities

- Political and confidentiality concerns limit its success, as well as a clash of organisational cultures

The software is amazing. It’s an all-powerful data integrator: combing through data from documents, websites, social media and databases, turning that information into people, places, events, things, displaying those connections on your computer screen, and allowing you to probe and analyse the links between them.

The tool, developed by secretive Silicon Valley firm Palantir, can be enlisted to tackle a range of humanitarian problems: from people trafficking and gun-running to stemming floods. It could revolutionise disaster coordination, management and response.

But the global aid community is wary. Palantir retains extremely close links to the US security establishment, and the line between politics and humanitarian work is under constant attack and incrementally being pushed back.

After a months-long investigation, IRIN can reveal how potential aid partners are spooked by these political and security connections and how a major deal with a key UN agency recently fell through because of them.

The power of Palantir’s pattern-finding data analysis is already used by blue chip US humanitarian organisations including the Carter Center, the Clinton Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation and the dirty-money chasing arm of the George Clooney-affiliated Enough Project.

“It’s a transformative tool,” said Andrew Brenner, of the Rockefeller-linked 100 Resilient Cities Initiative. “Palantir’s engagement in Norfolk (a flood-prone city in Virginia) has completely changed the way the city goes about its planning work and its response efforts; and that’s no small feat, to change the way a city operates.”

But the data analysis software has other, less benign applications. Palantir, whose initial investors included the CIA’s venture capital outfit In-Q-Tel, is in tight with the US security services – so tight in fact that the private Palo Alto-based firm is widely rumoured to have been behind the tracking and finding of Osama Bin Laden.

The UN’s nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency, has also hired Palantir. The challenge for the IAEA is the verification of non-proliferation agreements – Iran and North Korea for example – and it spent $500,000 in 2014 on Palantir's Gotham software to analyse the available data.

“The idea that the likes of Google, GPS, Microsoft don’t have ties with US intelligence is silly”

It seems to fly in the face of humanitarian principle, let alone common sense, for aid workers to seek to partner with an outfit that has its roots so firmly embedded in covert operations.

There are many places in the world where a Palantir logo on your laptop would not be the wisest bit of branding. And there’s the related, almost reflex, concern, that having Palantir in the room is an open invitation to the US National Security Agency to read your email and add your data to their vast, global, intelligence trawl.

But Andrew Schroeder, director of research and analysis at the US humanitarian outfit Direct Relief, an early philanthropic partner for Palantir, dismisses fears that working with the firm means compromising your data and opening a backdoor to Langley, Virginia.

“Palantir is hardly the only software company that has security links. The idea that the likes of Google, GPS, Microsoft don’t have ties with US intelligence is silly, ” said Schroeder, who worked with Palantir in the Philippines when the firm provided data analysis for a Direct Relief health project.

“I always assume that if they want your data, they will find a way to get it. Humanitarians are not good at data security even on a good day,” he noted. “But I don’t see any benefit for the intelligence community to find out about Direct Relief’s medical aid shipments. They can find that on our website.”

But humanitarian advisor Paul Currion has more fundamental concerns.

“Technology is often viewed as neutral, and it’s marketed to us like that. But the reality is that when it comes to software, there are assumptions built into code,” he said.

“The assumptions of the intelligence community are not the same as our assumptions. Software designed based on their assumptions will not necessarily serve our purposes, even if the tools themselves might be useful.”

His objection to working with an organisation like Palantir is essentially political. “The question is whether humanitarian organisations should share our broader political concerns. I would argue strongly yes – that humanitarian principles actually should translate into a concern about military-industrial surveillance and its providers.”

Human rights and technology researcher Tom Longley references a 2011 scandal in which a Palantir engineer was involved in plans to launch cyberattacks on WikiLeaks. He was suspended, but then reappointed. “I’m curious,” wrote Longley in an email exchange. “What would it take for Palantir to become an unacceptable ally?”

Sanjana Hattotuwa, a senior researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives and special advisor to the ICT4Peace Foundation, believes that no one can be under any illusion in this post-Edward Snowden world: “If you’re concerned about security, you shouldn’t be on the internet”.

“My opinion on Palantir is that they provide a service that is perceived to be valuable,” he said. If they were ever found out “to have deep links with spook infrastructure”, they would be “finished as a company, and so it is in their interest to actually mean what they say”.

“I don’t think they hide what they are,” explained a director of a Geneva-based non-profit whose team analyses data on crises from open sources. “They pitch their software as the stuff you use to find bad guys.”

His keen interest is “because I don’t see any other software with that level of functionality… I want the best hammer in my hand, and that happens to be Palantir.”

