Since fleeing his home in Nigeria’s Borno State six years ago, retired civil servant Iddrisu Ibrahim Halilu has fought tirelessly on behalf of those who, like him, have been displaced by violence meted out by Boko Haram.

Halilu, 62, is the health coordinator of a camp in the Durumi district of Abuja where some 3,000 people have made a temporary home. In all, the Boko Haram insurgency has claimed more than 20,000 lives and uprooted some 2.4 million people.

Reed-thin with greying hair and a leathery face, Halilu is seen as a saviour by fellow residents. He spends much of his time trying to source funds to meet the urgent medical needs of people like motorbike-taxi driver Jafaru Ahmed, who suffered multiple fractures in a hit-and-run accident in April.

Unable to pay for medical care, Ahmed was left largely unattended as he lay in a coma with badly swollen limbs in Abuja’s National Hospital. That was until Halilu facilitated his transfer to a cheaper facility, where he now receives much-needed treatment.

Halilu’s work is never done: Ahmed may be in better shape, but other camp residents have varying degrees of medical needs. As health coordinator, he feels it is his duty to continue sourcing funds.

People call him “Baba IDP” – father of internally displaced persons – a term of endearment that suits him.

A widower who has outlived his own children, Halilu looks on his fellow displaced as his family now, and is deeply troubled by the frequent failure of his relentless fundraising efforts.

The concentration of local and international health NGOs in Nigeria’s Boko Haram-ravaged northeast means problems in places like Abuja, even though it is the Nigerian capital, are often overlooked.

What is local aid?

- The global aid sector has broadly committed to an agenda to “localise” aid – putting more power in the hands of locals working on the ground where emergencies hit.

Who are local aid workers?

- Local humanitarian aid may include local NGOs, civil society groups and community leaders, local governments, indigenous peoples, as well as people who are themselves affected by crises, including refugees and displaced people working to help their own communities.

Why local aid?

- The aim of of the “localisation” agenda is to improve humanitarian response, by making it faster, more efficient, and more in tune with the needs of the tens of millions of people who receive humanitarian aid each year. Local aid workers are closer to the ground, can access areas that international aid groups can’t reach, and know the needs of their own communities.

- The global humanitarian system is overstretched. In 2017, the UN asked for a record $22.2 billion to cover emergencies in 33 countries.

- This includes the crisis in northeast Nigeria, where conflict between the government and Boko Haram is in its ninth year. The UN says it needs more than $1 billion to bring aid to more than 6.1 million people in Nigeria. So far, less than half of this has been funded, but humanitarian needs continue to rise.

Local NGOs, with little capacity to administer treatment, visit the camp occasionally, but international NGOs are largely absent. Contacted by IRIN, Phillips Aruna, country director for Médecins Sans Frontières, said the medical charity was not aware of the needs of IDPs in Abuja, and promised to investigate.

A man on a mission

Given the absence of a structured system, the burden of healthcare and advocacy for thousands of displaced people inevitably falls on the few educated members of the camp.

Halilu studied at the University of Mogadishu in the 1970s, and it was in Somalia that he first came in contact with insurgents and violent extremists.

When Boko Haram started spreading messages of hate in Maiduguri, his hometown, Halilu was outspoken against them and had to flee Borno State in 2009 after the group targeted him.

Every day at 8am, Halilu reports at the secretariat of the National Commission for Refugees, Migrants and IDPs in the capital, hoping against hope for an audience with the commissioner.

He dons his usual garb: a blue-chequered waistcoat complete with the logo of “St Regis Secondary School” on top of a white-and-brown striped polo shirt.

Pairing these with a red baseball cap or, occasionally, an embroidered fila (traditional hat), and sporting an unkempt, grey beard – Halilu always stands out from the crowd. Employees of the secretariat often point and whisper loudly, “Who is that man?” and “Why is he always here?” But the whispers matter little to him.

Halilu has written dozens of letters to the commission, marked “SOS” and seeking financial assistance. When they go unanswered, an already-poor Halilu often resorts to taking out personal loans to make sure feed patients get fed.

Across Abuja, more than 10,000 displaced persons face similarly poor health conditions. But they have to compete for attention and assistance with millions in the northeast: last year, thousands of IDPs in Borno State took to the streets to protest appalling living conditions, demanding for the freedom to return to Bama, their hometown.

