The last time I wrote something like this, I was finishing up my near-daily war diary. It was the end of March. Russian forces were still dangerously close to where I live in a village near Kyiv. My family was still fearing the worst: a Russian occupation that could last for years.

Since then, our village – which was never taken but saw us trapped terrifyingly close to the front line for more than a month – has been liberated. The fighting that was only 100 metres away is now more than 100 kilometres away.

At a glance, you could be forgiven for thinking that life has returned to some kind of normal: shops are open; buses are running; Kyiv’s streets are bustling and noisy again.

But things are not normal. Somewhere over the horizon, something explodes from time to time. Every other day, we get alerts for incoming air raids. Since early October, Russia has intensified its bombardment of civilian infrastructure in Ukraine – especially targeting power stations – in an attempt to knock out critical services ahead of winter.

These strikes snap me back to the early days of the war. But it’s different now: The sense of sheer terror I felt at the beginning of the invasion has gone. It has been replaced by anger and a desire to persevere.

Still, one thing is clear: This war has changed us all. We are not the same people we were before it began. No matter how pretty a sunset may be, how intense a distraction, at the back of our minds we are always alert, waiting for the sound of explosions, listening for subtle changes in the wind, always anxious, always vigilant.

Final days

At the start of the invasion – as an act of resistance against the Russians, and because we didn’t want to abandon our home – my family and I made a conscious decision not to flee. But it was only after our village was liberated that we fully realised how dangerous our situation had been, and how lucky we were to survive.

Towards the end of the occupation, the explosions in our vicinity were becoming like the weather: We knew they were there, but we didn’t pay much attention to them unless we were caught outside. At first, I would go upstairs to take photographs of the smoke rising after a strike. I soon stopped – there was just so much of it every day.

We didn’t know what exactly was happening around us. Information came in endless waves, too fast to check and verify. I couldn’t tell if the shells zipping overhead and landing nearby had been fired by Ukrainian or Russian troops, or who they were targeting.

The waking nightmare we had lived for more than a month was over. The Russians had lost the battle for Kyiv.

The days preceding the collapse of Russian forces in our area were some of the scariest. Every day, the fires and smoke behind the forest near our house became more frequent and more intense. We could hear the artillery shells whistle as they flew overhead, physically cutting the air above us. We could tell the Russians were being hit hard. By this point, we had a better idea where their positions were – smoke never stopped rising from where we suspected they had dug themselves in.

The last night of the occupation, a huge fire burned in the town next to us, just three kilometres away. The flames were so high I was afraid they would reach us. The next morning, we saw the first videos of liberation. Ecstatic locals were crying and greeting Muslim Tatar fighters who were part of the Ukrainian army’s volunteer Crimea battalion.

Watching the videos, my father and I started crying tears of joy. We realised the worst for us had passed: The waking nightmare we had lived for more than a month was over. The Russians had lost the battle for Kyiv.

What saved us?

Our tiny village probably should have been occupied during the first days of Russia’s attempted blitzkrieg.

After the Russians were pushed back, along with an international journalist friend of mine, we interviewed the local government official in charge of my village and spoke to others who had survived the assault.

That is what saved us: mud, outdated maps, and the efforts of those brave enough to fight back.

