When Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza announced he was standing for a third term in office in April 2015, the move sparked mass protests, an attempted coup, and a bloody crackdown that saw more than 1,000 people killed and hundreds of thousands flee to neighbouring countries.

Five years on, the former rebel leader is set to stand aside as millions of Burundians head back to the polls on 20 May, but residents, civil society groups, and human rights observers say the violence that characterised his third term remains rife – and could escalate further if election results are contested.

-

At a glance: Elections in Burundi

- Pierre Nkurunziza standing aside after 15 years in power.

- Main opposition party targeted in deadly crackdown.

- Further violence expected if results are contested.

- Repression driven underground in months preceding the polls.

- Coronavirus response takes backseat as WHO officials expelled.

Clashes between members of the ruling and opposition parties have been reported across the country in recent days, while a significant but unknown number of people are believed to have been killed in the months preceding – often in remote rural areas and in far murkier circumstances than 2015, when bodies were found dumped on roadsides in Burundi's biggest cities.

The ruling party’s control over the electoral commission, and the absence of international election observers, means the retired army general replacing Nkurunziza, Evariste Ndayishimiye, is expected to beat the other six candidates running.

But the veteran leader of the main opposition National Freedom Council (CNL) party, Agathon Rwasa, has indicated he will dispute the result if it goes against him, potentially triggering a new political crisis in the small East African nation.

“Each party is saying they will win,” said Mathieu Sake, the chairman of ACPDH, a Burundian human rights organisation. “If we do not pay attention, there will be more violence.”

