While you may have a bit of end-of-year time on your hands, here are a few stories our editors would hate for you to have missed, along with their thoughts on why they will still matter in 2023.

They include a Dalit journalist’s look at caste discrimination in Indian disaster response, an illustrated diary that explores how life changed in villages around Kyiv as Russian tanks rolled in, and a profile of a farmer in Mali whose peacebuilding efforts with jihadist extremists led to some unlikely victories for his community.

Reporting on Yemen's war whilst living through it

‘I will not leave my family to die here’: A photojournalist in Yemen’s Marib

When Yemeni photojournalist Nabil Alawzari spoke to The New Humanitarian from his adopted home in Marib, central Yemen, he was living extremely close to the front line of a Houthi rebel-led offensive on the city and province. He describes what it feels like to document the toll of a war at the same time as he wonders when he should take his family and run. His words are an important reminder that most of the journalists who photograph and write about wars are living through them, and they paint a vivid picture of life in a conflict zone.

Why it matters in 2023

In April, four months after this conversation with Alawzari was published, Yemen’s warring parties agreed to a ceasefire. For a while, the shelling stopped, the guns were quiet. The truce didn’t stop the violence in all of Yemen, nor did it bring the relief so many people hoped for from a crippling economic crisis that has left many struggling to buy increasingly expensive food. The ceasefire expired in October, and while this hasn’t meant a major uptick in violence, heading into 2023 there is certainly no peace after nearly eight years of war. There is also a massive need for help: The UN says 21.6 million people in Yemen, out of a population of 32.6 million, need some sort of humanitarian assistance in 2023, with 17.3 million people expected to face acute food insecurity.

Aid sector: Tiny steps, not big reforms

How the humanitarian sector can learn from its past

It’s easy to become jaded when trying to measure meaningful change in the humanitarian sector. It’s an industry that’s quick to promise sweeping reforms, but far slower to make them happen. Maybe there’s another, more humble, way forward. “The aid system fumbles when it aims big,” Jessica Alexander, The New Humanitarian’s editor-at-large for policy, writes in this reflection examining 25 years of reforms. Instead, she has a modest proposal to stop the humanitarian hamster wheel from spinning: Start small.

There’s clear evidence that big promises – to make aid more locally driven or to empower people in crises, for example – often get stuck in a never-ending series of workshops, panels, and systemic quicksand. Yet it turns out that humanitarians are actually good at the technical stuff. Aid is more effective and professional than it was two decades ago, Alexander writes: Aid workers are better at things like coordinating, assessing needs, and delivering on sanitation and shelter.

Perhaps unmet promises on localisation and accountability could also be reframed in a similar way. Rather than transformative agendas, grand bargains, and participation revolutions, how about unconditional cash grants, more flexible organisational funding, and local leadership on coordination bodies? A handful of organisations and humanitarians are already making these sorts of individual changes. They may sound modest compared to, say, ending power imbalances and overhauling aid. But “taken together”, Alexander writes, “these bite-sized, practical shifts may start to dislodge the underlying problems that have long beset the sector.”

Why it matters in 2023

In 2023, humanitarian leaders will try and jumpstart old (and mostly dormant) pledges to make aid more accountable to people in crises. The humanitarian sector needs to change – it can’t afford not to, given current trajectories. How can it ensure new commitments don’t wind up in the recycling bin? Don’t underestimate the value of a tiny step. When it comes to changing a system that rarely budges, it may be an aid reformer’s best foot forward.

India: Caste discrimination in aid

How India’s caste system keeps Dalits from accessing disaster relief

Ignored as storms loom, shunned from cyclone shelters, excluded from emergency relief, left out of recovery programmes – there’s a glaring but unspoken caste divide throughout the disaster spectrum for India's Dalit community. Viewed by members of other castes as “untouchables”, Dalits particularly struggle during disasters, when community members may often bar them from shared facilities. “Your caste determines what kind of treatment you will get during a disaster,” activist Sangram Mallick tells Dalit journalist Suprakash Majumdar in this eye-opening piece from southern India.