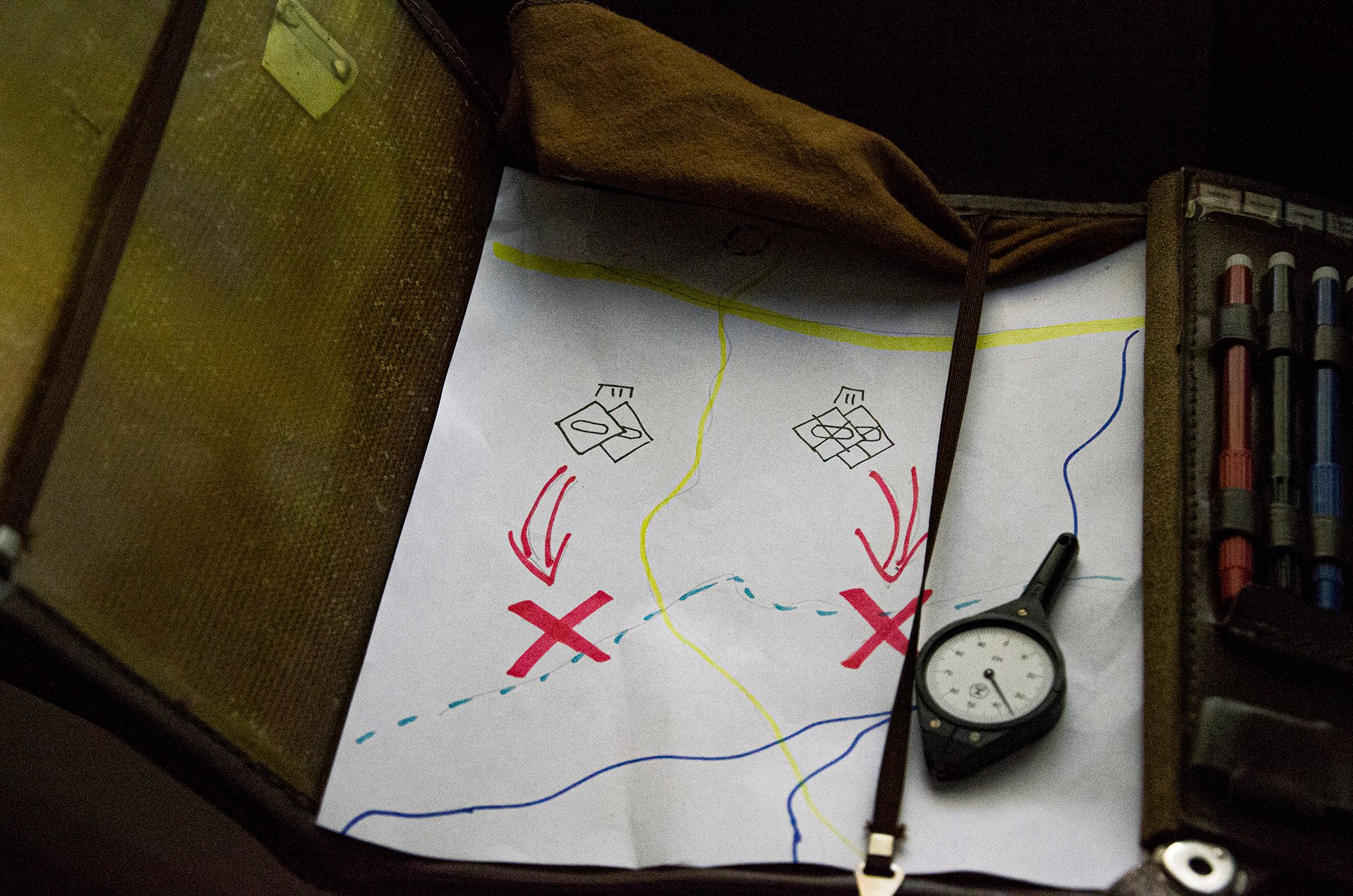

Some said my village – which only had around 100 officially registered residents before the war – wasn’t actually marked on the outdated maps the Russians were using. Once they realised it was there, they tried to break through from an adjacent village to capture it, but they faced fierce resistance from the Ukrainian army, local defence militias, and residents.

Their tanks and war vehicles also got bogged down in the mud of early spring. In Eastern Europe this mud has a name: rasputitsa – referring to the season when unpaved roads become difficult to pass because of rain and melting snow. Rasputitsa has thwarted invaders since at least the Napoleonic wars of the early 1800s.

That is what saved us: mud, outdated maps, and the efforts of those brave enough to fight back.

The toll of occupation

Other villages nearby didn’t get off so lightly. The first days after liberation revealed the horrors of torture and execution carried out by Russian forces. The scale of the killing in Bucha – where 458 bodies were dumped in a mass grave – grabbed international headlines. But similar atrocities were replicated in many of the occupied villages.

