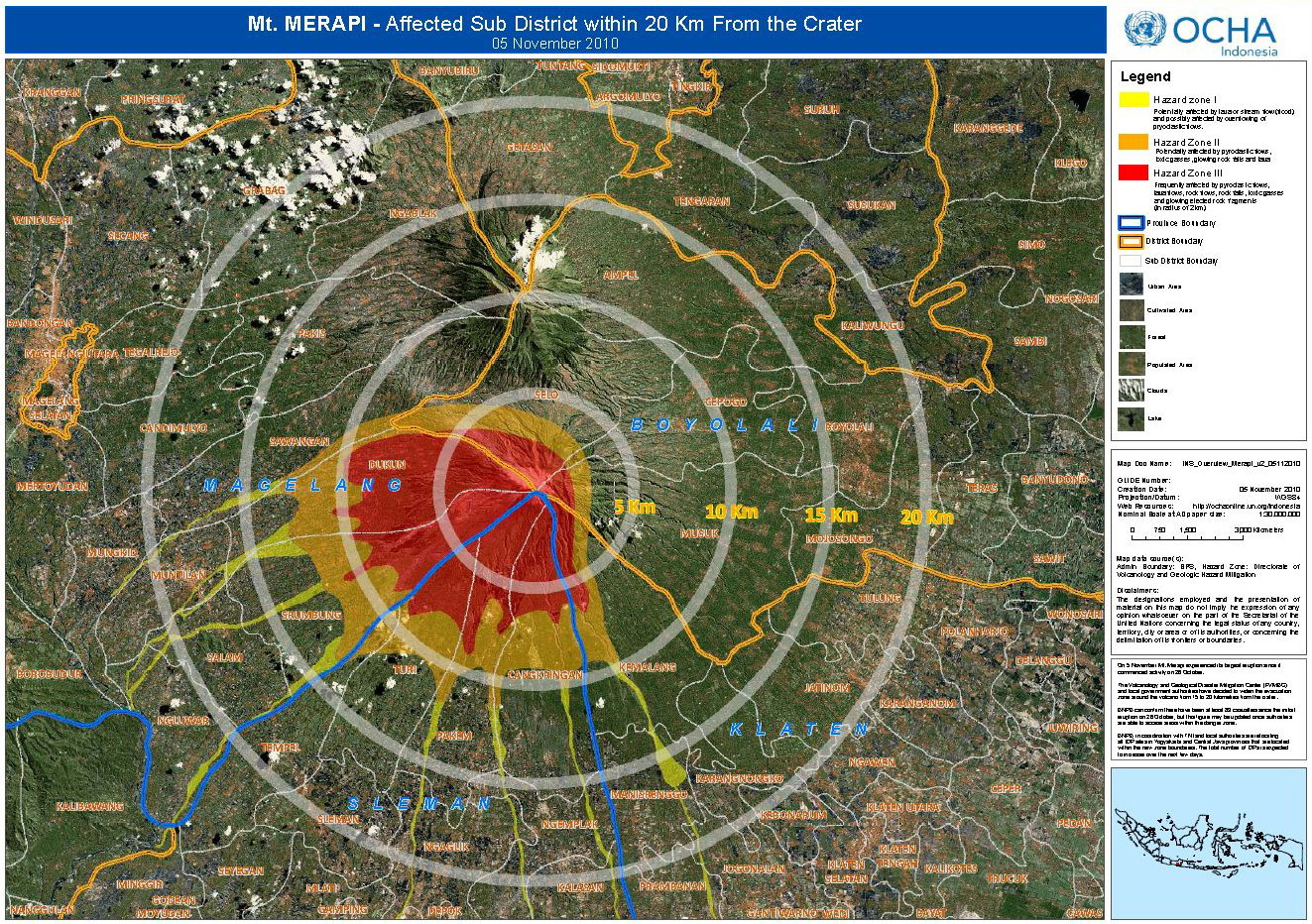

The most recent explosion at midnight on 5 November nearly doubled the number of deaths linked to the eruption, the extent of the no-go zone surrounding the mountain, as well as the number of people displaced.

The evacuation zone expanded from 10km around the summit on 25 October to 15km on 3 November to the current 20km.

“Everyone is an expert when a volcano erupts and I do not want to be swayed by criticism in the media,” government volcanologist Surono, who like many Indonesians uses a single name, told IRIN from Yogyakarta, about 30km form Merapi. Yogyakarta is where government disaster officials, regional medical staff, dozens of NGOs and 250 rescue workers are monitoring the volcano.

Below are parameters Surono considers before issuing volcano alerts:

Seismic energy: Excess energy of a volcano is measured through ground motion detection sensors (seismometers) placed throughout Merapi, which transmit continuous real-time data to five field posts near the summit. These readings are transferred to a central tower in Yogyakarta 30km away, which is now the only observatory frequented by scientists after the most recent evacuation. Like a heart-monitor reading, wave amplitude indicates motion. Readings broke 800cm – almost twice the level during three previous eruptions – when Surono upgraded the advisory level on the volcano to the highest level four on 25 October to indicate that an eruption was imminent or under way. Increased seismic activity is one sign of increased likelihood of eruption.

Chemical analysis: As magma – a mixture of liquid rock, crystals, and dissolved gas – nears the surface of a mountain and its pressure decreases, gases escape. Increasing levels of sulphur dioxide and the water level of released gases are other signs of the imminent arrival of magma – and a potentially explosive eruption.

|

Photo: Surono  |

| Head of Indonesia's volcano disaster alert centre, Surono |

Ground deformation: Reflectors mounted at the mountain’s summit use electric distance measurement and tools to measure the Earth’s tilt to assess how the ground swells, which is one sign of how lava mounts. This “inflation rate” indicates the intensity and speed of pressure build-up.

Socio-economic context: After the 5 November eruption, which caught villagers outside the original 10km danger zone unawares and destroyed two villages in the hard-hit Cangkringan area where rescuers are still looking for bodies, criticism mounted that there should have been a 20km danger demarcation from the first signs of volcanic trouble rather than only 10km. Surono, however, defended the gradual expansion: “Yogyakarta is the country’s second-leading tourist destination [after Bali]. We have tourists from around the world and many students studying here. A 20km evacuation too early would kill the economy and cause widespread panic.”

Psychological impact: “Panic kills, not ash and small rocks,” said Surono. Mountain dwellers have been hearing explosive sounds due to the larger-than-usual amount of molten rock stored in magma chambers. In past eruptions, most recently in 2006, there was only one underground pool of magma versus two now. “Widespread panic and fear can be as deadly as physical elements of the volcano and are equal considerations,” he added.

When asked when he might shrink the danger zone, allowing residents camped throughout the city to return home, including more than 30,000 people living in a large sports stadium near the closed Yogyakarta airport, Surono replied that only time and science would determine when he would issue the alert. “I am a geologist, not a mystic. We are in a marathon [of volcano monitoring], not a sprint.”

pt/ds/mw

This article was produced by IRIN News while it was part of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Please send queries on copyright or liability to the UN. For more information: https://shop.un.org/rights-permissions