Why it matters in 2023

When the #BlackLivesMatter movement took centre stage in other parts of the globe, a parallel campaign focused on caste discrimination unfolded in South Asia. Dalit communities continue to be marginalised, as Majumdar’s reporting shows. Crises magnify inequalities, and climate-fuelled disasters expose the gaping ones faced by Dalits. “The cyclone or flood may have passed,” writes Majumdar, who identifies as a Dalit journalist. “But for them, and countless more like them, the disaster hasn’t ended.”

A Syrian refugee reflects on EU asylum double standards

Why did we have to freeze in the forest?

“How is it possible that on one border you beat people, and yet on the other you give them soup and cookies? Isn’t this racist?”. In October 2021, Ibrahim, a Syrian refugee from Damascus, crossed the border from Belarus to Poland along with thousands of other asylum seekers and migrants being used as pawns in a political showdown between Belarus and the EU. To avoid being apprehended, beaten, and pushed back to Belarus by Polish security forces, Ibrahim and others had to cross dangerous swamps and hide in the forest for days and sometimes even weeks. At least 27 people have died attempting the crossing in the past two years. Months later, after making it to Germany, Ibrahim watched as the Polish government and security forces welcomed Ukrainians escaping Russia’s invasion with open arms. In this moving first person account, he expresses empathy for Ukrainians being forced from their homes as well as pain and indignation over the vastly different treatment he and other non-European refugees received in Poland and the EU.

Why it matters in 2023

After a very brief hiatus, migration has once again become one of the most salient and polarising issues in European politics. Even as they welcome and support Ukrainians, many countries across the continent are showing an increasingly brazen willingness to flout EU and international law as they seek to keep out refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants from the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and elsewhere. As people escaping wars, crises, and disasters collide with hardline deterrence policies, suffering along the EU’s frontiers will likely increase in the coming year.

Life on the front line of Russia’s invasion

A Ukraine diary: When the war came to me

When Russia invaded Ukraine at the end of February, the peaceful, happy world the anonymous author of this diary knew in their village outside of Kyiv suddenly dissolved. Soon, the front line was less than 200 metres away. Of mixed Ukrainian-Middle Eastern ancestry, the author and their family were no strangers to conflict, but they were still shocked by the level of violence and horror they were witnessing and that was being inflicted on Ukraine. Through words and illustrations, the author kept an intimate record of the terror of the first month of the invasion and its emotional and psychological toll. In November, they wrote a follow-up reflecting on how their village survived and the process of adjusting to the ‘new normal’ of life after the April withdrawal of Russian troops from areas around Kyiv. “No matter how pretty a sunset may be, how intense a distraction, at the back of our minds we are always alert, waiting for the sound of explosions, listening for subtle changes in the wind, always anxious, always vigilant,” they wrote.

Why it matters in 2023

At the end of February, it will have been one year since Russia launched its attempted full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The war has had a devastating humanitarian impact inside Ukraine and has had widespread ripple effects on other crises and aid operations around the world. As it enters its second year, it’s important to remember how it is being experienced by individuals as it continues to impact civilians inside Ukraine materially as well as psychologically and emotionally.