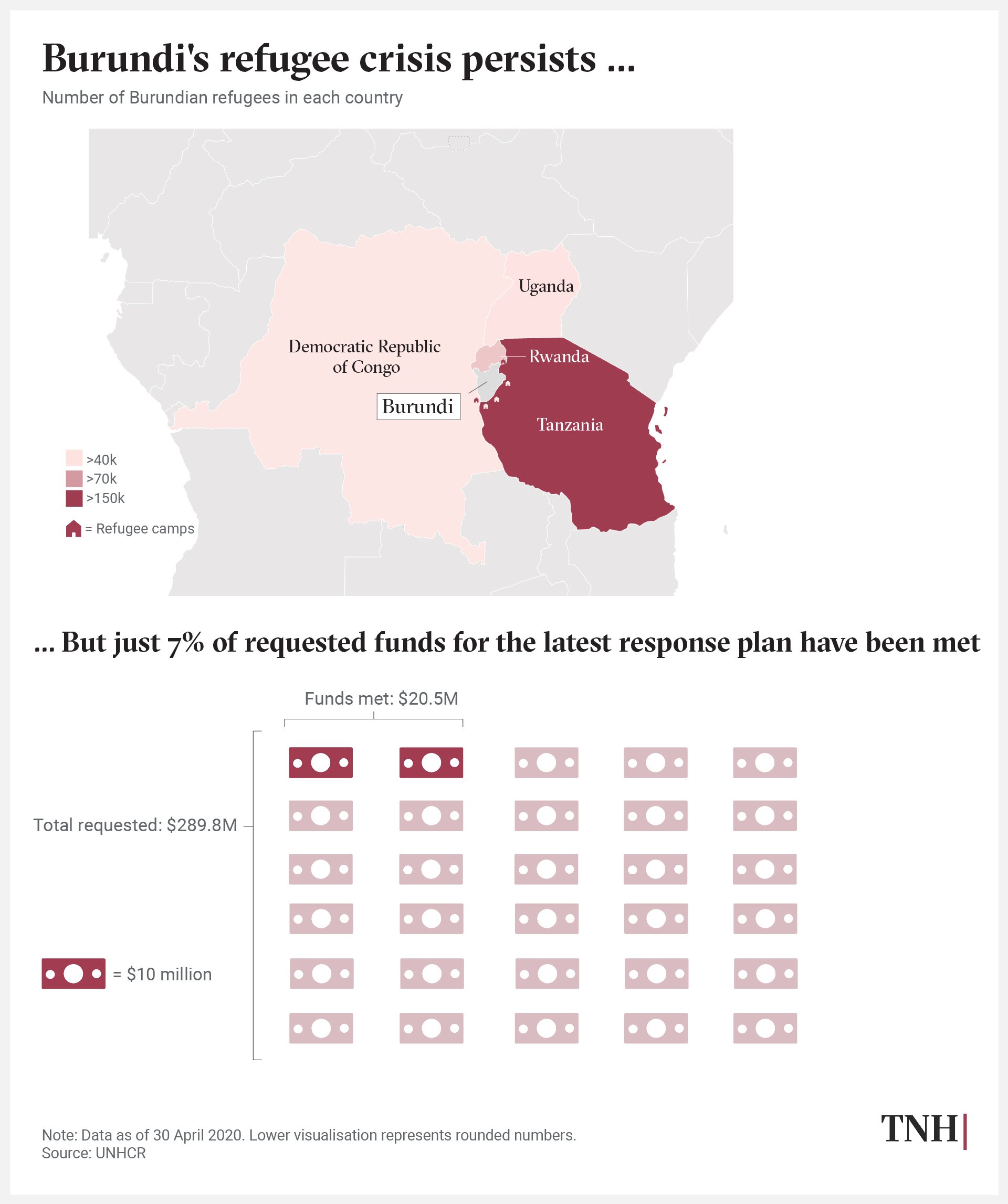

As the outcome is awaited, more than 330,000 refugees are weighing up their options in underfunded camps in neighbouring countries, while millions more Burundians continue to suffer under years of repression and a broken economy.

“Each party is saying they will win. If we do not pay attention, there will be more violence.”

The new president will also have to deal with the coronavirus, which Burundian doctors and nurses say has been spreading even as political parties have held mass rallies, and as the authorities have expelled the World Health Organisation’s top officials in the country without explanation.

Clashes in the countryside

Nkurunziza came to power in Burundi in 2005 following a 12-year civil war in which he fought as a leader of the CNDD-FDD, a Hutu rebel group that became the ruling political party – though one that never quite shed its wartime ways.

After a decade as president, he won a third mandate in 2015 amid an opposition boycott and mass protests by thousands of Burundians who said the move violated a constitutional two-term limit.

Read more → Coronavirus response takes backseat as election looms in Burundi

As the crisis escalated, and criticism mounted, the ruling party doubled down: it withdrew from the International Criminal Court – the first country to do so – closed down the UN’s local rights office, and rejected inquiry after inquiry into abuses.

After targeting protesters, civil society groups, lawyers, and journalists, the ruling party’s attention has narrowed in the current pre-election period to the CNL, whose members have been attacked in coordinated ambushes and beaten to death, according to rights groups.

The dirty work has mostly been carried out by the ruling party’s youth wing – the Imbonerakure or “those who see far” in the local Kirundi language – though police officials have been casting the CNL as instigators and arresting their members.

“They are imprisoned without being able to seek medical help,” said Emmanuel Nibizi, the vice president of Ligue Iteka, one of Burundi’s leading rights groups.

The violence has increased markedly in recent days, with countryside towns like Muyinga in northeastern Burundi bearing the brunt. Residents who spoke to TNH described ambushes against CNL supporters, bricks thrown at cars, and members beaten with sticks.

One man, whose name TNH decided to withhold due to the security risks, said his CNL-voting son was “sentenced to many years” in prison after a scrap with the Imbonerakure two weeks ago, while another said he witnessed “terrible fights” in recent days, all of which ended in CNL members behind bars.

“When it is [time] to punish those involved in clashes, it is only CNL who are arrested,” the first said.

A member of the Imbonerakure in Muyinga told TNH that CNL supporters should also bear some responsibility – not for participating in violence but for joining a party that cannot physically protect them.

“When you lean on a weak tree and it falls, you must fall with it,” said the youth party member.