And Palantir is not the only startup funded by the CIA’s venture capital firm that works in the humanitarian world. Recorded Futures, backed by In-Q-Tel and Google, monitors the web for “real-time threat analysis”. It was hired by the UN Development Programme after the Georgia/Russia conflict to scan social media for clues to upcoming crises.

Humanitarian coordination is only going to get harder. The exponential growth in data means more fragmented information, more formats, more tools, more complexity, more urgency.

“Increasingly, it’s a software problem,” said Jonathan Stambolis, previously head of international partnerships at Palantir, now founder of Zenysis Technologies. “The challenge is the streamlining of information, its cleaning, collating, managing and integrating.”

Humanitarian work, or as Palantir calls it, “philanthropy engineering”, is almost the pro bono side of the company, which is currently valued at $20 billion, making it the fourth wealthiest venture capital-backed firm in the world (Peter Thiel, one of Palantir’s founders, also has a substantial stake in accommodation service Airbnb, ranked third).

Palantir was launched in 2004. Its core business spans three broad areas: government contracts (the defence and security establishment, but also FBI and local law enforcement); the financial sector, where its software helps detect fraud; and legal research – what it calls “legal intelligence” – connecting the dots within the data, which reportedly helped in the conviction of Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff.

It makes its money from selling licenses on its groundbreaking software, which can be off the shelf or bespoke. But the real earner is in the super-smart staff it sends in to run the system for you – its “forward deployed engineers”, in Palantir’s militarised argot.

According to Richmond, a “barebones” system at commercial rates would set you back $7 million a year; bells and whistles and you’re talking $12-15 million – although the price varies hugely depending on scale and task.

Yet it provides these services to humanitarians virtually for free. In the case of proposed partnerships with the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, OCHA, and later the Accra-based UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response, Palantir offered such heavy discounts that the deals would have caused problems with the UN’s procurement procedures, officials familiar with the details told IRIN.

“Palantir philanthropy has tended to be more interested in the problem sets rather than whether people in [the aid industry] can pay for it,” said Schroeder.

“They find it to be of signature benefit to the company, from a recruiting standpoint, that their engineers will work on the world’s hardest problems, like human trafficking and disaster relief – things that are meaningful.”

“I think they underestimated how paranoid we are about the dark side”

Palantir’s initial interest in the non-profit world seemed to be more the search for a new business model than altruism. Direct Relief was one of its early partners and Schroeder describes a scenario in which, before the emergence of so-called Islamic State, counter-terrorism seemed to be on the wane, and not the same growth opportunity it is today.

“I could see us in retrospect being some kind of research project,” said Schroeder. They knew there were “paying clients” within the disaster relief sector, “we just didn’t happen to be one of them”.

Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 provided an opportunity for Palantir to show the humanitarian community what its software could do. Their pointman was Stambolis, who had been an adviser to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and knew Valerie Amos, then head of OCHA. “That was effectively how they got through the door,” said one OCHA official.