Easing violence in West Africa’s Sahel

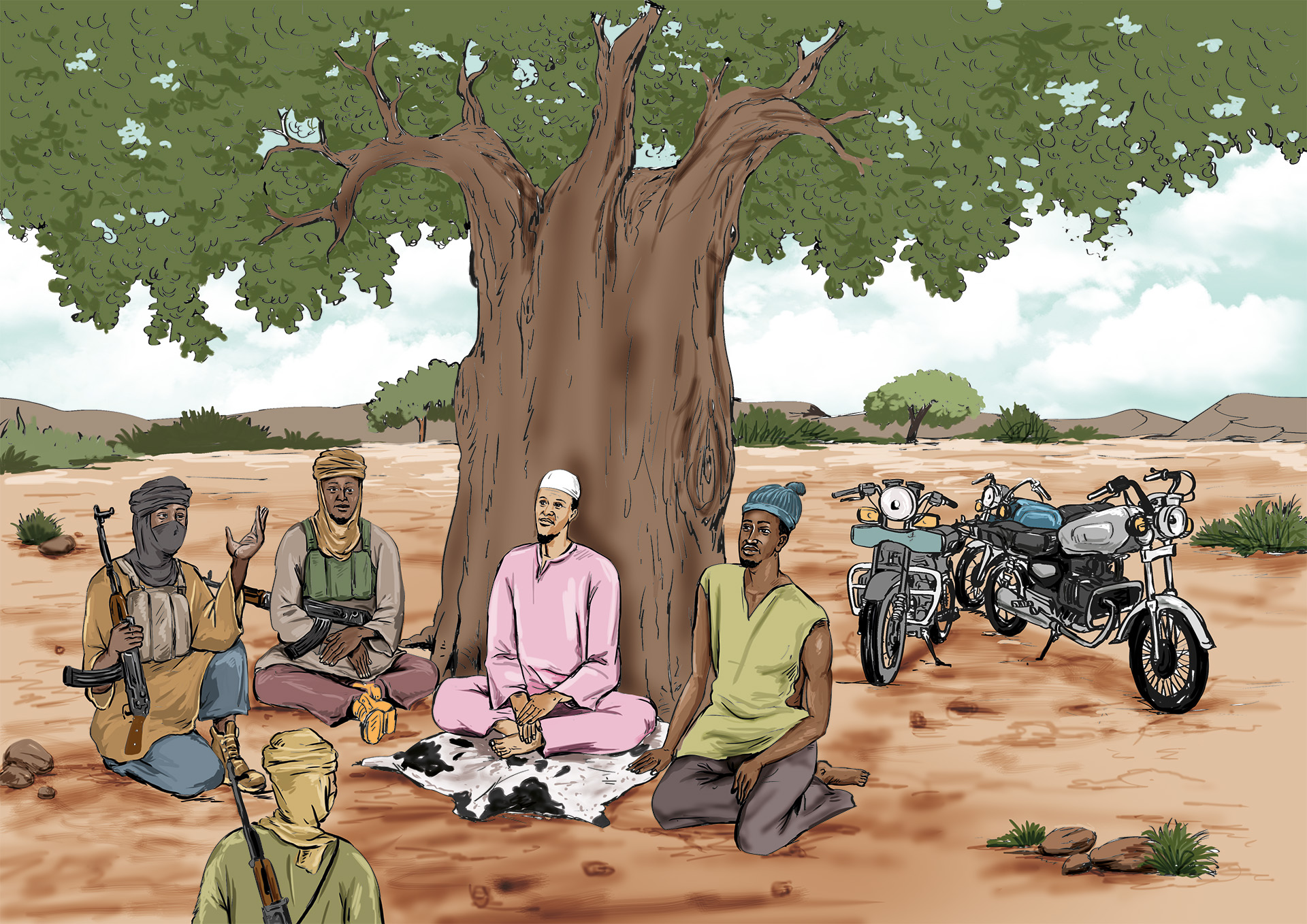

A kidnapped teacher, a fed up farmer, and a push for dialogue with Mali’s militants

As military forces have failed to reverse the violence in West Africa’s jihadist-hit Sahel, some communities have trailblazed a different approach: dialogue with the militants. In recent years, an army of local leaders – schoolteachers and shepherds, bus drivers and businessmen – have struck dozens of hyper-local truces with jihadists in Burkina Faso and Mali. To understand what these efforts entail, take a moment to read our profile of Amadou Guindo – a charismatic farmer who sparked a bottom-up dialogue drive in a volatile part of central Mali. Guindo (not his real name) made contact with an al-Qaeda-linked jihadist cell in 2020 as part of an effort to liberate a local teacher taken hostage by the group. A successful encounter led to further meetings and an agreement that saw Guindo’s commune agree to respect strict sharia law in exchange for jihadists halting attacks. As a semblance of stability returned, community leaders from other communes requested their own meetings with the militants, using the farmer as a guide and fixer. Guindo’s extraordinary story (told by Malian journalist Mamadou Tapily and Africa correspondent Philip Kleinfeld) highlights the everyday courage of local leaders trying to protect their communities in the face of insurgencies. And it illustrates the hard sacrifices, moral quandaries, and personal risks they must navigate along the way.