Debtors detained

Doctors at Abuja’s National Hospital have grown weary of treating the IDPs Halilu brings in, especially as so few are able to pay. It is hospital practice to keep in patients who haven’t settled their bills, even after they’ve been healed.

When IRIN caught up with him, Halilu was working to secure the release of one such patient.

"I don’t know where to start the journey because I need money for the hospital bills,” Halilu said, frustration etched into his weathered face. He did not understand how the government could neglect IDPs who live just a few miles from Aso Rock, the presidential villa.

“We can’t afford even 100 naira (28 US cents) [and] we are talking of bills of 100,000 naira, 200,000 naira,” he said.

The National Commission for Refugees, Migrants and IDPs has not been forthcoming with financial aid despite a supposed 2017 agreement between the commission, the IDPs, and the National Hospital in Abuja.

National Hospital spokesman Tayo Haastrup said the commissioner, Hajiya Sadiya Umar Farouk, had failed to make good on a verbal commitment she gave last year to pay IDP medical bills.

“We wrote to the commission, stating that the IDPs had a bill of over five million naira to pay, but they wrote back [saying] that they are not aware of what we are saying,’’ Haastrup said. “They (the refugee commission) should support us, they should even pay money in advance for their care.”

The commission failed to respond to IRIN’s request for comment.

Cramped conditions

Halilu explained how diseases spread easily as the camp’s batchas – makeshift shelters fashioned from flimsy tarpaulin sheets and old cement sacks – are so close together.

Last year, a mysterious sickness characterised by persistent coughing ran quickly through the camp, particularly affecting children.

Halilu’s batcha is built near a refuse dump, where residents defecate in the open for lack of sufficient latrines. Inside it, beneath the many books he has left open and a single mattress, are paperboards – a flimsy attempt to keep rainwater at bay.

The onset of rains, which run from June to September and are forecast to be especially heavy this year, has made things even worse in Abuja’s camps and led to an outbreak of cholera.

“Be Human. Defend the Undefended. Help the Helpless.”

Umaru Gola, a smallish man in his forties with a tribal mark that runs diagonally from the bridge of his nose to his left cheek, is just recovering from a bout of the disease.

When Boko Haram attacked Gwoza, a district of Borno, in August 2014, Gola’s four siblings and parents were among those killed. He himself only escaped the massacre by chance.

Gola used to own three stores in Gwoza. “I was running a business of almost 15 million naira. Now, I don’t have [even] 100,000 naira,” he said.

To keep himself busy, Gola now focuses on his job as the camp’s spokesperson.

“Look at all our batcha now: if you throw a cup of water on [the roof] and go inside you will see the water in the room,” Gola said. The materials used to make the huts have gone up in price, putting running repairs out of the reach of many camp residents.

Gola had hoped that in a camp in the capital, right under the nose of the president, he and his young family would be able to safely get on with life after Boko Haram.

But what little sense of security they’ve managed to hold on to is now threatened by the unsanitary health conditions.

“If you look around,” Gola said, gesturing towards the camp, “most of our problems [are related to] the health [situation].”

Hepatitis

A few months ago, Halilu took a few camp residents to the hospital to donate blood. To his shock, all of them tested positive for hepatitis B, a potentially deadly liver infection that can be passed on through contact with blood and other bodily fluids.

When a local NGO tested the rest of the camp’s population, they found around 60 percent of them were infected.

According to Halilu, the government hasn’t made available any vaccines, which are 95 percent effective in preventing infection. Yet, he is certain the commissioner is aware of the outbreak, as he informed her in one of his many letters.

The shelves of the small camp clinic are empty and the doctor who volunteers to treat residents visits only occasionally. Poor case-surveillance and documentation mean those infected with the virus continue to mix freely with the larger population, putting thousands at risk, according to Halilu.

A health ministry official who chose to be identified only as Comfort told IRIN the ministry wasn’t aware of the outbreak and said residents should complain directly to the ministry.

When Halilu first arrived in Abuja six years ago he had hoped to meet the interior minister to raise the plight of those affected by Boko Haram. The minister was unavailable, so he wrote him a letter. Since then, he hasn’t stopped writing, to anyone he thinks can help.

He sends copies to the Nigerian Human Rights Commission, the health minister, the UN’s refugee agency, even the president. When he visits the commission in person, he is told to put his complaint in writing, so he writes another letter.