Hidden violence

While violence like this has spilled into open view, the Burundi Human Rights Initiative (BHRI) – an independent rights group monitoring the country – says the ruling party normally seeks to hide evidence of repression.

Killings are no longer common in big cities, but in rural areas residents regularly find unidentified bodies – often showing signs of torture – dumped in rivers and streams or hanging from trees far from presumed crime scenes.

Local authorities bury the bodies before questions can be asked, and some of those involved have been told not to take photos that might end up on social media. In the rare event a witness is found, they’re often too afraid to speak out.

Secret cemeteries hidden in countryside forests and banana groves have also been documented in different parts of Burundi by the BHRI, which said the strategy is designed to hide violence and project an image of calm ahead of elections.

“It’s hard to really clarify who has been buried there and what has happened,” said Thijs Van Laer, a BHRI researcher.

Ordinary residents are suffering in myriad ways too, mostly at the hands of the Imbonerakure, whose tens of thousands of members help project ruling party power – and enforce its authority – across Burundi.

Read more → Burundi’s humanitarian crisis: An inconvenient truth for the ruling party

The group has little legal authority but rights organisations say its members have forced villagers to pay arbitrary taxes for harvesting crops, grazing animals, accessing drinking wells, and even for collecting lake water.

Lacking resources to fund the elections, the government tasked the Imbonerakure in 2017 with collecting contributions from the public. But it kept some of the money for itself, and forced already impoverished residents to pay multiple times over.

“I can’t tell you how much I have paid for these elections,” said Omar Moussa, a 60-year-old shopkeeper from Muyinga who contributed as an individual, a market trader, a member of the ruling party, and as a parent of voting age children.

Refugee rights groups say the Imbonerakure regularly harass returned refugees, who they consider traitors or accuse of associating with opposition groups. Expecting fresh violence, recent arrivals often choose to live in provinces close to the border rather than their home villages.

What happens next?

Few Burundians expect the polls to be free and fair given the electoral commission’s ruling party bias. The only group of election observers allowed into the country is now being forced to sit out the vote in a 14-day quarantine.

Some diplomats and analysts see Ndayishimiye as a reformist candidate who could help hoist Burundi out of years of international isolation that has seen donors pull bilateral assistance.

Ndayishimiye has a better human rights record than his peers but critics say he has done little to halt his party’s authoritarian drift, and will be unable to break free from Nkurunziza and the powerful military generals thought to have stopped him standing for a fourth term.

“It is not just Nkurunziza who is responsible for all of this,” said Nibizi of Ligue Iteka. “He has got collaborators.”

Having failed in past elections, Rwasa said the public will not accept a “stolen” vote, and is expected to contest the results if he loses.

“He and his family seem convinced of their victory,” said Willy Nindorera, a Burundian researcher. “We can... expect protests, especially since critics are already coming from everywhere to denounce major [electoral] irregularities.”

Rwasa may be hoping the CNL’s large, mostly rural support base will come out onto the streets following the poll, but the climate of fear in Burundi may undermine efforts to revive a protest movement as broad and as popular as in 2015.

“Refugees do not trust the electoral process. They think that after the elections a political crisis can be unleashed.”

Whoever prevails will inherit an economy in the doldrums and a growing humanitarian caseload that includes outbreaks of malaria and measles and tens of thousands of recent flood victims. Hospital workers in Bujumbura told TNH that the coronavirus is also spreading, despite the country recording just 42 confirmed cases and authorities claiming Burundi would be protected by divine intervention.

Mending bridges with opposition groups won’t be easy after the failure of various meditation efforts. And convincing hundreds of thousands of refugees to return home will be an even taller order.

In the camps in neighbouring Tanzania, refugees have faced periodic deportation threats by authorities from both countries, restrictions on their livelihoods, and cuts to basic food rations. Still, the vast majority choose to remain.

“Refugees do not trust the electoral process,” said one camp resident in Tanzania who asked not to be named. “They think that after the elections a political crisis can be unleashed.”

pk/ag