Why it matters in 2023

Though dialogues have led to ad hoc agreements in certain zones, they have proved fragile and unable to alter the overall downward trajectory of conflict in the Sahel. Civilian deaths and humanitarian needs hit new highs in some areas this year and indicators could well worsen in 2023. Military coups drove instability in Burkina Faso, while Wagner Group mercenaries were involved in heinous abuses in Mali. France, meanwhile, wound down its unpopular Sahel mission after nine years of fighting jihadists.

South Sudan: When peace triggers war

How South Sudan’s peace deal sparked conflict in a town spared by war

It might sound counterintuitive but efforts to bring peace often result in more conflict. When agreements between governments and rebels are seen as rewarding violence, other military actors may use force to get a seat at the table. Settlements between elites can produce states that lack credibility, and electoral processes can create new winners and losers. For a striking case study in a failing war-to-peace transition, check out correspondent Sam Mednick’s dispatch from South Sudan, where fighting has escalated amid a competition for power in the transitional unity government. Mednick travelled to the western county of Tambura, which escaped the civil war unscathed but has seen tens of thousands of people displaced during “peacetime”. The power-sharing provisions of the national peace agreement (signed in 2018) disrupted Tambura’s political status quo, and local elites then polarised communities. “When the civil war ended, we felt happy we survived it, but unfortunately war erupted,” one resident told Mednick. “During the war, I wasn’t worried about being in Tambura,” said another. “But now there is no sign of lasting peace… Even if someone comes to discuss peace, we won’t believe them.”

Why it matters in 2023

President Salva Kiir and his long-time rival, Vice President Riek Machar, have been trying to project an image of national unity and reconciliation in recent years. But that’s becoming harder to sustain as large-scale conflict continues in the countryside and humanitarian indicators reach levels unseen even during the civil war. The power-sharing accord needs a major rethink, but the international community still sees it as the only game in town. More conflict seems inevitable in 2023, even as communities struggle to cope with interlocking crises that have left nearly eight million people severely hungry.

Lebanon’s collapse, behind and beyond the headlines

WhatsApp, Lebanon?