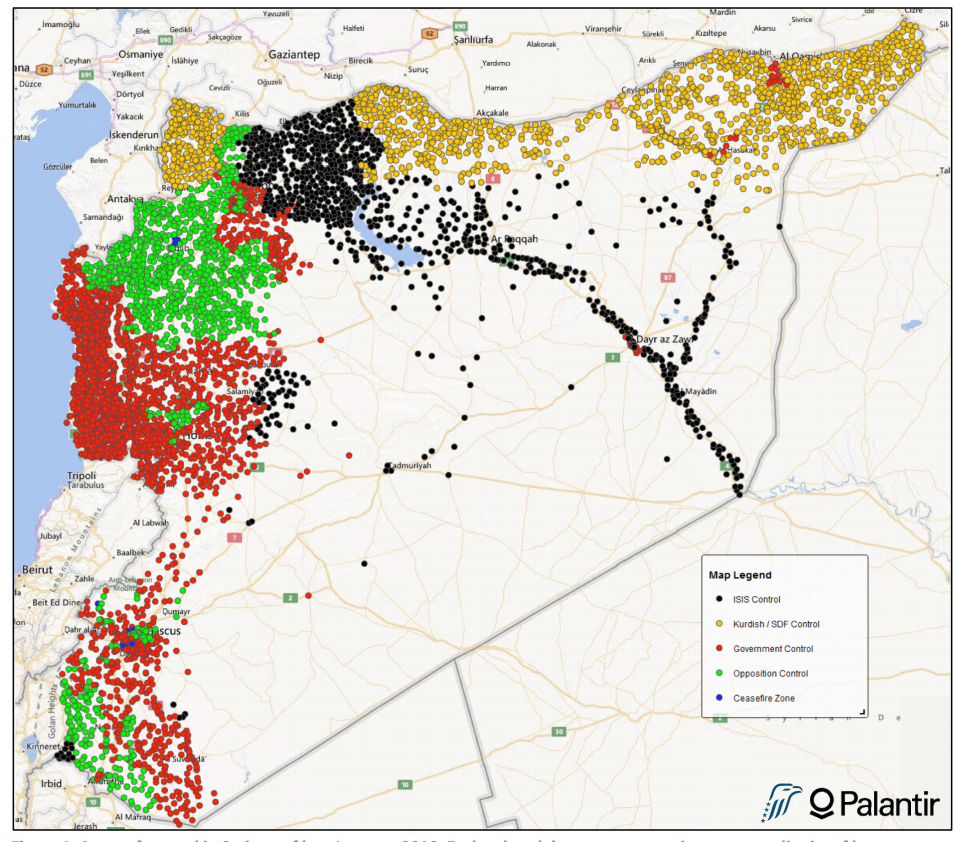

They were keen to understand the data challenges and ran a “who, what, where” service in parallel with OCHA’s. One question they were asked to explore, and were able to solve, was whether food aid deliveries were being politicised – with particular constituencies favoured. The answer was not made public by OCHA.

Athough Stambolis said he was unaware of any unease caused by Palantir’s intelligence connections, more than one OCHA staff member confirmed that it was indeed those fears that sunk the deal. “The OCHA [donor relations] people said we should be very careful & cautious about how we work with them,” one official, with years of disaster experience, wrote in an email.

“I’m sure they had the idea they could become the central information infrastructure for the humanitarian community,” said the Geneva-based humanitarian director. “If that’s the case, they’re not on the right track. I think they underestimated how paranoid we are about the dark side.”

A case in point was his request for anonymity. He has courted Palantir, and has had at least one sit-down meeting in their Washington office, but they are yet to make him an offer. “They must be busy,” he suggested.

But he didn’t want his name or that of his organisation used in this story. “If we’re known to be using that software, then our credibility goes out of the window and we’re the humanitarian black sheep.”

That concern says something about the cultural difference between US and European humanitarian traditions, as evidenced by the embrace of Palantir by the US non-profit elite. For Currion, US philanthropy is more “Wilsonian” – willing to work in partnership with government foreign policy goals – as opposed to the more “Dunantist” values of independence, impartiality and neutrality.

Richmond, a former “forward deployed” engineer, says Palantir has a more critical problem: “It doesn’t really understand the humanitarian world – the two sides don’t speak the same language”.

Palantir approaches coordination, for example, as a big logistical tasking exercise. By providing a common operating picture you can make it supremely efficient – a level of shared purpose not all humanitarians are accustomed to.

“There’s a difference between the military operations model and us,” said the Geneva-based wannabe Palantir partner. “The tactical level doesn’t exist for us. I don’t need to know where every truck is, what bridge is down. We’re much more at the strategic level – are we targeting the right district?”

Or as Richmond put it: “It’s a Ferrari, and you don’t always need a Ferrari."

Palantir's partners have included:

National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children

Palantir got much closer to striking a deal with the UN over its Ebola response – at a time when the virus was seen as the greatest threat to global health. But, on this occasion, it was the one to walk away from the table.

“You couldn’t find a greater mess in need of data integration,” said one senior source in the UN’s Department of Field Support. “But I think they got scared about the liability of putting people on the ground because of the disease. But if they didn’t put people on the ground, it would fail.”

Stambolis, who was negotiating the deal but left the company before it was due to be signed, agreed, but offered an additional point. “To have done the job well would have required a tremendous amount of focus and resources,” while the company was growing incredibly quickly in so many other, lucrative, areas.

Palantir’s lack of a singular humanitarian focus led Stambolis to form Zenysis Technologies. After two years with the company, “trying to overcome institutional barriers, I realised that to really unlock the potential [of Silicon Valley] to solve the problems we care about required the creation of a new organisation – solely dedicated to serving the global humanitarian community.”

“Over time, I think Palantir’s philanthropy model has changed,” said Schroeder. “They inherited a set of business practices from their other clients, and they were trying to figure out how to apply it to non-profits. I think what surprised them is how much they needed to change in order to fit their technology to the non-profit context.”

Palantir may have decided it doesn’t need the headache of the humanitarian world. Richmond, for one, believes the aid industry needs Palantir far more than the firm – busy gobbling up office space in Palo Alto – needs it. IRIN was unable to get a response from the company to its many questions.

Although Palantir’s growth has been staggering, it is not immune to the current market turmoil. That might make them even more selective in terms of philanthropic partners.

The Geneva-based director is still patiently waiting for his call. “I reached out to them, but they didn’t take the bait,” he said. “Maybe the story we tell doesn’t interest them.”

oa/ag/bp/ha