Relatives of ours in towns that came under Russian control were forced to live in cellars or basements. The Russians used them as human shields, refusing to let them flee to safety.

I remember speaking to some of our relatives in the village of Motyzhn on the phone. As the Russian army closed in and explosions echoed down the line, they cried and bid us farewell. When we spoke to them the next day, their voices had changed. We understood that the village was occupied and Russian soldiers were listening in to our conversation.

I knew those people. They had been in the orbit of my life. And there they were under a headline about war crimes and human brutality.

Those relatives decided to make a break for it. They loaded into two cars and burst out of Motyzhn. Even though the cars were full of women and children, the Russian soldiers holding them hostage opened fire and shelled the road in an attempt to kill them. People in the village started referring to it as “the road to hell”. But those relatives were fortunate. They survived.

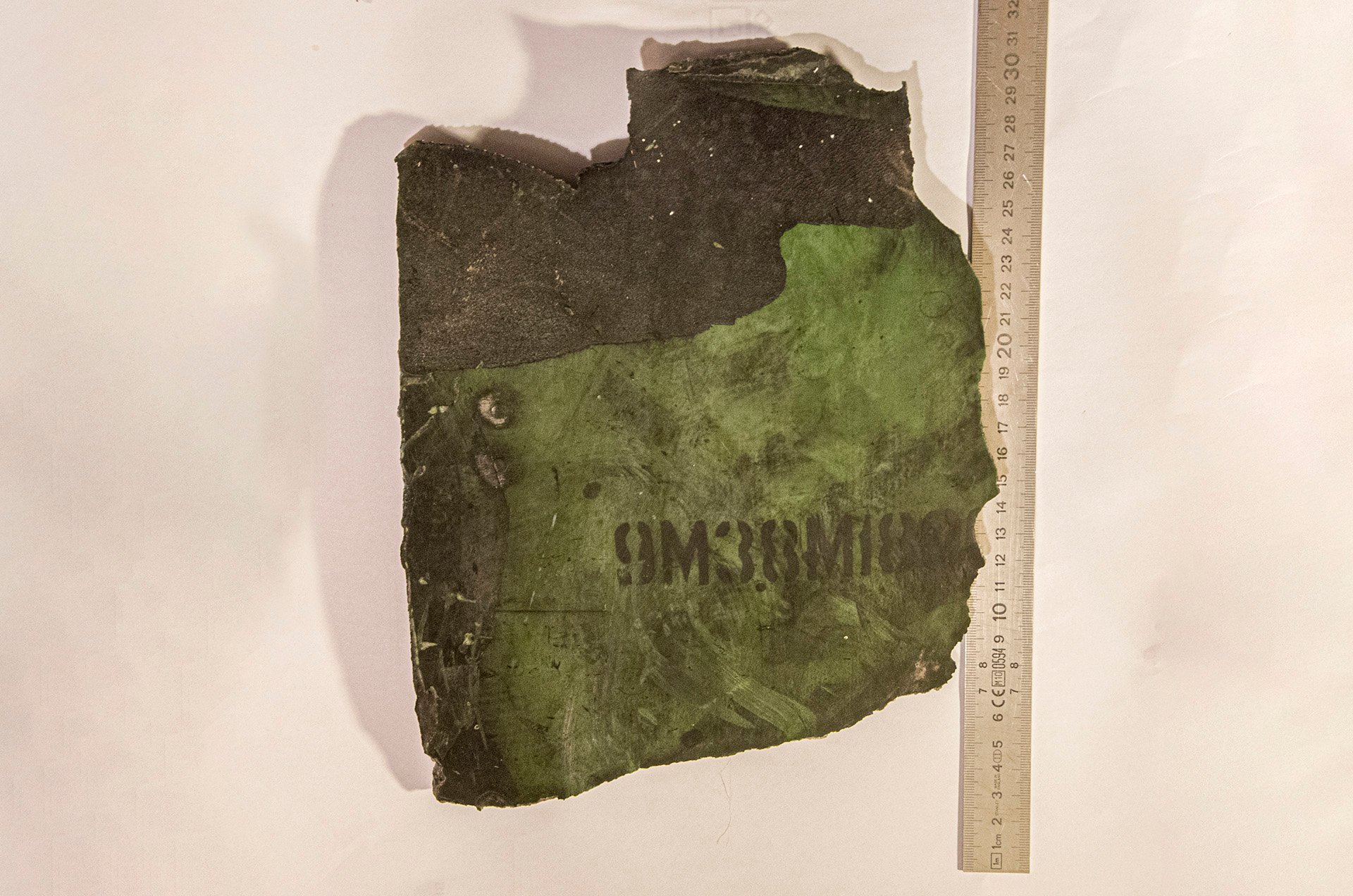

Our other relatives in Motyzhn were not lucky. One was the head of the local village council. The Russians tortured her and her entire family. They were executed with gunshots to the head. After the Russians fled, their bodies were found in a shallow grave, with their hands bound.

Pictures of the grave were carried in the international news. I knew those people. They had been in the orbit of my life. And there they were under a headline about war crimes and human brutality. Thinking about it gives me a knot in my stomach that feels like a black hole.

The gamble we took

I could go on and on recounting horrors like this: of women, children, and the elderly being raped; of people being executed in front of their families. And these are only the stories I have heard first hand from people I know. Everywhere that the Russian army has been forced back from, similar stories emerge – most recently in cities in the east like Izium.

If the Russians had broken through to my village, it’s likely that my father, my brother, and I would all have been executed.

I cannot imagine the true extent of the toll of this war. Perhaps it will be unmasked if and when this is all over. But after the smoke settled in our region, I began to understand the gamble my family took in deciding to stay: If the Russians had broken through to my village, it’s likely that my father, my brother, and I would all have been executed.

Many men between the ages of 16 and 60 in our region were killed because Russian soldiers viewed them as potential threats. The sheer number of deaths means these murders weren’t one-off examples of excess by individual soldiers but part of a premeditated and sanctioned strategy.