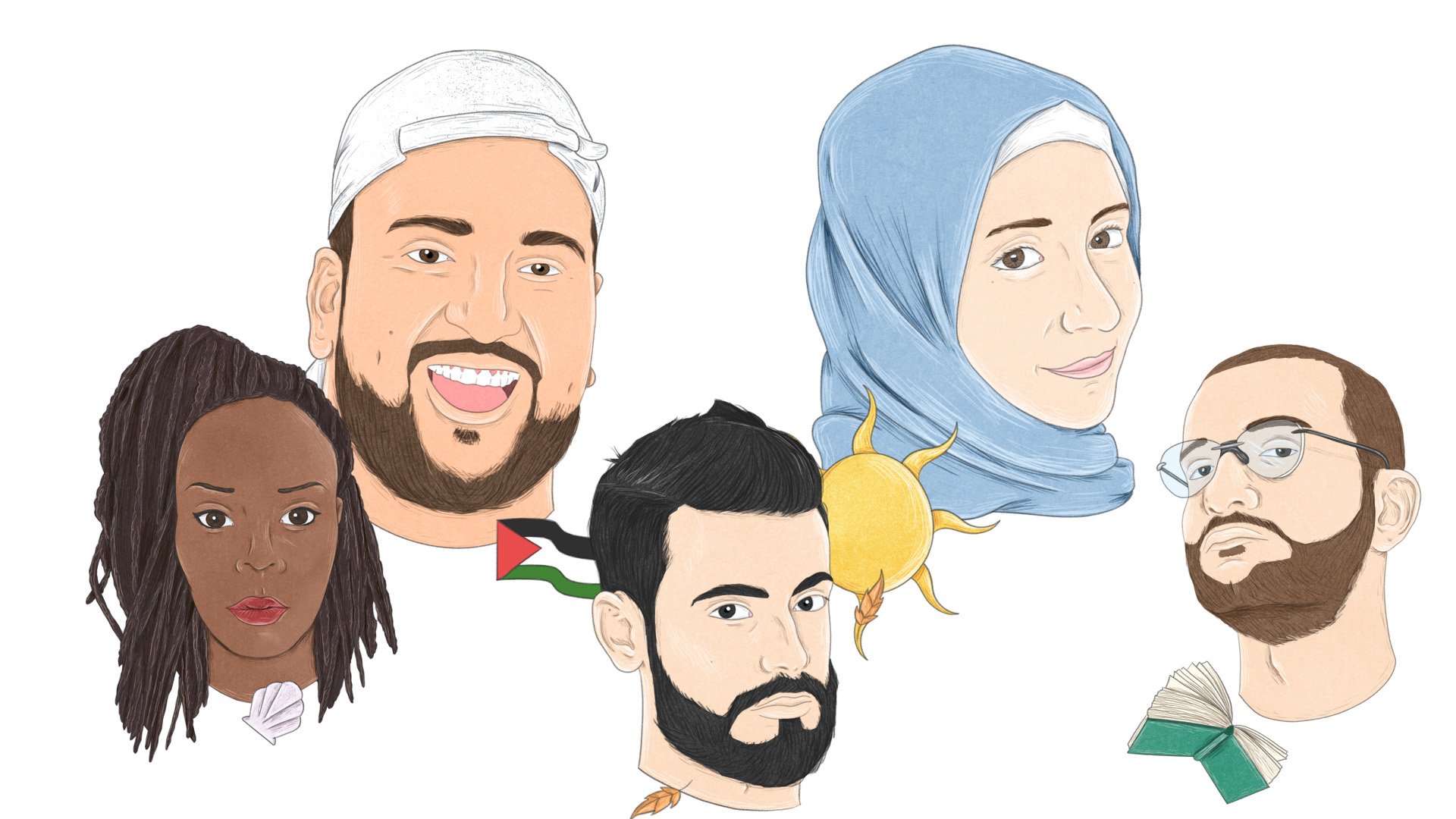

Over the past four years, Lebanon has been falling deeper and deeper into what the World Bank says is likely to be one of the world’s worst economic crises since the 1850s. This means hyperinflation, soaring poverty rates, shortages of crucial medications, almost no electricity, and rising prices of just about everything. The collapse has been devastating, impacting almost every part of life, but hasn’t often made the headlines. This illustrated timeline, available in Arabic and English, brings you into the heart of it all through the phone screens of five young people who live in Lebanon: Afaf, Bassel, Mohamad, Roger, and Roza. Wait with them in unending bank queues, stay up late as they try to keep warm through unheated nights, and live through the moments of Lebanon’s crisis that did break through to the news, like the massive explosion that tore through Beirut in August 2020.

Why it matters in 2023

Life for the 6.7 million people who live in Lebanon, including the five WhatsAppers, is only getting worse. People are having to cut back on food, and some are so desperate that they are robbing banks just to get their own money, frozen in accounts they can’t access. A cholera outbreak that began in September in Syria quickly spread across the border; the fact that the disease has been able to thrive is yet another sign of the country’s deterioration, with clean water increasingly unaffordable and the health system overstretched. Lebanon’s political paralysis means the country is heading into the new year with only a caretaker government and no president at all, while $3 billion in loans from the IMF hasn’t arrived because financial institutions haven’t made the required reforms.