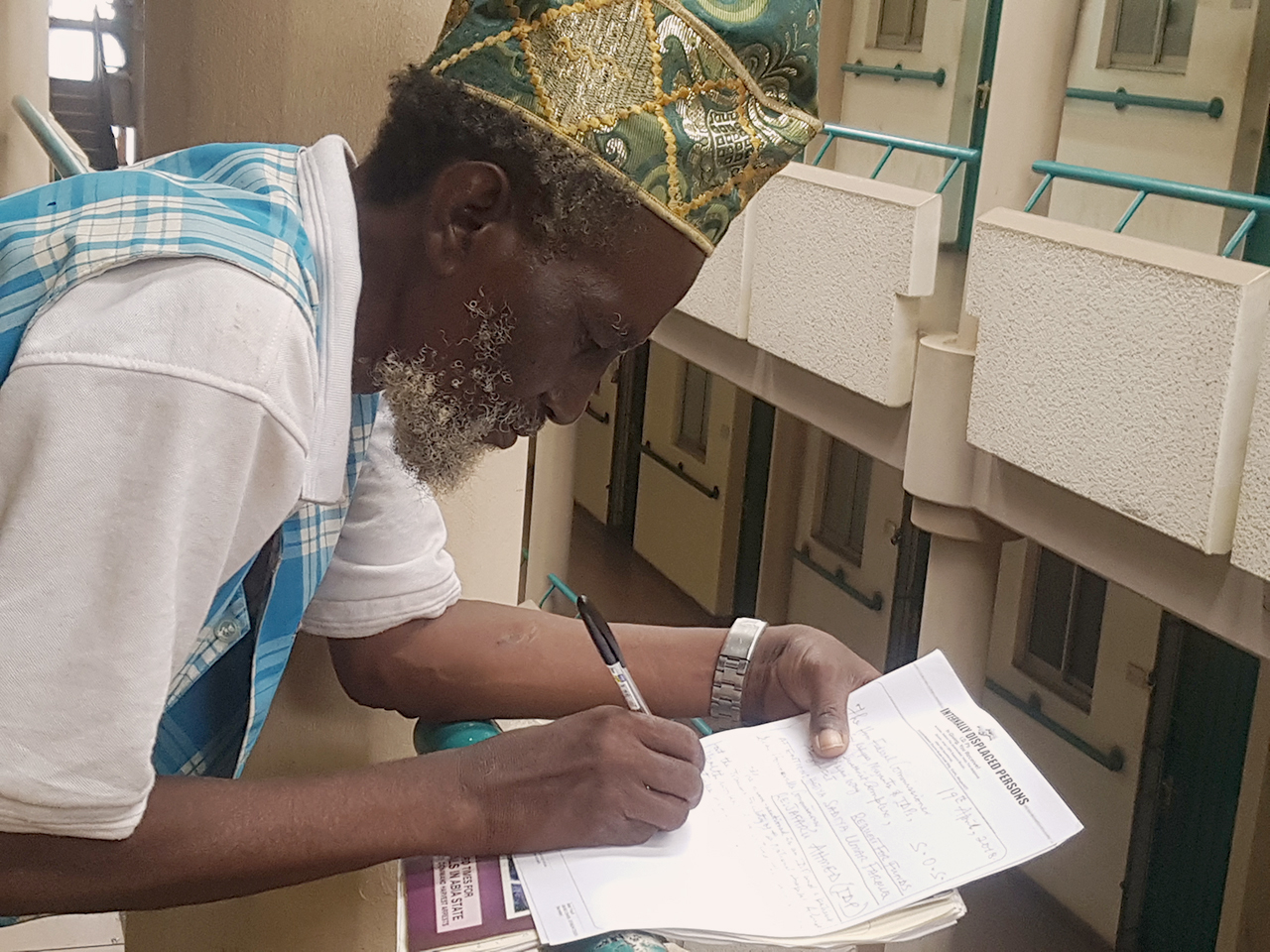

Everywhere he goes, Baba IDP is armed and ready to fire off further missives, carrying sheafs of paper topped with a typed letterhead of his own devising: “INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS” in bold capitals. Underneath is a simple entreaty: “Be Human. Defend the Undefended. Help the Helpless.”

sl/am/ag