I still don’t fully know how to deal with this. Thinking back on that period brings back an intense feeling of dread, as if walls with giant Zs – Russia’s war symbol – are closing in on me again.

However, that time is over, and now at least those of us who live close to Kyiv are free.

It’s not over

The war is still consuming parts of Ukraine. As I write this, the Ukrainian army is liberating territory in the northeast and south of the country. Until a few weeks ago, it felt like that territory was lost forever. Now, I’m once again experiencing the exhilaration of liberation and freedom – this time vicariously.

The more desperate Russia becomes, the more it flails, lobbing bombs and rockets at Ukrainian infrastructure and civilians.

Everywhere the occupation is rolled back, the same emotional rollercoaster plays out – between ecstatic joy at liberation on the one hand and revulsion at the horrors and devastation the Russians leave behind on the other.

We will probably never recover from the emotional toll of this war. I sometimes feel I am becoming too cold and insensitive. Scenes of death and destruction touch me less and less. Yet, at other times, I collapse, crying for almost no real reason at all.

The sacrifices we are making will not be for nothing.

My family, and other people in my village, are safer and better off than we were six months ago. We no longer meticulously lock every door to the house. But the tape we put on the windows to keep them from shattering is still there. There’s still a curfew and blackout hours, and at night we can’t leave home. The war has found a way to seep into my dreams and subconscious. I do my best to shrug it off – to enjoy the beautiful day outside and the laughter of my loved ones.

Sometimes, I realise how quiet it has become with no aircraft flying overhead – until, again, they do. I sit in the night, writing these words with the lights turned off. Outside, the sound of the air is saturated. Jet engines, drones, explosions – a cacophony of excessive aggression. But in the end, life goes on. It’s just a matter of adjusting my routine.

I still find myself dreaming about the post-war period: reconstruction, helping rebuild the country the way we deserve it to be; free, with a functional democratic state that enables people to live with equality and dignity. The sacrifices we are making will not be for nothing. Every drop of tomorrow is going to be precious, and we will feel that as an entire nation. But, we are not there yet. The war still goes on, and as long as it does, the future is still uncertain and unknown.

Edited by Eric Reidy.